Today marks the 100th anniversary of broadcasting in Canada

By Ken Goldstein

MAY 20, 1920, 100 YEARS AGO TODAY, was warm in Ottawa, with the temperature reaching 24C. That evening, at the Chateau Laurier Hotel, there was a meeting of the Royal Society of Canada, including a demonstration involving new communications technology – “wireless telephony”, as it was then called.

The audience at the Chateau Laurier included Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden and Opposition Leader W.L. Mackenzie King. They heard a program of spoken word and live and recorded musical content that was broadcast from XWA, the Marconi-owned facility in Montreal.

By 1920, “wireless” had been in various stages of experimentation for a couple of decades, but the XWA program that evening marked an important transition into the concept of broadcasting.

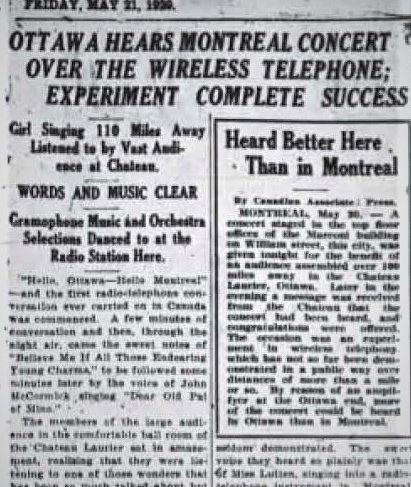

The Ottawa Journal was one of many papers that reported on the first broadcast.

In fact, it might have been the world’s first real, scheduled, radio program. That “first” has often been claimed for KDKA, in Pittsburgh, with its broadcast of U.S. election results in November 1920. But the Montreal-to-Ottawa broadcast preceded that by about six months.

Even without claiming a “world record”, it appears that the broadcast heard in Ottawa on the evening of May 20, 1920 was the first scheduled radio program in Canada.

So today – May 20, 2020 – is the 100th anniversary of Canadian broadcasting.

It’s a good time to celebrate the industry and its accomplishments, and also to reflect on how that first broadcast helped to set in motion the events that shaped the industry we know today.

The day after that 1920 broadcast, newspapers across Canada reported on the event. According to broadcasting historian Mary Vipond in her 1992 book Listening In: the first decade of Canadian broadcasting, “many Canadians first became aware of radio broadcasting through reading press reports of this remarkable concert.”

Radio captured the imagination of individual Canadians in all parts of the country. It also caught the attention of governments and business – most of which were unsure where this new technology would lead.

Across Canada, young people were motivated to start building crystal sets, in the hope of picking up distant radio signals. Many years later, an article in the February 25, 1966 issue of LIFE magazine referred to Winnipeg in 1921, where 10-year-old Marshall McLuhan “started making crystal sets for his friends, neighbours and parents”.

And the article quoted McLuhan about those early days of radio: “Probably the biggest thrill of my life was sitting there in Winnipeg picking up station KDKA in Pittsburgh.”

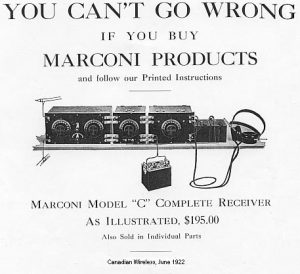

Of course, not everyone built or bought a homemade crystal set. You could also buy a branded receiver, as indicated in the advertisement reproduced here from the June 1922 issue of Canadian Wireless (published by Marconi).

By the end of 1922, XWA in Montreal had become CFCF, and a number of commercial radio stations had been licensed across Canada (CFCF-AM was shuttered by then-owner Corus in 2010).

“A number of Canadian newspapers were early owners of radio stations, driven by a mixture of motivations, including a desire to broaden their communications reach.”

But, while radio was exciting in 1922, much of its potential future impact was still a mystery. A good example was an article that ran in the June 15, 1922 issue of Maclean’s magazine, with the headline: “What will radio do to us?” The article reviewed a number of prophecies for the future of radio, but one paragraph captures the mood of the time:

“This is Modern Magic not only in its character but in the swiftness with which it has caught the popular fancy, and the almost unbelievable development that has come in so short a space in time.”

A number of Canadian newspapers were early owners of radio stations, driven by a mixture of motivations, including a desire to broaden their communications reach, and a concern that radio would become a competitor for advertising. (And later, the unrealized idea that radio would deliver newspapers to individual households via facsimile.)

The telephone companies were also interested, motivated by the potential inherent in the description of radio as “wireless telephony”. And that led to one of the most interesting “what ifs” in the history of Canadian broadcasting.

This advertisement appeared in the June 1922 issue of Canadian Wireless magazine. Note the price for the Marconi radio receiver – $195. Adjusted for inflation, $195 in 1922 dollars would be equivalent to about $2,900 today. Thus, for the equivalent amount that a radio alone might have cost in 1922, Canadians today can purchase more than one radio, plus a TV set, plus a smartphone, plus a personal computer, etc., etc. – another example of the long-term downward trajectory in the cost of consumer electronics.

In 1922, the two Winnipeg daily newspapers, the Free Press and the Tribune, had each established radio stations. By 1923, however, the experiments were not going well. At the same time, the Manitoba Telephone System (a provincial crown corporation) was interested in radio, in part because it saw radio as a potential competitor.

The two daily newspapers agreed to vacate the field, and the telephone system established a new radio station in Winnipeg, CKY. To make that happen, the governments of Manitoba and Canada negotiated a deal in 1923 under which the provincial telephone system would receive 50 per cent of the radio receiver licence fees collected in Manitoba, and would have what amounted to a veto over any other radio station licences in the province.

So the first public broadcaster in Canada was, in fact, the Manitoba Telephone System. The head of the provincial telephone system at the time was John E. Lowry, and it can be argued that, by exercising the powers in the agreement between Canada and Manitoba, he was, in fact, Canada’s first regulator of broadcasting. (The veto power was used in 1927 to deny a private radio licence application for Brandon.)

And here is the interesting historical footnote – in 1923, the federal government had indicated its willingness to make similar licence fee sharing arrangements with stations in other provinces, but none of them took Ottawa up on the offer. One can only speculate on how broadcasting in Canada might have developed differently if other provinces – particularly Quebec and/or Ontario – would have acted on the federal government’s willingness to share some of its jurisdiction at that time.

Federal broadcasting policy drifted through the middle of the 1920s, until 1928, when the federal government appointed the Aird Royal Commission to look into the future of broadcasting in Canada. The commission reported in 1929, and recommended a public system.

That set off intense debate, partly over public vs. private, and partly over federal vs. provincial jurisdiction.

“So, roughly 10 years after that first broadcast 100 years ago, the fundamental magnetic poles of the debate over Canadian broadcasting were set in place – and they have been influencing the debate ever since.”

A sense of the public vs. private debate can be found in two articles that ran, side-by-side, in Maclean’s magazine on May 1, 1930. The overall heading was: “Does Canada Want Government Radio?” The sub-head on the “NO” side stated: “Government control means political control and curtailed programmes for the listener-in”. And the sub-head on the “YES” side stated: “Government control of broadcasting is the only means by which we can prevent United States domination of the Canadian air”.

So, roughly 10 years after that first broadcast 100 years ago, the fundamental magnetic poles of the debate over Canadian broadcasting were set in place – and they have been influencing the debate ever since.

While the public policy debate was continuing, the jurisdictional dispute went from the Supreme Court of Canada to the Judicial Committee of the British Privy Council, which ruled, in February 1932, in favour of federal jurisdiction over broadcasting in Canada.

Prime Minister R.B. Bennett then proposed that an all-party committee be set up to examine the issue further. Since the jurisdictional issue had been resolved, the committee’s work might be characterized as examining two broad concepts – federal regulation of private broadcasting, or a federally-owned public system.

But the tipping point in the committee’s review appears to have involved something else – an attempt to guess how broadcasting technology would shape its economics.

On April 20, 1932, the committee heard from Edward W. Beatty, the president of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Beatty argued for private ownership with government regulation. Beatty’s appearance before the committee was covered in The Globe on April 21, 1932, which reported on an exchange between Beatty and E.J. Garland, the United Farmers of Alberta MP for Bow River, Alberta: “[Beatty] admitted to Mr. Garland that radio was a natural monopoly.”

While it was not the only reason the government decided to create a public broadcaster, it is a fact that many of the decision-makers of the day saw the essential policy option as a choice between public and private monopoly.

The House of Commons Special Committee on Radio Broadcasting reported in May 1932. That was followed by legislation to create the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission, which functioned from 1932 until 1936, when it was replaced by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

The irony, of course, is that radio never was a “natural monopoly” – so one of the early underpinnings of Canadian broadcasting policy was influenced, at least in part, by an incorrect assumption about technology’s impact on economics.

Something to consider, perhaps, starting tomorrow – the first day of the second century of Canadian broadcasting.

Ken Goldstein is president of Winnipeg-based Communications Management Inc.; he is a media economist and historian.