OTTAWA – Everyone always has ideas for what the CRTC should do – and there were no shortage of them this week at the IIC Canada conference in Ottawa, but today CRTC chair Ian Scott offered a key idea of his own to legislators as they examine the re-writing of the Broadcasting, Telecom and Radiocommunications Acts.

First though, let’s address people telling the Commission what to do. Beginning with a panel session Wednesday morning on day one of the conference – and continuing as a much-discussed theme throughout the two day gathering – was the idea that the CRTC should eliminate its digital media exemption order (DMEO). That order was originally established way back in 1999 under chair Francoise Bertrand, examined and kept under chair Konrad von Finckenstein and once again under Jean-Pierre Blais during his Let’s Talk TV process. It says, essentially, digital media offerings such as Netflix, Amazon, or Crave are exempt from traditional regulation and remains on the books, allowing digital media platforms to thrive without having to worry about any pesky Canadian content rules.

Many IIC panelists and delegates said this week it’s time the DMEO was eliminated and that the digital media players, some now quite massive and global, were brought under the regulatory umbrella so that they must contribute directly to the system in a manner akin to Canadian broadcasters and broadcast distribution undertakings.

It’s an idea worth exploring and the BTLR panel will probably talk about it during deliberations, but as Scott told us in an interview Thursday, “it’s not that simple.”

The Canadian system “is predicated on licensing. It’s a walled garden. You wish to operate in Canada, you’re using public resources, you have certain privileges you obtain a license,” he explained.

“The walled garden has been overrun. They’ve gone around it, over it, through it and they’re on the other side.” – Ian Scott, CRTC

“Now we have a variety of participants in the marketplace coming by a different vehicle. It’s like the walled garden has been overrun. They’ve gone around it, over it, through it and they’re on the other side.”

The last time the Commission took a close look at the DMEO, it chose to keep the exemption in place because, reminded Scott “they said an attempt to regulate them wouldn’t promote or further the objectives of the Broadcasting Act.”

Plus, how on earth can the likes of Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google (which have come to be known as FAANG) and others be regulated by the CRTC anyway? The Broadcasting Act has a broad definition of what a TV show is, but do the videos found on YouTube qualify? What about the YouTube subscription service? Would Facebook’s Stories count, or only when they’re used by traditional media brands?

“I don’t think they’ve really thought through the implications,” said Scott about those calling for the DMEO’s demise because if it were to go, “then by definition, you have to license (FAANGs), and in order to license them, that raises a whole number of things.

“How do you license someone that’s not Canadian, because the current rules say you must be Canadian? What is Facebook? It’s not simple to say. It’s a social media platform but what license are we giving it and for what purpose? Some of them have no facilities or operations in Canada. What I’m saying is it is a considerably more complex question than just ‘get rid of it’.

“Lastly… what are the enforcement tools the Commission is supposed to use to make them (comply with Canadian regs), because we’re lacking those on the broadcasting side.”

While many likely think of Netflix mostly and perhaps Amazon when they say the DMEO should go, simply because their video platforms look the most like regular TV, there are many nuances our regulations were never written to handle.

Amazon, for example, doesn’t actually charge for its video. It comes free as part of Amazon Prime, where members get free delivery of items purchased and other perks for $99 a year. How would a Cancon contribution be calculated from that model? “What’s Snapchat?” asked Scott about another popular platform. “We have content on Snapchat, so are they programming and do they get regulated in the same manner?”

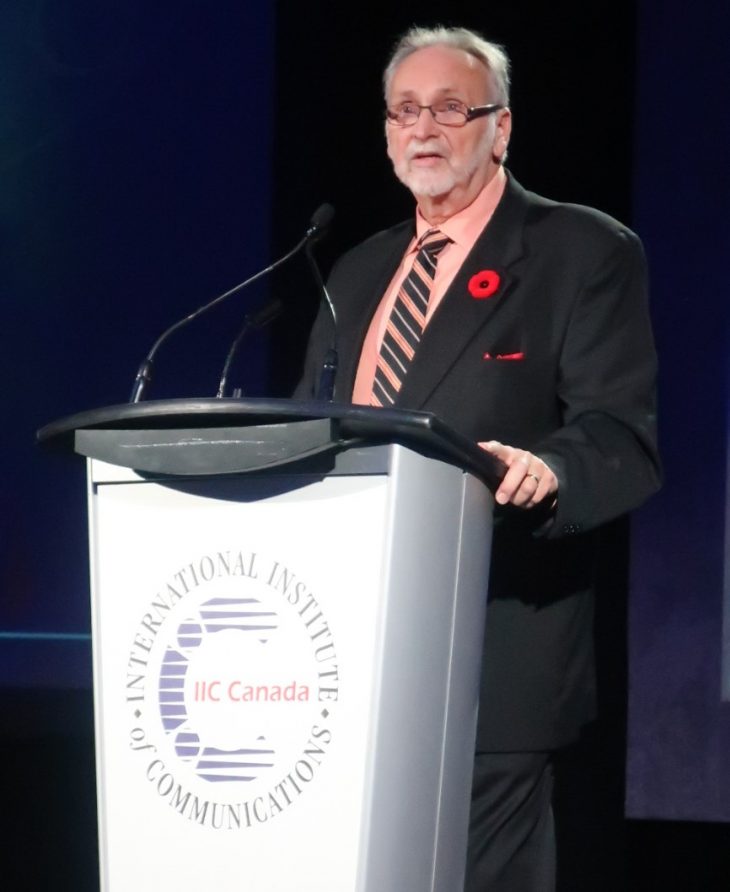

EARLIER, DURING HIS keynote speech to the group, Scott had a little bit of advice for the Broadcast and Telecom Legislative Review (BTLR) panel and the legal eagles who will write new laws based on its recommendations: Give us a clear purpose.

“As they currently stand, the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Acts describe only objectives,” said Scott in his speech. “For example, that the broadcasting system should safeguard, enrich and strengthen the cultural, political, social and economic fabric of Canada. Or that the telecommunications system safeguard, enrich and strengthen the country’s social and economic fabrics.

“It should be the objective of legislative drafters in Parliament to clearly state the purpose of each piece of legislation,” he continued. “Rather than providing the regulator with a long list of attributes that get weighed one against another, the drafters of these new laws should provide us with a simple, clear statement of purpose that will allow the Commission to pursue its objective. Greater clarity on purpose and roles will allow us to be more effective in our work.”

That does not mean Scott wants to see new, prescriptive, rigid clauses. The opposite, in fact.

"If it is world class communications services universally available to Canadians at affordable rates, say that." – Scott

“What’s the purpose of the Act? Presumably, it’s something like to ensure the production, distribution and discoverability of Canadian content and that Canadian content should reflect Canada’s values. That should be the purpose clause, something of that ilk, not a list,” he said to Cartt.ca in an interview post-speech.

When there are lists like there is now in the Acts, everyone sees themselves somewhere and clings to it when they approach the Regulator because the legislation is not clear enough in its purpose. “What’s the point?” he asked “If the point is production, distribution, and promotion of Canadian content, say that. For telecom, if it is world class communications services universally available to Canadians at affordable rates, say that.

“Say what it is you want,” implored Scott, “then give us the flexibility to do what we need to do and we’ll go do it.”