The TV tax battle

By Phil Lind with Robert Brehl

FEW THINGS GET ME SEETHING like the Canadian television networks’ attempted fee-for-carriage cash grab, the so-called “TV tax.” After everything cable did to increase their TV licences’ value over the years, in 2006 the broadcasters ignited a six-year battle to get us to pay them for carrying their signals. It went all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada, and they came very close to winning.

Just writing this raises my hackles. Ken Engelhart and Jan Innes would joke that fee-for-carriage was my “Wullerton.” I had no idea what they meant until I watched an episode of Corner Gas, set in the fictional town of Dog River, Saskatchewan. The characters all despised the nearby town of Wullerton for its arrogance. Every time the word “Wullerton” was mentioned, the Dog River people would spit in disgust. “Fee-for-carriage made Phil see red,” Ken says. Or as Jan puts it, “You had to be careful even mentioning the words fee-for-carriage around Phil.” (As it happens, in 2011 UBC awarded its first Phil Lind Multicultural Artist in Residence to Lorne Cardinal, one of the stars of Corner Gas. As RCMP Sergeant Davis Quinton, Cardinal was perhaps the most voracious Wullerton spitter in Dog River.)

The fee-for-carriage approach originated in the U.S., but in 2006 Lenny Asper, then CEO of CanWest Global—a company awash in debt of its own making—brought the idea to Canada. And with a new Conservative government threatening budget cuts, the CBC also liked the idea, as did CTV. Then in 2010, when Shaw bought Global, that network stepped back and let CTV—also awash in debt—carry the torch. The CBC was still harping on fee-for-carriage but in a different category, given that it was a publicly funded broadcaster.

All this debt talk sounds funny from someone who works for a company famous for being soaked in it, but at least we figured out our own solutions. And our solutions did not involve others.

In their frantic efforts to claim “We’re Number 1” bragging rights and win the ratings game, both Global and CTV had indulged in out-of-control bidding contests for the rights to popular U.S. prime-time programs. They also spent large amounts buying up other media properties. Predictably, both found themselves struggling to meet the profitability levels their investors expected. Then, on top of all that, the 2008 recession began and advertising started to dry up.

So what to do? Naturally, CTV started crying poor all the way to the CRTC, hoping that a tax imposed on their satellite and cable TV subscribers would bail them out. (As I said, Global did the same until 2010.) CTV threatened that without it they might have to shut down local TV stations across the country. Taxing customers, CTV claimed, was the only way to ensure they’d have sufficient cash on hand to meet their commitments. Heaven forbid they take on less debt, rein in their spending, or explore new revenue opportunities. It was so much easier to ask someone else to do it for you.

Depending on where they lived, many Canadians would find themselves facing bill increases of up to $10 per month—$120 a year more—and for what?

Consumers, along with cable and satellite companies, were already making significant and ongoing contributions to CTV, Global, and other television broadcasters’ bottom lines. By CRTC order, monthly bills contained a hidden 5 percent consumer tax, money that goes to the Canadian Television Fund and is used to subsidize the cost of making Canadian programs. That amounted to more than $150 million per year.

And, at their own expense, cable and satellite distributors had helped make local broadcasters wealthy by substituting Canadian versions of popular U.S. shows for the original versions transmitted into Canada by U.S. networks like NBC and CBS. Canadian viewers don’t get the originals; they see a CTV or Global version complete with Canadian ads—ads that generate the easiest money anyone in the television business has ever made.

Yet, in the case they brought to the CRTC, CTV and Global blithely insisted that they were saviours of Canadian broadcasting. Never mind that they were reneging on their promise to provide their signals free and to produce Canadian programming in exchange for the privilege of receiving an exclusive broadcast licence.

We won the first and second CRTC hearings, but lost the third. In 2010, CRTC chairman Konrad von Finckenstein astonishingly flip-flopped and granted the over-the-air broadcasters the right to charge a fee for their signals. We took the CRTC decision to the Federal Court of Appeal, and then we ended up at the Supreme Court of Canada.

And that’s when things got really interesting.

First off, the landscape changed dramatically when Bell bought CTV and Shaw bought Global before the case even got to the Supreme Court. Both Bell (which owns a direct-to-home satellite company) and Shaw (with both cable and satellite) had been vocal anti-tax supporters. I wondered what the networks’ position would be now.

“To no one’s great surprise, Bell suddenly became wildly in favour of the tax.”

To no one’s great surprise, Bell suddenly became wildly in favour of the tax. But Shaw, although a little less vocal publicly, stayed with us; they even helped fund our legal challenge. This move by Brad Shaw certainly ensured that Shaw was in the cable camp. It was now Rogers, Shaw, and Cogeco that would be the main cable companies fighting the TV tax. (Vidéotron owned a Quebec network, and so was on the other side too.)

At this point CBC entered the fray as CTV’s ally, somewhat negating their loss of Global as a supporter.

So off we went to the Supreme Court. Now, at Rogers we’d pioneered the art of practising for appearances before the CRTC. Before every hearing we’d work long and hard on our rehearsals, anticipating any questions that might be asked and formulating decisive answers. The same would be the case now. We hired two former Supreme Court justices—Michel Bastarache from Quebec and Jack Major from Alberta—who listened to our legal team’s arguments, critiqued their performances, and asked penetrating legal questions. Our two main lawyers were Jay Kerr-Wilson, an expert on copyright law who worked with Bob Buchan, and Neil Finkelstein, one of Canada’s best-known litigators who recently passed away at age 66. We did have one snag, though: Finkelstein wasn’t interested in coming to the rehearsal. Over his career he’d taken 28 appeals to Canada’s Supreme Court, and didn’t feel that practice was necessary. I had Bob call him and persuade him otherwise. As Bob recalls, “Finkelstein came, and after the rehearsal he told me he enjoyed it and found it very helpful.”

The case hinged on copyright: specifically, could Canadian broadcasters legally stop cable and satellite from freely taking their signals when they didn’t hold the copyright to most of their programming (whether popular U.S. shows or independently produced Canadian shows)? “I’ll never forget the rehearsal that day,” says Jan Innes. “We totally changed how we positioned our case based on the input from the former judges.”

Ken Engelhart recalls that our argument boiled down to this: “We know the CRTC has the power under the Broadcasting Act, but because it’s copyright, they can’t do it. And the other guys were saying ‘Copyright, schmopyright. It’s broadcasting and we’ve got the power of the Act.’”

The Supreme Court ruled that the CRTC had overstepped its authority in granting CTV and other companies the right to charge for their signals because the broadcast regulator does not have the authority to rule on copyright issues. We won the case, but it had been touch and go. “As Phil always says, ‘When regulators overreach, they get slapped down,’ and that’s what happened here,” Ken remarks.

The Supreme Court decision was issued on December 13, 2012. Pam Dinsmore and I were celebrating in the office of Rogers CEO Nadir Mohamed when I introduced a little doubt, cautioning that the devil is often in the details, and that the decision might contain some legal argument that could lead to the court re-examining the case. “We can’t get ahead of ourselves,” I said. “We’ve still got to read the decision.”

To which Nadir responded, “Phil, we don’t have to read it, they do!”

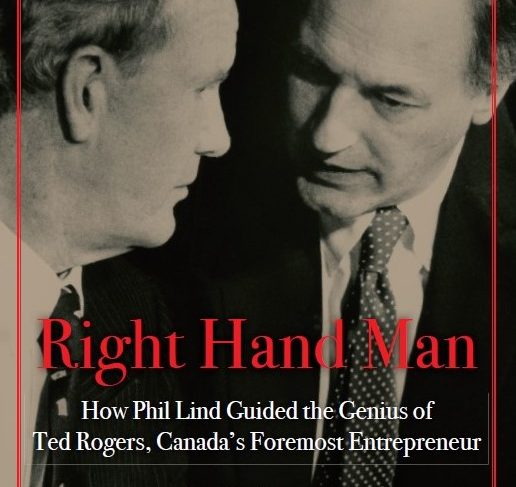

This excerpt is from the new book Right Hand Man, a memoir written by Phil Lind with author Robert Brehl. Lind, still vice-chair of the RCI board of directors, was known as Ted Rogers’ strategic “Abominable No Man” and spent 40 years helping Canada’s foremost entrepreneur build Rogers Communications, one of Canada’s biggest telecom and media companies. In the wide ranging, often hilarious book, Lind tells his own story about some of the biggest deals Rogers ever made and why he was well suited to the task of helping guide his boss, even after surviving a serious stroke. On Thursday, we’ll find out when, and why, Lind decided not to vote Tory for the first time in his life. Published by Barlow Books, Right Hand Man is available on Amazon.