EVEN FOR A PROPONENT of spectrum set-asides, mandated roaming and mandated tower sharing, the rules surrounding the 2008 advanced wireless spectrum auction, which were released Wednesday afternoon in Toronto by Industry Minister Jim Prentice, aren’t quite a slam dunk.

MTS Allstream’s regulatory chief Chris Peirce was pleased Industry Canada had accepted his, and others’, argument that a leg up was required for newcomers to enter the space and increase wireless competition in Canada, but was non-committal about putting the rules into practice. “At a policy level, the government and the ministry have clearly gotten it. They understand that this is an important opportunity for new entry and more competition for Canadians,” Peirce told Cartt.ca. “At a policy level, for all of those reasons, it’s good to see.”

However, “at a company level, we’ll have to see because it’s not about a national license, it’s still a regional or metropolitan approach and obviously they’ve changed the pricing dynamics from what was in the original call,” he added. The original call talked about national players, not regional, such as is set out in the new rules,

And, in an official company statement, Peirce’s CEO, Pierre Blouin had no further answers, except to say MTS might look for partners. “With today’s announcement, there is an opportunity to bring renewed competition to a strategically vital industry. The result should be more choice, better prices and innovative new services for Canadian consumers and businesses,” he said.

"As to our own participation in the auction, important steps remain. We will not make any decisions about whether or how to proceed until we have completed our analysis of the rules and discussed the range of strategies available for entry with potential partners,” added Blouin.

Quebecor, which plans a regional network in its home province to start with, is unconcerned with the regional divisions within the spectrum chunks being made available and has committed to a $500 million build-out.

The primary head-scratching aspect to the new rules is that there is no national block of spectrum to pursue. Instead, there are six different blocks available containing a total of 264 different licenses, covering most of Canada, but based on various service areas in each province and territory.

Michael Hennessy, the vice-president wireless, broadband and content policy at Telus said he was “deeply disappointed” with the ministry’s decision. “We think by trying to license multiple entrants using local blocks, we’re really creating a recipe for the bankruptcy of small companies… If we’re really trying to be more competitive with the U.S., that’s an issue of scale and you don’t solve that issue by making companies smaller.”

Indeed, one of the problems faced by former wireless competitors Clearnet (bought by Telus) and Microcell (bought by Rogers) was that the network coverage concentrated on major centres and large gaps in networks upset customers then and are likely to be even more of a problem nowadays, if allowed to happen, although mandated roaming should take care of that. (Ed note: As a former Fido subscriber, prior to its purchase by Rogers, I dropped the service because there was only intermittent wireless coverage between Toronto and Ottawa, or Toronto and Windsor, for example).

“I worry that by dividing up the spectrum at a time when bandwidth-intensive applications require more capacity, they actually work to the detriment of consumers if the innovative services they desire can’t be provided because people don’t have the capacity to provide it to them,” Bell Canada’s chief corporate officer, Lawson Hunter, told Cartt.ca.

“I think they’ll seriously have to think about opening up the 700 MHz band earlier than they said they were going to.” That band is the one currently used by TV broadcasters for analog over-the-air broadcasting, which will come available in 2011 when all Canadian broadcasters have to go digital.

As for the mandated roaming and tower sharing? “Roaming and tower sharing by arbitration, which is code for regulation, is just going to re-impose the same kind of non-productive and underwhelming form of competition we had in the wireline market,” said Hennessy. “Basically it’s as if the bureaucrats had difficulty thinking of anything more original than what they’ve done 10 years ago and actually managed to do it worse.”

“It’s a very troubling decision,” added Ken Englehart, vice-president, regulatory for Rogers Communications. “They say they want more competition but new entrants really don’t have to build very much for 10 years. They can roam on our network, so to me that’s not really competition, it’s regulation. And it’s going to cost the taxpayers a fortune because of the set-aside.

“There might not be a lot of network build out of this so there won’t be a lot of innovation, there won’t be a lot of jobs. I’m not sure the taxpayers are getting a lot for their money,” added Englehart.

“It’s a golden opportunity for an investor to buy a bunch of spectrum, roam on our network and then sell out to a foreign company when the foreign ownership rules change. I think it’s a great opportunity for a new entrant. I just don’t think it makes a lot of sense for consumers or taxpayers.”

(From an aesthetics point of view, however, we’ve got to say that mandated tower sharing/site sharing is a good idea because having towers everywhere or transmitters sprouting from the tops of every tall building like weeds is just ugly – and has the potential to be a little more dangerous the more of them there are.)

The incumbent players all insisted Wednesday that the ministry – which put together a full-on political performance at the King Edward Hotel in Toronto, complete with a display and podium dressed in new artwork emblazoned with the tagline: “Putting consumers first” – got it all wrong. Unlike what minister Prentice had to say, rates are low in Canada, some of the lowest in the world, and that while penetration does lag many places in the world Canada is ahead of NAFTA partner Mexico and just behind that of the United States.

“No matter what people say, we have extremely low rates in Canada,” said Rogers Communications’ vice-president, regulatory, Ken Englehart.

“As we said, prices are a lot more competitive and pickings are going to be a lot slimmer than the people in Ottawa seem to anticipate that they are,” added Hennessy.

So, with this leg up, look for a long list of bidders when the auction starts on May 27, where the opening bid for 40 MHz of spectrum in Toronto will be $64.2 million, while such a bid in say, Moose Jaw, will start at just $256,500.

And however it all turns out, Canadians will have more wireless choice – and prices will be lower. What the government has done with these new rules, added Peirce, is simply the least it could do to move to a more competitive market.

“Without designating spectrum for new entrants to bid on and without mandating roaming and without tower sharing, there was just no possibility of new entrants – or of even getting investors to support a bid, let alone succeeding in one,” he said.

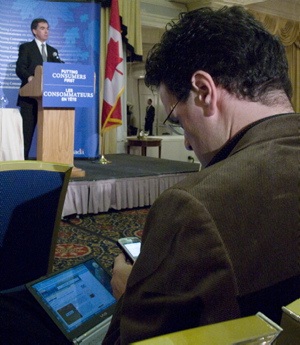

Below is a photo of yours truly that we were alerted to by a reader and that we borrowed from CBC.ca. It’s a true picture of news reportage in 2007. Industry Minister Jim Prentice is speaking in front of me but open is my laptop – while my unseen digital recorder listens for me. Having just posted my story at about 4:10 p.m. using Toronto Hydro Telecom’s not exactly robust wi-fi, I was also using my Blackberry to get Cartt.ca’s special news release on the AWS auction rules sent out right away (and, near as I can tell, speedily beating all the other news organizations in the country to the punch, I might add…)