By Howard Law

HERITAGE MINISTER PABLO RODRIGUEZ has promised a policy directive to the CRTC with cabinet instructions on implementing Bill C-11.

Point number one in the new directive should be making the certification of Canadian content more relevant to the Canadian experience by including qualitative judgments of national subject matter in the video content. I posted about this recently, as have others. The signal from the minister is that he has an open mind to it.

Point number two is to direct the CRTC to reappraise the existing regulatory supports for the money-losing local news industry.

Point number three is what to do about “programming” that is user-generated content (UGC) uploaded to hosting platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Facebook.

So far it seems as if the debate about UGC —in blogs, tweets and witness appearances before the Heritage Committee — has been binary: UGC is entirely in or out of the act.

UGC appears in Bill C-11 not because the government seeks the power to police its content. That may indeed become an issue someday if the government tables an Online Harms Bill. But as I posted earlier, C-11 is drafted to shut the door on supervising the content of UGC.

UGC is in the bill because hosting platforms like YouTube act as broadcasters even though they are direct-to-consumer platforms for media creators, quite different from content-curating broadcasters Bell Media, Rogers, TVA, Netflix, or Disney Plus.

The government wants the hosting platforms to share the responsibility of creating and distributing Canadian content and that means adapting CanCon regulation to a new business model where programming consists of un-curated uploads.

Conservative MPs and other critics of C-11 seem to be grudgingly (and tactically?) conceding that Netflix and the other large American streaming platforms might be appropriately covered by the new Broadcasting Act so they can begin carrying their fair share of the burden of creating and distributing Canadian content. But those same MPs and critics made it clear during this week’s Heritage hearing they remain opposed to regulating YouTube and other hosting platforms.

Alas the debate over UGC is in danger of becoming a dialogue of the deaf.

On one hand C-11 makes it clear that UGC programming will only have a regulatory impact if it is sufficiently commercial in nature, triggering the hosting platform’s obligations to contribute cash to Canadian media funds and promote Canadian content channels in its viewer recommendations.

On the other hand C-11 opponents want no part of even that limited regulatory activity, fearful of mandatory CanCon recommendations alienating the global audience for Canadian creators. Open Media’s Matt Hatfield went so far as to disparage the Broadcasting Act’s rules on pushing Canadian content as “parochial.” All of this is despite the fact that the Liberals announced in the House back on March 30th they would not regulate programming uploaded by “digital first creators.”

Amidst the polemical noise, Toronto Metropolitan University professor Irene Berkowitz appeared before the Heritage Committee to focus on how the creation and distribution of content by Canadian digital creators actually works.

Berkowitz published her study of the YouTube broadcasting platform “Watchtime Canada” in 2019. Of course it’s out of date now but remains an essential drill down into how broadcasting on the hosting platform works as a business model. The report was commissioned and paid for by YouTube, and Berkowitz is categorically opposed to regulating the hosting platform, but allowing for her point of view it provides a good survey of the landscape to Heritage MPs.

Here are a few things on that landscape:

YouTube is a hybrid of different online platforms including:

- A flanker streaming platform for well established broadcasters and studios to add to their existing distribution in radio, TV, and online. Think Rogers Sportsnet or CBC News.

- A platform for branded multi-channel aggregators that behave a lot like conventional broadcasters.

- A free or premium music service that competes directly with legacy and other online music services.

- An archive of classic video content, I am guessing most of it in the public domain and not copyrighted.

- A free direct-to-consumer broadcasting platform for successful independent artists and small creative companies who are delighted to end-run Canadian media curators and make money by splitting adverting revenue with YouTube on a 55/45 split once they surpass the minimum audience threshold.

- For 75% of uploaders, a free direct-to-consumer platform for up and comers, hobbyists, and struggling artists who hope one day to make money on the platform.

- And for consumers it must be added: a treasure trove of DIY videos.

The entrepreneurial lustre of YouTube is a free platform with a potential global market (Berkowitz provides data on the major export markets in the US and the UK, with the Indian and French markets still a work in progress as of 2019). Unlike the curated broadcasting industry, YouTube creators don’t have to sell their copyright to broadcasters and studios to reach an audience.

So what part of YouTube is a candidate for regulatory obligations supporting the creation and distribution of Canadian news, sports and entertainment?

YouTube’s UGC programming that is the most highly analogous to regulated broadcasting is the video content on flanker streaming platforms and multi-channel aggregators, as well as audio content on music services. That programming is monetized by advertising revenue captured from the rest of the Canadian media universe (and subscriber revenue in the case of the premium music service). It’s hard to appreciate an argument that this programming should not generate regulatory obligations for YouTube.

But it gets complicated after that when we consider the YouTube ecosystem of digital first creators.

First, there is the argument that discoverability — obliging YouTube to push Canadian content— could backfire on independent artists and small businesses seeking the global market. I remain to be convinced this is a real danger, but it’s not something we want to make a mistake on.

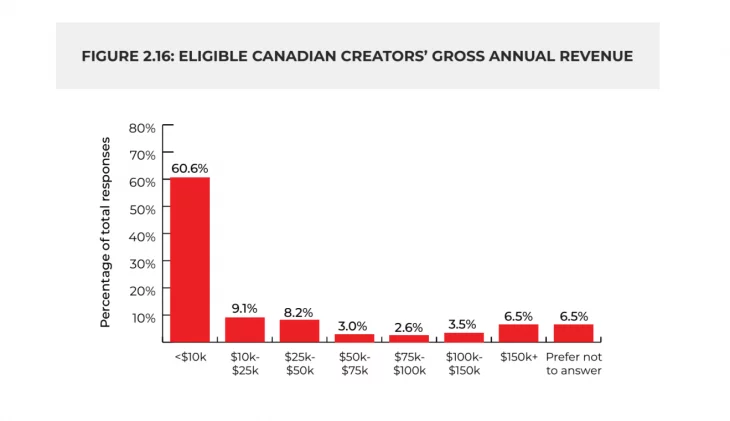

Second, as of 2019 there were 160,000 Canadian creator channels (of which 40,000 were monetized and about 15,000 belonged to artists and small enterprises making real money at it). They generate thousands of video posts. How badly do we want to expend civil servant time viewing and certifying them as Canadian content? (Please see chart above, borrowed from the Watchtime report, for information on distribution of earnings among the 40,000 monetized channels.)

Third, if the programming from these digital first creators were to be counted towards YouTube’s financial responsibility to contribute to Canadian media production funds, how are we going to deal with the possibility that YouTube would pass along those costs to the creators by changing the 55/45 advertising split?

Maybe all of these challenges are surmountable, but the CRTC may well look at it and decide that the regulatory squeeze in not worth the juice.

So here are my instructions to the CRTC:

- Divide YouTube programming into major categories of commercial activity, keeping an eye on the size of the media business sponsoring the channel, its success in monetizing content, and whether it seeks audiences in the CRTC’s categories of priority Canadian content (i.e. news, drama, sports, music, entertainment.)

- Regulate the programming uploaded by corporate channels in those priority areas which means YouTube as the host platform must make financial contributions based on the value of that programming and promote certified Canadian content through recommendations or keyword search results.

- Exempt everyone else until and unless circumstances change.

A footnote on discoverability of Canadian content from Watchtime 2019:

Professor Berkowitz makes the point in her study that YouTube is a global media platform, unlike the domestic distribution of conventional Canadian media, and as such caters to Canadian viewers seeking that global content.

With an eye to the debate on mandated discoverability obligations, Berkowitz asked a series of questions to her 1,200 survey viewer participants. Survey questions are notoriously blunt instruments given their brevity, but here are three interesting questions and outcomes:

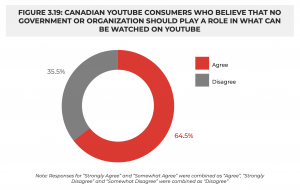

- Is regulation of what viewers can view good or bad?:

Given that the question can easily be interpreted as soliciting views on censorship (as opposed to discoverability), the results are not surprising.

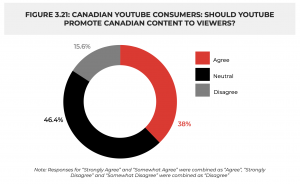

- Is promotion of Canadian content on YouTube a good thing?

A high rate of indifference to this question, but far more positive than negative.

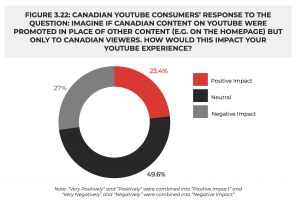

- What if promotion of Canadian content hides other content?

Even when you phrase that question as a zero sum proposition — promoting one kind of content means less of another — the conclusion is mixed and begs further survey questions.

Howard Law was the director of Unifor’s local media unions from 2013-2021. He now blogs at mediapolicy.ca, where this article first appeared.