WITH THE CLOSING CEREMONIES of the Paralympic Games September 9th, the Olympic flame was officially doused until Sochi, Russia in 2014.

When that happened, a group of hardworking, unknown, largely underappreciated broadcasters were able to put out the flames in their backs, wrists, eyes and shoulders after working long, demanding hours spread through this summer.

We’re talking about the closed captioners, the people (mostly women) who type all those words you see when your TV is muted, or when you’re at the gym on a treadmill. It’s a vital service for the hundreds of thousands of Canadians who are deaf or hard of hearing (the actual number isn’t really agreed upon). Contrary to what some believe, closed captioning is not a computer-generated stream of words which some piece of Siri-like programming regurgitates what’s said on the air to be displayed on the screen for the hearing impaired. It is manual labour, very often done live. It’s a highly specialized skill.

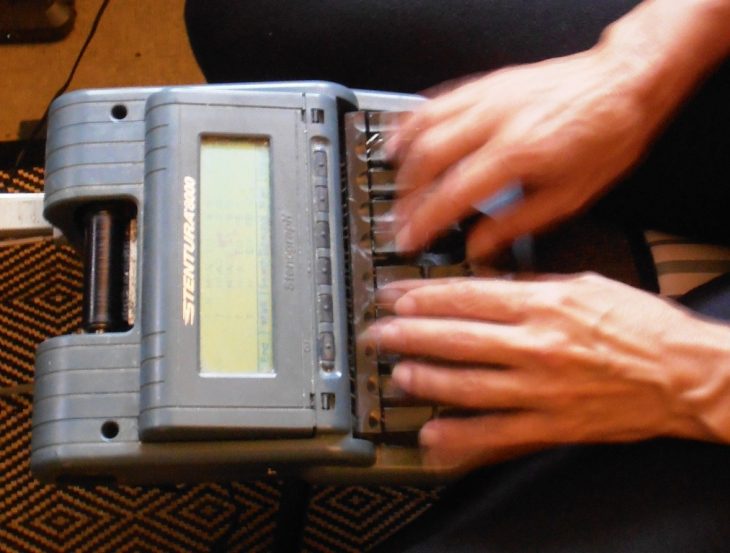

Even saying the words “type” or “typing” is a misnomer. Watching captioner Anna Powell caption live women’s basketball during last month’s Olympics seemed more like someone playing the piano rather than a typist. The captioner for Broadcast Captioning and Consulting Services doesn’t use a QWERTY keyboard but a Stentura 8000, a 24-key stenograph, to output out what she hears. She is quick. Check out the photo below of her hands in action.

Powell started working in her field as a court reporter (as many captionists do) in the main Toronto courthouse on University Ave. in 1981 and years later began doing some real-time captioning during meetings for some hard of hearing groups. One who saw her do that recommended she try captioning television, she interviewed and was hired. Then, pointing to her home office in the second floor of her Newmarket home “for the first three years, I barely left this room.”

Powell memorized the first 40,000-word dictionary she was given in order to master some of what she was listening to and now has her own customized dictionary with over half a million entries. Before Google came along, “it was insane. I did lists upon lists” she said. “I would just search everything. When I started, Google was not what it is now. I had books: Proper name books, I bought the Perly’s map guide and knew all the streets in Toronto. I just would research – towns, cities, countries, you know, all the stuff on the news. I did a lot of Discovery Channel, so I was looking up species. You have your plants. You have your animals…”

However, the Olympics is a different ballgame altogether. It’s ball games of so many sorts – and water games and track, team games, gymnastics and so on – which are rarely seen on television, except in Olympic years. Add to that hundreds of athlete names from dozens of countries all spoken by announcers often talking beyond the speed of comprehension and mispronouncing those names themselves. All that forces Powell, when she’s not captioning, to do tons of research.

“You have to do your prep or you’re screwed,” she said, pointing to a name of a Russian roundballer, Pietlovich which, on the Stentura 8000, takes Powell four strokes of several keys, broken down and keyed by syllables and voila, there it is on the screen, spelled perfectly.

However, TV being TV, Powell is sometimes faced with the surprise of the broadcast being thrown to a sport she wasn’t expecting, (usually because of something unusual or a Canadian doing well). “You might think you’re 100% prepared. We never are, but we try our best, obviously,” she added. “The office sends us lists every day of who’s in the news, the top athletes, all the Canadian athletes. You want to have the most you can… so when we do an event, we’re so prepared for it.”

But when there are surprises and a captioner comes face to face with their worst fear – a name they don’t know how to spell, they just do their best in the second or two they have to think about it, sound it out and try to keep up with the broadcast at the same time. And when mistakes are made, the nature of the steno machine makes it look rather bad, like someone may have mashed a keyboard with their palm. Powell just hopes those reading along understand. “No one uses this machine and (viewers) are all used to a QWERTY keyboard. So, they might be wondering how so many extra letters show up and the name is so butchered, destroyed, as opposed to just a little mistake,” she says. “If this finger just shadows (accidentally presses) the L (key), all of a sudden, I’ve got P-H-A-E-U-P-B for N. See what I mean? So, they’re thinking, ‘How did you butcher it like that?’ Well, writing at the speed of sound, a little shadowing of a letter can destroy the word. We have to be fast but accurate, and it’s not easy.”

One saving grace? Commercials. She can often take the few minutes and find the spellings of something she’s been surprised by on the net, so she can hit her marks on the fly once the ads end.

After a number of years of doing news, sports and many other shows, Powell is one of BCCS’s most relied upon captioners, one whom company president Brian Hallahan can assign to just about anything. Hallahan says on average, his captioners are right 98% of the time – a good thing since the CRTC is serious about this part of the broadcast industry that is invisible to most of us, having just this summer issued new, tough, standards for closed captioning that stress speed, low latency and accuracy.

Pointing to her tangled, printout and technology-laden desks, she continued: “I’ve got the rosters here alphabetically, first names first, last names first, announcers on the side – just things like that. And then, of course, I always print the roster too,” she said of her Olympics prep.

In her office, Powell has two TV screens (one 4:3 and one 16:9) so she can properly position the captioning on-screen in response to the graphics and other action on the air. She still needs the old tube-TV because so many viewers still watch television that way and she doesn’t want to make the captioning disappear into the dimensions of a wide-screen television. Her office is tied into both Rogers Cable and Bell Satellite TV, so she sees what is happening the same time as everyone else – but she has a direct audio link to the broadcaster, meaning she hears what’s happening a handful of seconds before the rest of the audience.

Everything has a backup, from her second steno machine to her laptop with the captioning software. Names and other background information are on her PC screen – and also printed out – and if everything fails (that’s never happened), she still has that hard-wired audio connection to the studio through the regular phone line in which she hears the audio and sends her transmissions.

Powell’s workdays during the Olympics were incredibly busy. “I’ve done a SportsCentre show at 9:00. I do the Olympics from 1:30 until 5:00, then I have a two-hour break and I do them again from 7:00 to 10:00. Some days are a little bit heavier,” she said. “Tuesday I did 11:00 till 4:00 on the Rogers Cup, then I did 7:00 till 11:00, Olympics… I mean, the Olympics is a crazy time. They’re great about spreading it out, so not anyone is overwhelmed with it and you’ve got breaks. But, on your breaks, you’re not living much. You are doing a lot of prep.” Powell preps equally hard for the news she does, too, going online to read what the top news of the day is, prior to six o’clock or 11 o’clock.

This made me think of how I watch television myself, often with a phone or tablet or laptop along side (sometimes even all three), surfing other things to do and read as the TV blares in the background. You can’t do that as a captioner and certainly can’t do that if you’re deaf and want to watch TV. I felt pretty lucky leaving Powell’s office, that I can watch TV the way I do – and that people as dedicated as she are delivering a much needed service to those who’ve never heard the voices of Brian Williams or Dawna Friesen or Peter Mansbridge and have to look at the television screen to “hear” their TV.