By Len St-Aubin

IN THE GUISE OF “broadcasting policy”, Bill C-10, An Act to Amend the Broadcasting Act, is really about promoting Canadian content in online media. To do that, it would expand the Broadcasting Act to capture virtually all online (internet) audio and video.

My previous articles discussed how Bill C-10 and Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault’s forecast Cancon contributions risk highly problematic outcomes for Canadian broadcasting, for the internet in Canada and for Canadians. A third proposed an alternative approach.

This article returns to the impact on private sector television and revisits potential outcomes in light of market forces, Bill C-10’s incentives, and more realistic Cancon forecasts. As one industry insider told me “everyone knows [Heritage’s] numbers make no sense”.

Bill C-10 could severely undermine private sector broadcasting in Canada, and without any apparent vision or plan for what’s to come, including inevitable legal challenges.

The Broadcasting Act is grounded in a closed, domestic, system

From TV’s beginnings, the popularity of U.S. entertainment content, combined with a protected market, has made it cheaper, less risky, and more profitable for Canada’s private sector broadcasters to buy foreign than to finance their own original content.

So, a “regulatory bargain” was struck. Because broadcast distribution channels (over-the-air, cable, satellite) were domestic and finite, regulation could give priority to Canadian broadcasters, and restrict access to foreign. That protected broadcasters’ rights to popular foreign programs, securing their middleman business model. In return, broadcasters must, on average, spend 30% of annual gross revenues on Cancon. Over 65% of that goes to news, information and sports (CRTC data).

Along the same middleman model, the CRTC has licensed, and protected, Canadian “clones” of popular U.S. specialty channels. For example: Bell Media’s Discovery Canada acquires the rights for minority owner Discovery U.S. programming, adds on the required Cancon, and it’s a Canadian broadcaster.

Canadian independent producers are part of the bargain, too. From them, broadcasters must acquire most (75%) of their Cancon “obligation” for scripted fiction and documentaries (known as programs of national interest, or PNI). Independent producers get tax credits and other public financing to help them produce, own, and monetize PNI. Broadcasters don’t — but subsidized supply feeds regulated demand.

As change accelerates, Bill C-10 offers rear-view-mirror vision

Today’s broadband internet enables global direct-to-consumer audio and video distribution. That makes local broadcaster middlemen unnecessary – and exclusive, original content a more valued competitive advantage.

Internet-native streamers like Netflix pivoted immediately to direct-to-consumer, on-demand distribution. Why would CBS, NBC, ABC, Disney, Discovery, etc. continue to sell their valuable content to foreign local middlemen if they don’t have to? Some are figuring that out. Disney+ and CBS All Access (soon to be Paramount+) are in Canada — with premium content not available to our broadcasters.

“In response to this radically different market, Bill C-10 would reflexively apply the same old policy online.”

In response to this radically different market, Bill C-10 would reflexively apply the same old policy online: Imposing the same Cancon obligations on global streamers and Canadian broadcasters alike. Yet, only foreign streamers that have a business presence or large subscriber base in Canada would have reason to comply. Others could simply block Canadians’ access, or test CRTC enforcement. Those with a reason to comply would, as discussed below, also have leverage to negotiate.

For their part, Canadian broadcasters have been lobbying for reduced regulation to help them compete, but Bill C-10’s suite of new regulatory powers foreshadows the opposite outcome. They’ve also asked for access to public financing so they, too, can migrate to more original content they can own and monetize, rather than spending all of it with independent producers. On that, the government has been silent.

Still, broadcasters and independent producers support Bill C-10’s promise of return to the status quo ante — however unlikely that outcome. It’s unclear from the bill, or its accompanying briefing materials, whether the government has contemplated what comes next.

Even Bill C-10 couldn’t sustain the middleman business model

Canada’s major broadcasters are owned by, or share owners with, vertically-integrated telecommunications and media conglomerates (BCE, Quebecor, Rogers, Shaw/Corus). Those conglomerates’ shareholder value derives from cash-flow-rich, profitable, wireless and internet (formerly telecoms) businesses. However, the creative, high-risk, high-cost, original scripted content business isn’t the best fit — especially since broadcasters can’t access public financing needed to own and make money from it. The online middleman business like BCE’s Crave, well, maybe that’s it.

That pretty much depends, however, on Minister Guilbeault’s forecasts that Bill C-10 would impose Cancon obligations of 25% to 45% of gross revenues in Canada from foreign streamers. That, combined with Bill C-10’s heavy-handed regulatory powers, would constrain market entry and possibly precipitate exits. To the extent that happened, blocked content would enable, even incentivize, Canadian broadcasters to buy foreign over investing in Cancon originals.

The major broadcasters have so far secured multi-year foreign content deals and Bill C-10 seems to suit them just fine. The trouble is, it’s unsustainable. First, those forecasts are unlikely.

Second, Canadians have been bypassing broadcasting policy for decades, and the internet is not a closed-access cable-TV system. Online, VPNs would flourish. Taking Canadians to court to stop VPNs, and/or piracy — as work-arounds to artificially-constrained choice — would be unpopular and tough for government. It would be left to broadcasters and the CRTC, and become a costly, futile, game of whack-a-mole.

So what would foreign streamers’ compliance with Bill C-10 look like?

In return for compliance, global streamers would have leverage to negotiate down the Minister’s Cancon expectations and regulatory burden. Working in their favour are popularity, hundreds of thousands of satisfied subscribers, very significant investment in Canada’s production sector (meaning jobs and economic impact), Cancon export opportunities, and the ability to block access.

As well, previous articles have shown that the forecast Cancon contributions risk trade retaliation and negative impact on Cancon policies intended to foster Canadian ownership of intellectual property. Somewhere between 5% and 7.5% (definitely not 30%) would be a more likely outcome. Even at that level, though, required investment in Cancon would only reinforce global streamers’ already significant competitive advantage against Canadian broadcasters.

Streamers want global content — it’s what they do. In 2020 Netflix alone spent US$17.3 billion on video content. If streamers must invest in Cancon, it would probably be very good.

“Bill C-10 could effectively outsource the best, most culturally-sensitive, subsidized, Cancon to foreign streamers — and Canadian audiences would follow.”

By contrast, “PNI” has been an obligation for broadcasters — a burden. A tax. Market forces, regulation, and Cancon financing policies leave them little incentive to invest in, own, and monetize high-risk scripted fiction and documentaries. Beyond news and sports, less costly “lifestyle” content (cooking and home reno shows, etc.) that they can own and monetize has become a focus.

To be fair, they have helped finance some excellent Cancon like Cardinal, Letterkenny, Departure, and a lot of children’s shows. Still, it’s considered an expense — not an investment. They’ve told the CRTC that they want their PNI spend — just 7.5% of gross revenues, or $426 million in 2018 — reduced.

Global streamers could easily outbid broadcasters for the best Canadian stories, creators, casts, crews, and facilities. Working with independent producers, they would benefit indirectly from rich Cancon tax credits, Canada Media Fund financing, and subsidies, too. Bill C-10 could effectively outsource the best, most culturally-sensitive, subsidized, Cancon to foreign streamers — and Canadian audiences would follow.

That would significantly change Canadian broadcasting. Regulation has meant Canadians watch their favourite foreign shows on Canadian channels where they might watch Cancon too. Under Bill C-10, Canadians could end up watching both their favourite foreign and Canadian shows, on foreign streamers.

Streamers and content providers are likely weighing options

If a mandated 5% to 7.5% spend of gross revenues on Cancon is the more likely outcome, then global streamers would have viable alternatives. They could:

- nonetheless block Canadians’ access, and sell their content to broadcasters;

- comply, offer minimal Cancon, and make two-tier content deals with broadcasters (some already do the latter); or

- wait-out the inevitable legal challenges (more on that later).

This may explain why the Motion Picture Association (MPA) Canada has been silent.

The MPA represents major U.S. studio/broadcaster/streamers including: Disney/ABC, Paramount, Sony, Universal/NBC, Warner Brothers, and Netflix. Except for Netflix, neither the MPA, nor its members, have publicly said much of anything throughout the three-year public process leading up to Bill C-10, or about Bill C-10. The association has, however, started promoting how much they spend in Canada.

Internet-native Netflix has already positioned itself as a provider of diverse, original, international content from many cultures and languages — including “certified” Cancon.

For others, Canadian content obligations could be more of a stretch. However, they have ongoing relationships in Canadian broadcasting as content providers to conventional networks and specialty “clones”, and/or as foreign services authorized for distribution by broadcast distributors. Whatever the outcome, there’s something in it for them.

Disney+ just launched its new Star streaming channel in Canada. Greg Mason, Walt Disney Studios Canada, told Cartt.ca “We’ve got great partnerships with Bell, Rogers and Corus. We do so much with them on so many different levels and we’ll continue to do that, but it’ll become more apparent we’re going to have Star originals that are not going to be anywhere else.” So, broadcasters get some content, global streamers keep the premium.

Compliance with Bill C-10 could mean the collapse of the “clones”

Canadian specialty channels which rely heavily on foreign content — whether or not they share branding with U.S. counterparts — are an artefact of regulation that kept out foreign broadcasters. Bill C-10 would remove that protection.

All video content, and sooner or later all broadcasters, are moving online. Under Bill C-10 foreign online undertakings could register with the CRTC and serve Canadians directly, subject to Cancon obligations. That’s a game-changer. Never before has the Broadcasting Act provided for that.

“It’s one thing to protect Canadian licensees on finite-capacity broadcasting distribution systems. It’s quite another to keep out foreign online services offering to comply with Cancon requirements if Bill C-10 allows them in.”

So as contracts with broadcasters expire, foreign content suppliers could shift that content to their CRTC-registered online undertakings if they already exist, or apply for registration with the minimum Cancon commitment (at 5% to 7.5% of GR, that’s a viable option). Canadian independent producers already have established Cancon supply chains with the clones that would be supplanted, and with U.S. counterparts.

Is that a plan? Who knows? But if Bill C-10 passes, it’s not clear how the CRTC could refuse. It’s one thing to protect Canadian licensees on finite-capacity broadcasting distribution systems. It’s quite another to keep out foreign online services offering to comply with Cancon requirements if Bill C-10 allows them in.

Expect broadcasters to seek removal of Canadian ownership rules (a.k.a. foreign investment restrictions).

Before any of that, expect legal challenges

Broadcasting didn’t exist in 1867 of course, so it’s not in the Constitution. The courts had to determine whether it was a federal or provincial responsibility.

Starting in 1932, a string of court decisions concluded that radio frequencies — like telegraphy, posts, railroads, and telecommunications — cross provincial and national boundaries, so that makes radio and TV broadcasting a federal responsibility. Cable TV systems receive and retransmit those radio frequencies, so they’re federal too.

Beyond radio frequencies, the Broadcasting Act asserts a national interest claim that “the Canadian broadcasting system… provides… a public service essential to the maintenance and enhancement of national identity and cultural sovereignty.” That claim had more merit when broadcasters operated over a finite number of channels.

But here’s the thing: Never have the courts determined that an audio or video content service, delivered by telecommunications but that does not itself use radio frequencies, is a broadcaster under federal jurisdiction. Untethered from radio frequencies, federal jurisdiction is, well, to be determined.

Yet Bill C-10 would capture, as “broadcasting” online audio and video services that make no use of radio frequencies, are not distributed by broadcast distribution systems, and make content available at the request of end users as on-demand transactions – with each end-user in full control to initiate, rewind, fast forward, pause and terminate. That would capture global streamers, but also the Ottawa Public Library streaming video, for example.

Arguably, online audio and video are more like retail than broadcasting.

Given Bill C-10’s overreach and necessarily selective CRTC licensing, registration and exemption, litigation seems inevitable. That would highlight jurisdictional uncertainty and like other litigation about broadcasting jurisdiction, it would end at the Supreme Court.

A reference from the government to the Supreme Court to clarify jurisdiction — a well-established practice — would have saved much time and money for everyone, including the government and Canadians. But, Bill C-10 is now in Parliament.

Suffice to say the notion Bill C-10 would be quickly implemented is wishful thinking. CRTC implementation would be mired in challenges, uncertainty and delay that would take years — not nine months, as the minister has promised.

A more market-oriented approach is needed

As the challenges proceed, streaming will carry on, along with all the issues and problems identified over five years of consultations. Broadcasters’ revenues will continue to decline as they gradually lose access to the most popular foreign content and Canadians shave and cut the cord. With little incentive to invest in, own and monetize original scripted fiction and documentaries, that alternative revenue stream, and competitive advantage, looks unlikely.

Who, in the end, will cover local news, politics and sports?

As broadcasters call for less regulation — in response to the greatest selection of audio and video content that Canadians have ever been able to acce ss — group after group is appearing before the House of Commons Heritage Committee asking for more recognition, codes for this, terms for that. All meaning more, not less, regulation.

ss — group after group is appearing before the House of Commons Heritage Committee asking for more recognition, codes for this, terms for that. All meaning more, not less, regulation.

A more market-oriented approach could achieve better outcomes and be implemented more quickly than anything under Bill C-10.

Some of the changes discussed in this article are inevitable, but rather than setting-up Canadian broadcasters to compete, Bill C-10 risks setting them up to fail.

Consultant Len St-Aubin (right) concluded his most recent client commitment as of 31 Dec. 2020. The views expressed in this opinion are his alone. Formerly he was Director General, Telecommunications Policy, at Industry Canada, he was also a member of the policy teams that developed both the 1991 Broadcasting Act and the 1993 Telecommunications Act.

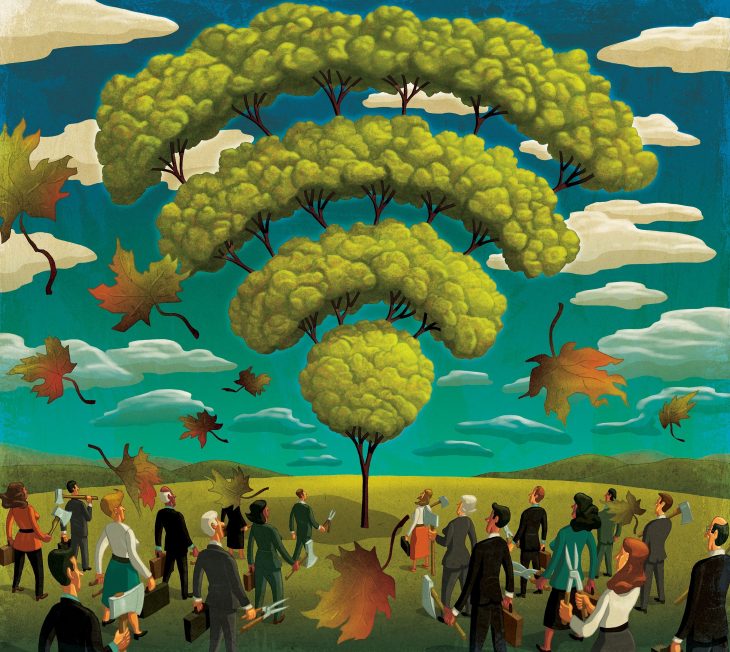

Original artwork by Paul Lachine, Chatham, Ont.