WITH LIMITED NETWORK RESOURCES and many competing demands by subscribers, applications, and content providers, satisfying the demands of one stakeholder means taking resources away from another.

This problem, along with the greedy nature of applications and the over-subscription model of the Internet challenges network operators and the regulatory environment as they strive to maintain Internet freedoms that subscribers expect from the industry.

What follows is a technical White Paper from Sandvine Inc.

Broadband service providers are thus in a position to ensure network neutrality with the fair allocation of network resources between potentially competing uses of the network.

To do so, operators need tools that give them visibility into the traffic that traverses their network and control the allocation of resources between subscribers, applications, and content providers to derive maximum utility from the network. Subscriber Internet freedoms can then be realized by protecting the network and overall subscriber experience.

Should broadband network operators be legally bound to treat all services that move across their network the same way – not blocking any competing service or boosting their own offerings? The regulatory environment has been uncertain to this date, but the American Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is now grappling with how much and to what extent regulation should be used to shape the future of the broadband experience in the U.S.

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) are expressing similar sentiments to the issue in Canada. A clear vision for the future has been expressed by outgoing FCC chairman Michael K. Powell and embodied into the four “Internet Freedoms” that broadband subscribers should expect from the industry at large:

1. Freedom to access legal content

2. Freedom to use the applications of their choice

3. Freedom to use the appliance or device of their choice

4. Freedom to obtain service plan information

This position paper will explore the positive and negative implications these freedoms have for network operators and the responsibilities network operators will have to bear in order to support them.

Stakeholders in the Net

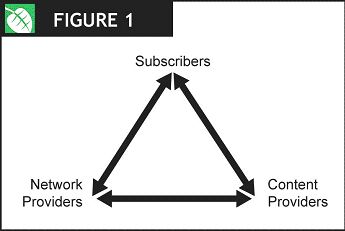

The Internet and access to it has become the foundation for the information economy, and as such, there are a number of different stakeholders with an interest in the behaviour of broadband networks. The major groups are subscribers, content providers and network providers or operators.

Figure 1: Co-dependence of broadband stakeholders.

A natural condition of codependence or symbiosis characterizes the way these groups interrelate. Network providers need happy subscribers who are willing and able to pay for network connectivity; content providers need subscribers to access their content and web sites in order to generate revenue, while subscribers want good network performance and access to compelling content. The entire ecosystem depends on balance – each pillar equally supporting the other to remain viable.

Issue 1: The Internet commons

The current situation in broadband is fast becoming a classic example of what economists call the “tragedy of the commons”. When too many owners are endowed with the privilege to use a given resource, the resource is prone to overuse and eventual depletion or destruction.

Individual subscribers are concerned about maximizing their own personal utility of the broadband service. There is no incentive for the subscriber to moderate their use of the network without some form of feedback via the service plan definition, cost, structure and enforcement.

Subscribers are not concerned, nor can they monitor how their consumption or use of the network is affecting other subscribers using the same network. With many subscribers paying for the same service, who is responsible to ensure that within a similar service tier, all subscribers have equal opportunity to extract value from their broadband connection? It can only be the network operator, the only entity with the required visibility to apply preferential allocation of network resources.

Issue 2: Content providers ride for free

A wide variety of online content enriches the broadband experience. Predicting what form this content will take, and how quickly it changes, is key to broadband growth.

Yet content providers overuse the Internet commons. All they want from networks is high performance and low latency for the subscribers who access their services. They are not concerned about how their utilization of network resources affects other content providers contending for the same shared resources. As such, they are network greedy and want more than their fair share of the broadband pie. Once again, the network operator is the only one in a position to provide some form of fair allocation of network resources between potentially competing uses of the network.

There is no fundamental issue with a network operator entering into a competitive offering for content or application services. If we accept the legitimacy of Internet Freedoms 1 – to access legal content, and 2 – to use the applications of their choice, the operator should not limit subscribers’ choice or use their position in the network to create artificial barriers for competing operators. It would appear easily argued that such tactics would be anti-competitive and run directly counter to freedoms 1 and 2.

Issue 3: Applications can be greedy

Broadband applications have been developed for an ever-increasing set of uses. From a network point of view, there is a wide spectrum of how resource-intensive these applications can be on the network.

Personal communication tools like email and instant messaging provide a high degree of value, yet they put a very light load on the network. Contrast this to live audio stream between players in a multi-player game session, where hundreds of kilobits per second (kbps) can be consumed per player. From an application point of view, the current king of network consumption is clearly the P2P file-sharing applications, often as much as 60% of total bandwidth consumed on the Internet. (Refer to Figure 2.)

Many of these streams or resource-intensive applications have been developed to adapt to the required capability of the end user’s broadband link. Interactive, multiplayer game audio systems will scale their audio codec to operate at optimal quality depending upon the network connectivity and capacity between the players. By default, these applications tend to train at the maximum possible rate in order to provide the highest quality of experience possible for the participants. This network training does not take into account how this increased use of network resources affects other applications or users of the network.

P2P file-sharing applications illustrate this ‘greedy’ training behaviour. BitTorrent clients will actively connect to as many other nodes in order to satisfy the users’ download request until the users’ access link capacity is saturated.

Figure 2: Protocol histogram by percentage bandwidth consumed.

The distributed applications are not motivated and lack the required visibility in order to provide a more fair allocation of network resources. It is the network operator’s role to provide the level of controls in the network that would attempt to reallocate network resources amongst all these applications according to some overall goal-maximizing function.

Issue 4: The net is over-subscribed

Over-subscription is a known part of any network and has been around since the dawn of telephony systems over a hundred years ago. It rests on the assumption, and statistical models derived from past subscriber usage patterns, that there will never be enough subscribers online at any given time to use up all available network resources. Network providers are thereby free to oversubscribe their networks up to the point of peak utilization.

For example, a 1 Mbps DSL or cable service does not guarantee 1 Mbps service to all subscribers, at all times, throughout the entire layer of the network. In the case of DSL, bandwidth is shared at the central office (CO) and in the case of cable, it is shared at the edge. The inability to guarantee sustainable bandwidth exists in both models but happens in different locations.

This over-subscription model is observed regularly in our modern life. For example, with water supply – everyone has experienced a hot-water scalding when another household member flushes the toilet. This is a graphic example of the water supply unable to fulfill the simultaneous demands of different users.

Over-subscription has a dramatic impact on the performance and applications in the network. It must be managed to increase overall utility of the network and maximize subscriber satisfaction.

Capital expenditures to address the over-subscription issue are not continuous and have a longer-term horizon. It takes time to provision more links out of core, node-split cable plants, re-deploy DSLAMs, and increase capacity of the core network. The capacity of the network can only be increased via capital expenditures, and the rate of these expenditures is limited by the constraints of a sustainable business model. Technological advancements also allow increases in capacity expansion in the network to become increasingly more cost effective over time. Therefore, capacity of the network will expand but will it be able to keep up with the demand for network capacity?

Network capacity expansion is a long-run effect on the broadband network. Short-run controls of capacity are not possible; what is needed is an ability to modulate the demands on network resources.

Issue 5: No active control is a sub-optimal policy

A passive approach by the network operator is a policy decision in itself – one that results in multiple entities randomly contending for network resources, all the time, without any prioritization of consumption volume, tier class, or application awareness.

This approach does not attempt to maximize utility of the network and will lead to an overall reduction in satisfaction by all parties. This uncontrolled behaviour will destroy the Internet commons.

Such an approach would provide optimal utility of the network under the ideal condition that all subscribers, applications, and content are behaving in a similar manner. Under such ideal conditions, an unbiased random application of network resources is appropriate. But, real networks do not reflect this ideal.

Figure 3: Ideal vs. observed network patterns.

Under the non-normal distribution observed in real networks, heavy users are unduly benefiting from the network at the expense of light users. The distribution of light-to-heavy users has an 80/20 split, 80% of the resources are consumed by less than 20% of the users/applications/content.

For example, multiple subscribers share the same bandwidth on the QAM (Quadrature Amplitude Modulation) link in a cable network. Sending/receiving email is perceived as higher value than an offline P2P file download; yet left unconstrained, a light user who occasionally wants to send email may have to wait minutes for the email to leave their outbox due to the random contention for this precious and shared bandwidth with the neighbour’s P2P download.

In this sense, the current situation of random unmonitored broadband network contention is like an unmonitored schoolyard; network bullies will control access to the playground, and many of the meeker users will miss their chance to play on the swing set.

Allocating responsibility: Network providers are the backbone

Given the growing imbalances that threaten to undermine the broadband experience for all stakeholders, it is the network provider’s responsibility to build, operate and expand the network to meet the performance requirements and expectations of each stakeholder. Only the operator has the network visibility to affect positive change. And it is only through subscriber choice that given applications and content providers are allowed ‘onto the field.’

It is also the responsibility of the operator to manage the operation of the network such that it is performing at its peak efficiency, and that the maximal utility of the resources at hand is achieved.

Solution: Marginal utility

Faced with all competing demands by applications, subscribers, content providers for network resources and the realization that they can not all be 100% satisfied simultaneously, a framework to maximize the combined utility of the broadband network would appear to be beneficial to all parties.

As a framework to discuss how a network operator may be able to discuss and perform tradeoffs between these diverse users of resources, it is useful to apply the concept of marginal utility. The incremental value of an additional consumption of some component (in our case, network bandwidth) diminishes as each additional unit is added.

This means that the marginal and total utility have the following types of curves:

Figure 4: Marginal and total network utility.

The key concept for this model is that below a certain bandwidth level, the utility is essentially zero. Below 64 kbps, an uncompressed VoIP (voice of IP) session will begin to degrade until it is rendered essentially useless, while bandwidth beyond 64 kbps does not offer additional utility.

Understanding the shape and limits of these curves for the applications, subscribers and content providers has the potential of allowing the network service provide to construct an aggregate utility curve for all the constituents in the network.

Conclusion: Winning a zero-sum game

Since there are insufficient resources in the network to satisfy the full demand of all subscribers, then any control would result in taking resources from some subscribers and allocating them to others. This reallocation of resources is a zero-sum game.

Faced with a slow-moving over-subscription through capacity expansion ability and rapid changes in application deployment and development on the Internet, network operators face ongoing and dramatic differences in network resource use by individual stakeholders.

It is the role of the broadband network operator to provide a mechanism that can manage these individual player’s demands on the network to strive to provide the maximum overall benefit for their entire subscriber base.

Since capital expenditures to increase network capacity is the longer term driver to achieve higher levels of utility from the network, the network operator must have an active system in place to manage the demands on their network. Their subscribers will demand it, not explicitly, but by voicing concerns about performance, connectivity, etc.

Recommendations: Network visibility and control

The network operator must have tools to characterize, measure, and control network resources. Visibility into what its subscribers are doing online enables operators to dynamically control the allocation of network resources for the benefit of all stakeholders. Based on the models discussed in this paper, maximum overall utility of the network can be achieved by reallocating resources from subscribers, applications, and content providers of lower marginal utility to ones with higher marginal utility.

It is only through these active allocation techniques of managing the Internet “Commons” and recognizing that it is the responsibility of the network operator to implement them, that the ideals of the Internet Freedoms can truly become a reality.

About Sandvine

Sandvine’s intelligent broadband network equipment helps broadband service providers characterize what happens on their networks, enabling policies that improve customer satisfaction, reduce operational costs and improve profitability. The company’s application and subscriber-aware solutions empower service providers to take control of P2P traffic, stop the proliferation of destructive worm, DoS and spam trojan traffic and ensure subscriber quality of experience (QoE). With over 100 deployments worldwide, Sandvine is protecting the Internet experience for more than 20 million broadband subscribers worldwide.