By Howard Law

This is part two of a three-part series – read part one here.

THE CAMPAIGN AGAINST the Liberals’ first attempt at passing the Online Streaming Act as Bill C-10 last spring is poised for relaunch as the House of Commons considers Bill C-11.

In my last post I described what Heritage Minister Pablo Rodriguez is trying to accomplish with C-11. In this post we’ll take a look at the critique by the bill’s opponents.

Like previous criticism of C-10, it’s best articulated by Michael Geist’s prolific posting. His arguments have been picked up by Conservative MPs, Open Media and others.

While for some time Geist and others vocally opposed regulation of even the large American online streamers like Netflix, public opinion seems to have moved on. The Conservative Party reversed itself on that point in both its election platform and recent comments by Heritage Shadow Minister MP John Nater.

Instead, criticism of C-11 focuses on the bill’s inclusion of sharing platforms like YouTube that host commercial streaming of video and music.

The main critique is that the elastic language of section 4.1(2) inadequately distinguishes between commercial programming that will be subject to regulations on one hand, versus exempted non-professional content on the other. Giving the CRTC a free hand to map out regulations at a later date is considered dangerous.

A second argument is that foreign-based streamers and social media platforms “will likely” boycott Canada rather than submit to regulation.

A third argument is that C-11’s “discoverability” provisions empowering the CRTC to require streamers to promote Canadian content is a dangerous and unnecessary interference with platform algorithms and unrestricted uploading.

A fourth argument is that C-11 will do nothing to help and in fact harm entrepreneurial Canadian “digital-first creators” who post on YouTube and similar platforms.

A fifth argument is that C-11 doesn’t change the definition of “Canadian content” certifying what shows can be counted towards broadcasters’ CanCon obligations or are eligible for CanCon film financing.

Let’s evaluate those arguments.

Argument 1: The CRTC can’t be trusted to regulate hosting platforms and will end up regulating just about everything that gets uploaded.

The bill as drafted imposes regulatory obligations on the hosting platform, not the programming or its creator (section 2.1). YouTube will be responsible for streaming an as yet undetermined amount of CanCon and making it discoverable based on its aggregated programming viewed by Canadian audiences. It can continue to host Canadian programming and/or contribute cash to the Canada Media Fund (CMF). None of its uploaders will have any of those obligations. Conservative MP Rachael Thomas repeatedly insists C-11 imposes a levy on uploaders, but this is incorrect.

But C-11 opponents still have a point: the language defining what programming the host platform has to count towards CanCon contributions or discoverability may be too elastic.

If MPs’ trust in the CRTC is as low as Geist’s appears to be, C-11 could be amended to peg the definition of regulated commercial programming to a number of subscribers or an amount of earned revenue.

Importantly, the government acknowledged this political vulnerability in the bill and during second reading in the House on March 29th, announcing that following Royal Assent the minister will issue a directive to the CRTC suggesting where the line should be drawn.

We can expect opposition MPs on the Heritage Committee to demand a draft of that directive.

Argument 2: Foreign streamers might boycott the Canadian market instead of submitting to regulations.

Maybe. Probably not. None of them have threatened to do so. Is it possible that a streamer like BritBox, which has no interest in making Canadian movies, will walk away from 15 million households in the Canadian market rather than pay a contribution tithe to the Canada Media Fund?

It’s worth remembering that Google and Facebook threatened to leave the Australian market over legislation requiring them to contribute to journalism. They backed down when they saw the government was serious. The Canadian market is 50% bigger than Australia.

Argument 3: “Discoverability” requirements interfere with free expression.

Discoverability is streaming-speak for “promotion of content.” On digital platforms, content promotion combines algorithmic feedback of viewing consumption (both individual and trending) with old-fashioned marketing of in-house productions or third party pay-for-placement.

The original C-10 gave the CRTC specific powers to order changes to algorithms to promote Canadian content. C-11 removes that power. Instead, regulated streamers will have a general obligation to promote Canadian content by means of their own choosing. Nevertheless as a practical matter it’s hard to see how discoverability regulations won’t induce platforms to tweak their algorithms to spotlight CanCon more than they do now.

Opponents of C-11 call this “censorship” because, the thinking goes, it contemplates a zero-sum game of winners and losers in competing for audience attention (even though the recommendation algorithms of the host platforms are already doing it).

For that to be even a remote threat, the CRTC would have to impose preposterous standards of CanCon discoverability that crowds out everything else. It might be worth the CHPC MPs asking the minister whether this is the intention of the legislation. I doubt it.

Argument 4: Small digital-first creators get nothing out of C-11 and in fact will be harmed by discoverability requirements on hosting platforms.

This is the focal point of opposition to C-11 from Conservative MPs inspired by a series of blogs and podcasts from Geist. It breaks down into two arguments.

The first is that C-11 will cause Canadian content funding to go entirely to big “legacy” media companies instead of small digital-first producers. Conservative MP Rachael Harder colourfully expressed this in the House:

What is a part of this legislation is actually going after those digital-first creators, those new innovative artists, and asking to take 30% of their revenue to give to traditional, antiquated, outdated artists who cannot make a go of it otherwise.

That’s incorrect. The main beneficiaries of the Canada Media Fund (which presumably would be the prime recipient of C-11-enhanced contributions) are independent Canadian film producers and the thousands of Canadian creative talent and crews they hire.

As well, any digital-first creator is already eligible (and encouraged to apply) for CMF funding. Like any other creator, they have to meet the long-established CAVCO rules that count the number of heads of Canadians in key production and talent posts.

The second argument is that discoverability requirements could backfire on digital creators whose uploads – promoted because they are Canadian content – might get a harmful thumbs down from viewers being “force fed” unwanted content.

There are many questionable assumptions here, not the least of which is that YouTube would undermine its own revenue stream by recommending Canadian content that is unrelated to an individual viewer’s consumption history to which YouTube’s algorithm caters in its recommendations.

The entire controversy may be moot. The government seems to have climbed down on this issue by announcing at second reading in the House that the minister’s directive to the CRTC will exempt “digital first content” from the hosting platforms’ Canadian content:

Mr. Francesco Sorbara (Vaughan-Woodbridge, Lib.)

For instance, a policy direction to the CRTC will make it clear that the content of digital first creators who create content only for social media platforms should be excluded. Of course, individual users of social media will never be treated as broadcasters under the online streaming act, and only some commercial content carried on social media platforms could trigger obligations on that platform. A policy direction will clarify that the content of digital first creators will not be part of the commercial content that can trigger obligations for platforms.

This means that the content of digital first creators will not be included in the calculation of the social media platform’s revenues for the purposes of financial contributions. Content from digital first creators will not face any obligations related to showcasing and discoverability. Canada’s digital first creators have told us that they do not want to be part of this new regime, and we have listened.

This free ranging exemption is a significant retreat by the government and begs the definition of “digital first creator” as we move into a future of “digital first and last” creation where linear broadcasting may become a thing of the past.

Argument 5: Examples of film-makers gaming the system of certifying Canadian content – based on mechanistic formulae of hiring Canadians in key talent positions – undermine the integrity of regulatory measures. So do examples of uncertified films that are as Canadian as maple syrup but perhaps missing a Canadian in a key position. Then there is the loophole of co-productions with foreign film-makers that permit the final product to be certified without being recognizably Canadian.

This is a dead-on criticism shared by some (not all) allies of Canadian cultural nationalism.

To use an unlikely hypothetical, it is possible right now for a Canadian producer to obtain Canadian-content certification for a biopic about Abraham Lincoln so long as enough Canadians are working on the movie.

The rule needs fixing. In addition to using homegrown talent, the cultural authenticity of a film plays a major role in the certification rules of other countries, notably Britain. We could do the same.

Revamping certification rules does not require an amendment to C-11: the mandate for authenticity has always been in the statute. What we need is for the minister to direct the CRTC and CAVCO to revise certification rules to align closer to a British model.

My conclusion about these major criticisms of C-11? Most of them don’t stick and at best they can be mitigated with minor amendments in committee.

What’s really fueling the C-11 debate are diverging views about government regulation in support of cultural nationalism and whether that impacts free expression.

Many C-11 critics see those values as competing, even incompatible.

The existing legislation includes both cultural nationalism and free expression as statutory purposes in section 3 of the act. Since 1968, the CRTC has managed those with a light hand when regulating content, for example election airtime and some advertising content. For the most part, programming standards are downloaded to broadcaster self-regulation through various industry codes.

Nevertheless, many critics of C-11 cherish the Internet as liberator; key to a blossoming of political and artistic expression that circumvents the curation and gatekeeping of mainstream media.

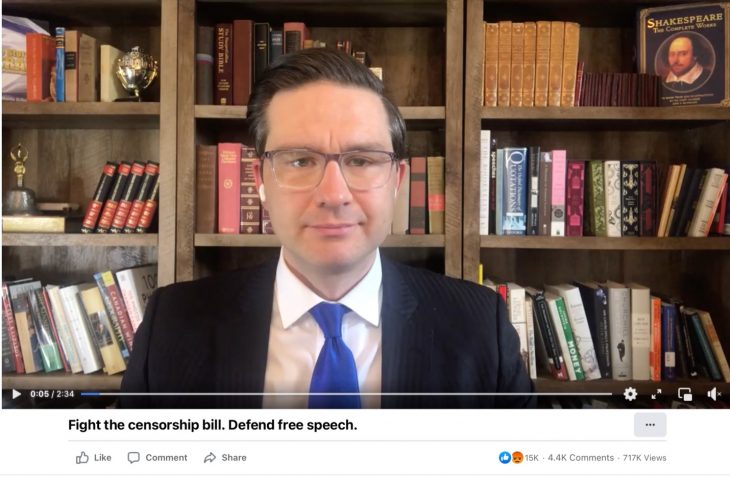

Screen capture taken from a video posted on Facebook by Conservative MP Pierre Poilievre in April, 2021.

Howard Law was the director of Unifor’s local media unions from 2013 to 2021. He now blogs at mediapolicy.ca.