Government must look before it leaps with C-10

By Monica Auer

THE DECISION BY THE Minister of Canadian Heritage several weeks ago to drop explicit protection for user-generated content uploaded to social media sites from Bill C-10 led to more attention being focussed on the new Broadcasting Act it would create.

In plain language, the Minister’s change means that while users themselves would not be subject to that Act, it would govern social media services “whose broadcasting consists only of” user-uploaded content. Even if the CRTC is unlikely to demand content posted by millions of Canadians on Facebook or YouTube meet its Canadian content rules, Canadians should still be concerned about the tremendous power C-10 would give to the CRTC.

The CRTC is normally a relatively low-profile federal agency operating with little accountability. It publishes little relevant information about its implementation of the Broadcasting Act, effectively shielding it from Parliamentary oversight and public scrutiny. Established 53 years ago and last reviewed in the 1980s, the CRTC’s proceedings today are largely an insiders’ game with public input accepted but accorded little actual weight. Moreover, while it is often said the CRTC’s role is to serve the public interest, that role is simply not mandated by the Broadcasting Act.

In fact, the current Act imposes requirements that arguably put private interests first: section 5(2)(g) requires the CRTC to be “sensitive to the administrative burden” its regulation and supervision “may” impose “on persons carrying on broadcasting undertakings”.

Before passing C-10, therefore, one would hope members of the House of Commons and the Senate would address some basic questions about the competence, independence, and accountability of the CRTC. Is it fit for the new role it supposed to play? Is it truly independent of government? Are its quasi-judicial processes transparent and fair?

Some members of Parliament have questioned the CRTC’s competence in meeting its mandate. In broadcasting its role is to implement Parliament’s broadcasting policy, which emphasizes cultural sovereignty, jobs for Canadians and the availability of news from a Canadian perspective.

Yet, in its 53 years of operation the CRTC has published next to no information about “cultural sovereignty” in broadcasting. While non-Canadians have invested and held shares in Canadian broadcasting services since 1968, the CRTC has never published annual statistics about changes in foreign ownership, or studies of its impact on Canadian radio, television or distribution (cable and satellite) services.

“Bill C-10 authorizes the CRTC to gather such information and more – but does not require the Commission to publish what it learns. In such circumstances how will Parliament ever know if its broadcasting policy is being met?”

As for Canadian content, the CRTC’s regulations allow most radio and television programming to be foreign: Up to 83% of private TV stations’ weekly programming and up to 65% of commercial radio stations’ popular music selections can be non-Canadian** . Broadcast job opportunities have been shrinking for years and in some cases, broadcasters no longer even hire personnel. CRTC data show tin 2019, 63 discretionary television services whose revenues totalled just over half a billion dollars, employed zero full-time or equivalent staff. For decades, the CRTC has scarcely even inquired about broadcasters’ hiring plans.

In 2016 the CRTC described news as “a key part of the Canadian democratic system and trust that Canadians place in it.” Yet its regulations – whose breaches (unlike those of its policies) attract legal penalties – do not mandate minimum levels of weekly (original) news. (Ed note: Individual broadcasters do have conditions of licence which mandate news minimums.)

While the CRTC has collected information on the amount of original news broadcast by Canadian radio or television stations since the 1970s, its annual reports have never included any statistics about it. In fact, when the Forum analyzed the CRTC’s annual Monitoring Reports from 2008 to 2019, just five of their 3,154 tables, charts and infographics offered information about levels of Canadian content in programming – while 525 reported on broadcasters’ financial performance. Sadly, Canadians have no way of knowing how much Canadian programming is even available, or how online broadcasting is affecting that availability.

Bill C-10 authorizes the CRTC to gather such information and more – but does not require the Commission to publish what it learns. In such circumstances how will Parliament ever know if its broadcasting policy is being met?

The CRTC’s independence from government has been highlighted to the Commons Standing Committee studying C-10. It is true the CRTC is separate from the Departments of Canadian Heritage and Innovation, Science and Economic Development, and Cabinet has rarely published directions to the CRTC and the Commission issues policies and decisions in its own name.

Yet the CRTC’s policies and decisions are not made by all CRTC commissioners, but – due to the Constitutional principle that ‘those who hear must decide’ – by panels of three or more commissioners on behalf of the full Commission. Under the Broadcasting Act the CRTC’s chairperson the power to assign commissioners to each panel. This power is being used. The Forum’s analysis of the 295 CRTC hearings held from June 1998 to March 2018 found some commissioners were nearly always picked for important hearing panels, while others were nearly never chosen.

The chair’s power to decide who decides creates influence over CRTC outcomes – and may in turn give the Cabinet that appoints him or her a certain influence as well. In its current form, Bill C-10 does not strengthen the CRTC’s independence from government by limiting the chairperson’s role in deciding who decides, or by requiring its decisions to be signed by those who make them.

Should it?

Finally, the Commission enjoys nearly unrivalled independence in its day-to-day operations. Take, for instance, public complaints about broadcasting. The old Latin maxim, delegatus non potest delegare, provides that a delegate to whom power is granted may not delegate that power elsewhere without express permission. While neither the 1968 nor the 1991 Broadcasting Acts give the CRTC that permission, it nonetheless approved private broadcasters’ creation of the Canadian Broadcast Standards Council to consider complaints about broadcasters in 1990, and in 2017 decided that complaints about distributors would be addressed by the Commissioner of Complaints for Telecommunications and television Services.

“As for the role of public participation in general, it’s true the CRTC holds hearings and invites public comment. The reality, unfortunately, is the general public’s involvement often seems relatively minor, given little weight in the decisions that are finally issued.”

The CRTC has even stopped publishing statistics about the complaints it receives about broadcasting. C-10 fails to address the issue of delegation, condoning the Commission’s unilateral decision to shift its work to others and creating the possibility of further delegation by the Regulator in the future. If the CRTC chooses not to hear complaints about online broadcasters, who will – and what can “they” really do?

Repeated statements that the CRTC will consult Canadians before enacting regulations for online broadcasters also merit scrutiny. Public CRTC hearings are also not always public. Four of seven CRTC “public hearings” held in 2019 consisted solely of CRTC commissioners and staff; neither applicants nor interveners were invited to participate. The CRTC also issued 39 “letter decisions” in 2019 concerning applications that (along with the decisions) were never made public. And while the CRTC says it will publish all applications submitted which comply with its procedural requirements, repeated access-to-information requests in 2019 found some applications instead vanish into what is effectively a regulatory black hole.

The CRTC denies some applicants due process without publishing its reasons and C-10 appears to assume the Commission operates much like Canadian courts in terms of transparent process – but it does not.

As for the role of public participation in general, it’s true the CRTC holds hearings and invites public comment. The reality, unfortunately, is the general public’s involvement often seems relatively minor, given little weight in the decisions that are finally issued. Consider the CRTC did invite Canadians to make written or brief in-person representations to the CRTC in the 47 public hearings it held from January 2015 to December 2019. Yet data from the Commissioner of Lobbying for the same period show that the CRTC’s commissioners and senior staff had at least 209 private meetings with 59 companies, associations and other organizations, including 68 meetings with Bell, Shaw/Corus and Rogers alone. The CRTC is expected to make decisions based on its experience and the evidence it hears – but who really has the CRTC’s ear?

Insofar as the new fining authority set out in C-10 is concerned, it would be useful to know whether the Commission will adopt in broadcasting the approach it uses when administering monetary penalties in telecom – that is, closed-door meetings in which CRTC staff discuss claimed offences and penalties with those alleged to have breached the CRTC’s rules. While the results of such negotiations may later be published, CRTC enforcement may in the future more closely resemble Let’s Make a Deal rather than the transparent administration of justice that Canadians expect.

Even a cursory review of the CRTC’s performance should trigger alarm bells. Giving it jurisdiction over online broadcasting, the power to order compliance with its regulations and the authority to levy fines for non-compliance without understanding whether the Commission is currently functioning effectively and serving Parliament’s needs would be a grave mistake.

Canada and Canadians do need new communications legislation for the 21st century. Large social media platforms that offer audio-visual programming to people in Canada are part of Canada’s communications system, but simply expanding the CRTC’s authority and powers without ensuring that it is fit for the purpose may not achieve Parliament’s goals. Worse, ongoing court challenges may simply entangle the Broadcasting Act created by C-10 for years.

As it stands, the CRTC’s performance was last reviewed in the 1980s – when computers often fit in rooms, rather in one’s hand. Before giving more power to the CRTC its operations should be reviewed. Clear rules are needed to ensure that Parliament and Canadians can understand what the Commission is doing and hold it to account.

Parliament should update its communications legislation but must ensure that the CRTC operates fairly, transparently and according to contemporary standards of Canadian law. Giving the CRTC even more leeway to do its job is not the answer – making it accountable to Canadians and to Parliament is.

** TV Broadcasting Regulations, 1987, s.. 4:

(7) Subject to subsection (10),

(b) a licensee holding a private licence shall devote not less than 50 per cent of the evening broadcast period to the broadcasting of Canadian programs.

The CRTC defines the evening broadcast period as the six hours from 6pm to midnight: total Cancon therefore equals 7 days x 50% (6 hours), or 21 hours/week, out of a 126-hour broadcast week (21/126) = 16.7%

Monica Auer is executive director of the Forum for Research and Policy in Communication.

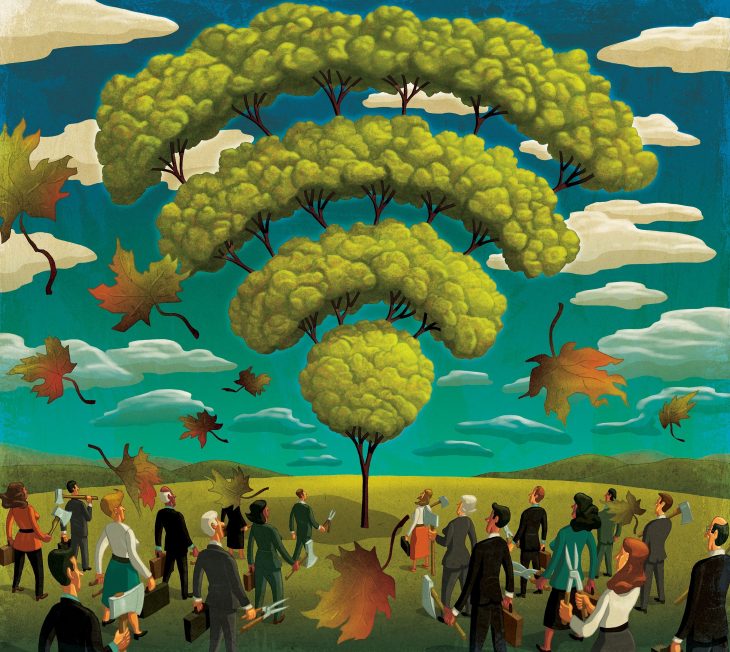

Original illustration by Paul Lachine, Chatham, Ont.