WINNIPEG – Local TV – the place where many Canadians turn to for news about their community and country – may cease to exist inside of a decade, thanks to the unending growth and development of technology and the opportunities and challenges that development fosters.

A new discussion paper from Winnipeg consultancy Communications Management Inc. entitled Canada's Digital Divides paints a grim picture of the near future of both local TV and newspapers – and tries to make sense of what that means for journalism and democracy. Ubiquitous broadband, argues the paper “continues to enhance news-gathering and distribution, but it overwhelms and disrupts the old economic model on which traditional media have depended.

“And while the spread of broadband connectivity should clearly be a national priority, the impacts on established media, and on our ability to continue to support everything from local journalism to high-quality Canadian television drama, should also have high priority as a parallel concern of public and private policy.”

The paper goes on to predict the demise of all printed newspapers come 2025 and says there may also be no local conventional broadcast stations left by then either. Oh, people will watch television, but it will look “less like broadcasting, and more like e-commerce for programs” as Canadians look to access shows over-the-top, via their broadband connections only. “That evolution has not only changed the terms we use to describe television, but it has also changed the balance of revenue sources and delivery methods within the television system,” reads the paper.

A bundle has long been a staple of media. Newspapers bundled all sorts of stories and sections into one package for sale. Local broadcasters have traditionally done the same with entertainment, news, sports, kids, community service broadcasting and other genres where the profitable shows supported the not profitable, but still necessary, programming.

As specialty channels grew over the past 20 years, however, “local stations lost their ability to internally cross-subsidize from profitable to unprofitable genres,” says the report, and local TV’s profitability shrank markedly. And now with so many additional viewing options available via broadband, OTA stations are seeing their revenue drop off dramatically as advertisers shift to other platforms.

“(I)n 1995, private conventional television was the largest component in the Canadian television programming system, and accounted for almost 50 per cent of the revenue of Canadian television programming services. By 2014, among Canadian TV programming services, private conventional television’s share was down to less than 25 per cent, with specialty services holding the largest share,” says the paper.

“Canadian private conventional television now has revenue lower than it was in the late 1990s, and a revenue market share that has fallen, in 20 years, from almost 50% to just over 20%.”

“Canadian private conventional television now has revenue lower than it was in the late 1990s, and a revenue market share that has fallen, in 20 years, from almost 50 per cent to just over 20 per cent.” However, as most viewing shifts to the Internet and viewers enjoy unprecedented flexibility and variety, the “industrial organization” of making, distributing and paying for those programs is breaking down, putting the entire system under enormous strain.

And, what of the journalism being done by broadcasters if local TV goes away entirely, asks the paper’s authors? “We estimate that printed daily newspapers and private conventional television are the two largest spenders on journalism in Canada today, followed by specialty TV channels (as a group), and CBC/Radio-Canada conventional television,” reads the paper.

“If the two largest sources of spending on journalism in Canada today might be gone or much diminished in 2025, what will take their place… what will happen to local journalism?

“Will we get our news from Apple, Google, or Facebook? Without the current scope of journalistic output, where will Apple, Google and Facebook get their news? And, of course, there are numerous online-only start-ups, often specialized in nature, but few, if any, provide the kind of journalistic scope of our current local daily newspapers or local broadcast television.”

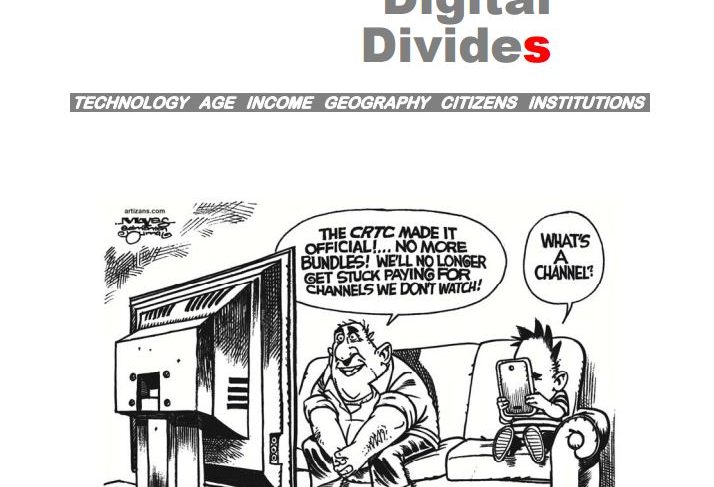

With the impending breakup of the channel bundles coming in 2016 thanks to the CRTC’s new a-la-carte policies developed during its Let’s Talk TV process, that measure is just a transitional stage to the future where people will want to just pay-per-program. That, too, will dramatically impact the amount of money available to local broadcasters for journalism.

“By 2025, we believe that the building block of the television business model will be the program, not the channel.”

“By 2025, we believe that the building block of the television business model will be the program, not the channel, and most of the transactional relationship between consumers and television will come to be regarded as ‘e-commerce for programs’, reads the paper. “There are already signs that we are moving in this direction. Consumers are increasingly recording programs on video recorders, or adding channels to packages based on signature or marquee programs.”

Will Canadians pay for their local news shows? The paper doesn’t speculate on that.

As we make the transition from the current bundled model to a show-focused TV industry, discoverability for those many thousands of shows remains a conundrum, says the paper. The CRTC plans a discoverability summit some time this fall and hopefully, the work on that – which is a huge challenge everywhere, not just Canada – will be solved by more technology.

“To the extent that BDUs or other suppliers of video programming start to look more like online ‘stores’, then the mechanisms for discovery and the mechanisms for choosing/purchasing the programs may become more closely integrated,” reads the paper. “Thus, we could have two general types of discovery – guides to programming that are independent of the online ‘stores’, and guides to programming that are part of an Interface that combines finding, describing, rating, and purchasing the programs we will watch.”

The CMI paper also delves deeply into broadband adoption and mobile adoption rates, breaking it down for income, age and area of residence and it found that yes, a significant chunk of the households led by the under-30 set (25%) are either cord-cutters or cord-nevers – meaning they likely never see local TV unless they have rabbit ears – and that by the end of 2015 there will be more than a million Canadians who subscribe to cable, but only for the broadband connection.

So with all this fragmentation, all these digital divides and the impact on journalism, what happens to shared experiences, and mutual interests that can bind a nation?

Or, asks the paper in its conclusion: “How will a modern democracy function if we all have less in common?”

Click here to read the whole thing.