PIAC, Competition Bureau, CCTS push label as important opportunity

By Ahmad Hathout

The CRTC must take a light-touch regulatory approach when it comes to determining how internet service providers (ISPs) present certain technical plan details, as being too prescriptive risks providing unnecessary information while adding implementation costs, according to several large service providers.

The gist of the ISP argument – both large and regional – can be distilled to some form of the following: they already provide the necessary information they believe an already-informed public should know, and the one example of a mandated “broadband label” – that is the one in the United States – is allegedly not working as planned. The result, they convey, will both be a more confused customer base and service providers, already subject to an internet code of conduct, grappling with additional costs for implementation.

That said, the major providers, who say they are all for transparency, argue that if the CRTC must impose something, it should do more guiding than prescribing – want us to advertise additional metrics? We can do that, just don’t tell us where and how we market them.

The comments come in response to the launch of a CRTC consultation proposing to standardize the presentation of information related to internet plans into a form similar to the “nutrition label” on food packages. The consultation, and subsequent hearing on June 10, comes after the passage last summer of Bill C-288, which mandates that the CRTC launch a proceeding to figure out what a standardized label should look like.

The bill’s author, Conservative MP Dan Mazier, filed a submission expressing concern about the language of the consultation – that “the CRTC is considering whether internet service providers should be required” to have such a label (Cartt’s emphasis). Mazier said this is a non-negotiable – ISPs, by law, must be ordered to display such information and the regulator must figure out how that disclosure will pan out, he said.

The bill requires the disclosure of service quality metrics during peak periods, including typical download and upload speeds, and any information required by the commission that is in the public interest.

Mazier further suggests the commission include service quality measurements like jitter, packet loss and latency in the label; include a standard for fixed-wireless technology; make metric measurements reflect the different regions of the country, specifically at its most granular level, currently measured at what’s called Tier 5; and ensure the “peak” period – widely accepted as between 7 pm and 11 pm – is as narrow as possible.

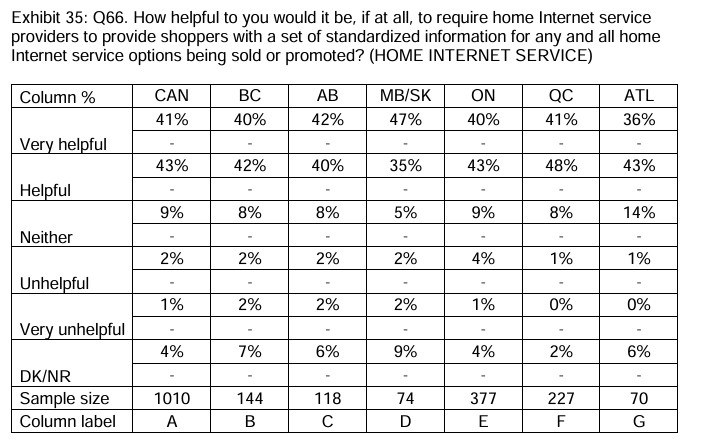

Most submissions reference the CRTC’s commissioned public opinion report, conducted by Earnscliffe Strategy, which found that 84 per cent of those surveyed found a standardized broadband label would be at least helpful.

But depending on who you ask, the report’s findings can be used for or against the label.

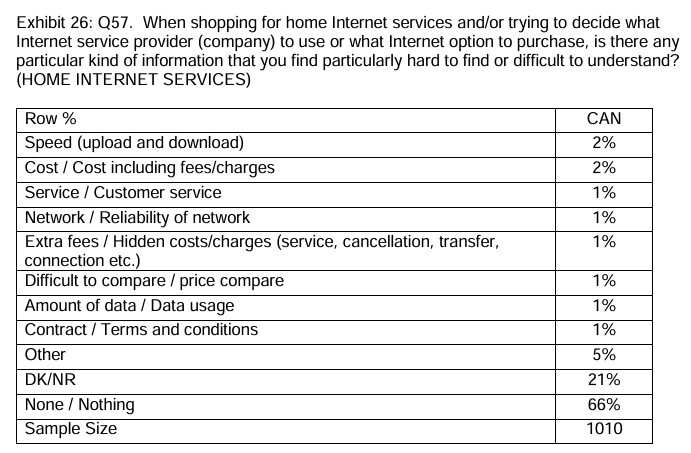

For example, the Canadian Telecommunications Association (CTA), the trade group representing the large providers, references a finding in the report that shows two per cent or fewer respondents found any specific type of product or plan information difficult to find or understand when shopping for a plan. A further one per cent found it difficult to compare services, providers or prices, the trade group notes.

This, the CTA argues, is the result of years of experience on the part of the providers to craft their marketing materials to make the information as accessible as possible. Abandoning that tried-and-true for an “unproven standardized” format is “unwarranted” and “would require service providers to develop complex and costly systems and processes without providing an incremental benefit to consumers,” the CTA argues, adding the focus of the proceeding should be on broadband speed advertising, such as the typical download and upload speeds during peak periods mandated by Bill C-288.

Rogers says, at most, if the CRTC must force disclosure of a metric, it should be those typical peak period internet speeds. “Requiring the disclosure of any service quality metrics beyond typical peak period speeds could well mislead consumers into thinking such metrics are relevant to their experience when they are not,” Rogers says in its submission, adding that information should only be required at pre-sale, as it says the Internet Code provides ample protection for consumers post-sale.

“Any requirements that are not demonstrably necessary will needlessly trigger costs that could influence prices for consumers, while providing no meaningful benefit in helping them understand and make decisions about plans,” Rogers adds. “Moreover, the costs of implementing regulations can impact product innovation, network investment, and expansion. For providers like Rogers, any mandated changes will require updates to multiple IT systems, across large and complex infrastructures, with finite human and financial resources with which to implement them.”

Bell argues forcing a standard with highly technical information will just serve to overwhelm customers and add a cost burden on providers. It adds that only the required information should be made available in an “easy to access and understandable manner.”

“At most, we believe the Commission should only require that certain information be included and provide the flexibility for ISPs to display the information in the appropriate platforms,” Bell says. “If the Commission determines that a broadband label is nonetheless necessary, we believe that providers should have the flexibility to present the information in the appropriate platforms.”

The CRTC-commissioned report, Bell further argues, shows a population satisfied with what to look for when shopping for internet services. “These numbers are reflective of the significant competition between Internet service providers (ISPs) and the strong incentive for ISPs to offer relevant information to potential customers – as a result, Canadians are generally satisfied with the level of information provided by ISPs.”

Telus argues that any standardized label should only include information that is mandated so as not to overwhelm or complicate the shopping experience. Information should target technology type, maximum and median values such as for download and upload speeds, and latency. Its implementation, it further says, should be required of all service providers – no exceptions. It should also afford the service provider maximum flexibility – the CRTC can mandate what information should be disclosed, how that information should be measured, and who should display it, but the ISP should be able to determine how that information is disseminated.

While SaskTel also argues the label isn’t necessary, if one must be adopted, it should apply to all ISPs and only include the most useful metrics: maximum download and upload speeds, average speeds, and latency.

Quebecor argues against imposing such administrative constraints on ISPs so as to avoid the impact on innovation in how providers communicate with their customers. “A requirement to comply with a single, inflexible format could discourage these initiatives and harm the customer experience,” it said in its submission, adding it is important that the commission avoid information overload.

As such, Quebecor is also asking the CRTC to give as much control to the service providers over how they disseminate mandated information and to avoid including “complex” technical indicators like latency and congestion.

“We believe that standardization based on minimum indicators, such as a download speed greater than 100 Mbps , without requiring the display of an exact speed, access type and technology, would be much more intuitive for the consumer and more flexible for the ISP,” Quebecor argues.

It is also recommending the adoption of a visual classification system, such as a color code, to indicate the level of a provider’s performance in an area, so consumers can quickly assess quality of service. Otherwise, it is suggesting that the CRTC can encourage the promotion of consumer-focused tools, including speed tests and online comparison services so that consumers are aware of what they are getting.

Cogeco is telling the CRTC that if it mandates certain information be disclosed, it allow the provider to determine how that information should be disclosed, such as on their respective websites instead of in a standardized broadband label. That information, it recommends, should be limited to download and upload speeds and latency so as to simplify the shopping experience and to ensure the provider isn’t unnecessarily burdened.

Rural service provider Xplore argues that service providers are already marketing the key metrics that consumers look for, specifically download and upload speeds. Adding more and more information reduces clarity, it argues.

“Standardizing the information in a consumer label may have the unintended effect of stifling innovative service offerings by ISP by standardizing the types of discounts, promotions, and bundles available to consumers,” it says, adding should that standardization be required, the CRTC must consider differences in region and technology.

Eastlink argues Bill C-288 and the proceeding on broadband labels seeks to solve a problem that doesn’t exist, citing the aforementioned CRTC-commissioned report. But if a label must be implemented, additional metrics should be limited to what’s required of the bill, which is the typical download and upload speeds consumers can expect to get.

Far north provider, SSi Canada, also cautions the CRTC against any onerous regulations. “We are concerned that by establishing ever-more detailed and granular regulatory requirements that TSPs must apply, the Commission’s approach to retail regulation is actually undermining the benefits of competition for Canadians.

“As we can attest from our own experience, it is the competitive market – not detailed retail regulation – that will develop services, service packages, and notification methods that best respond to the needs of Canadians,” it adds.

Broadband label an opportunity: advocates

The Competition Bureau says providing consumers with “clear, concise information in a widely recognized ‘nutrition label’ format will lower barriers to switching, empowering consumers and improving competition.”

The watchdog said the label should include key information about price, fees, service characteristics and performance, and the label should be available at the point of sale – that is, where and when they are shopping for service.

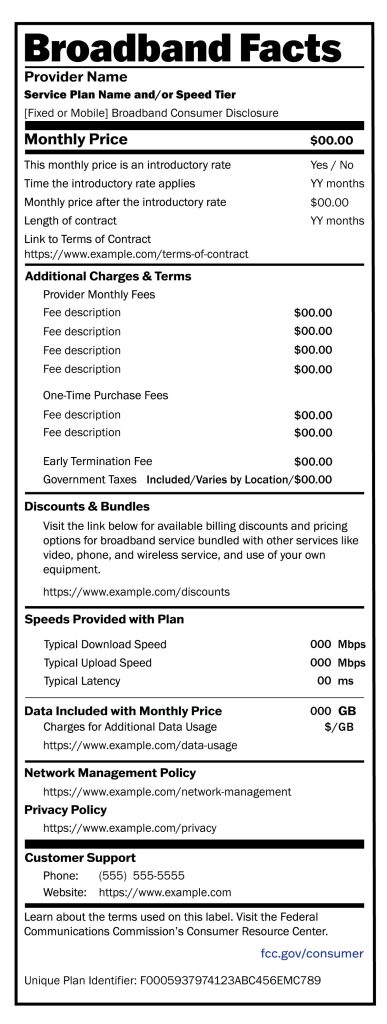

“The Bureau believes that the FCC’s model represents a robust and practical way to empower consumers to make informed decisions about the services that are best for them,” the bureau says. “It could be adopted by the CRTC with little modification, making it not just a good idea but an efficient one, too.

FCC label example

“In the Bureau’s view, the FCC’s approach provides a helpful model that could, with modifications that appropriately reflect the Canadian legal context, guide the CRTC in the development of its own broadband consumer label,” it continued. “As the FCC explains, ‘Consumer access to clear, easy-to-understand, and accurate information is central to a well-functioning marketplace that encourages competition, innovation, low prices, and high-quality services.’”

And while the consultation focuses on internet plans, the bureau says the label should be adopted for mobile wireless services as well.

That is a position shared by the Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC), which laments that wireless services are not under consideration for what it sees as an opportunity to build on the work of the regulators from the U.S., United Kingdom and Australia.

“In analyzing the Commission’s Public Opinion Report on broadband and wireless marketing, it is clear that the broadband label concept is important to consumers, as there is a mixed response to how satisfied Canadians are with their ability to compare information provided by home internet providers, with 22 per cent of respondents saying they are dissatisfied,” PIAC establishes.

It said the labels should include monthly prices, broken down by fee types; information on available discounts; caps on data usage for each month; overage fees; costs associated with cancelling or changing plans; and information on how to make a complaint the Commission for Complaints for Telecom-television services (CCTS).

The label, PIAC continues, should be at pre-sale, through online portals, and on each and any bill the user receives. “This would allow the consumer continuous access to information about their plan and the ability to compare their plan to another at any point in time, as well as the ability to assess whether they are receiving the services they contracted for,” the group says.

The label should also account for urban, rural, remote and regional differences, it adds.

“There are strengths in different countries’ approaches that Canada has the opportunity to draw inspiration from when building our own labelling and marketing rules,” PIAC adds. “However, we caution the Commission not to adopt a ‘copy-paste’ approach in adopting another country’s policy when developing Canada’s marketing and broadband labelling rules. There is no one ‘correct’ answer as there is room to improve on every country’s standardized marketing rules. Canada also has unique geographical challenges that will require enhanced information to be provided to consumers.”

The CCTS – the watchdog that receives consumer complaints – says it welcomes a label that includes the following: internet plan pricing, which should include service offered, time-limited discounts applies, any additional fees, and whether the provider is permitted to change the price; the monthly data amounts and the cost of any overages; and expected service performance metrics, “with context to be able to assess if the service will meet the subscriber’s household needs.”

“The CCTS urges the Commission to include performance metrics in the broadband labels that better reflect the service a customer will receive, rather than maximum speeds they could receive in ideal circumstances,” it says. “Currently, ISPs typically market their service speeds as an ‘up to’ maximum speed. However, ISP contracts and Terms of Service do not guarantee service performance, and ISPs will rely on these contractual disclaimers where there is a significant difference between the advertised speed and the speed the customer actually receives.

“Requiring more specific descriptions of the expected Internet service performance, as has been done in the European Union and Australia, would help bridge the mismatch gap for service quality for Canadian consumers.”

Finally, the Deaf Wireless Canada Consultative Committee (DWCC), which also advocates for members of the deaf, deaf-blind and hard of hearing communities, is also encouraging the CRTC to not just make such labels available, but to make accessible in a variety of formates to ensure all Canadians — regarldess of their abilities — can navigate and fully comprehend the internet offerings.

Screenshot of Conservative MP from Manitoba, Dan Mazier