PHOENIX – Legendary Canadian cable pioneer Israel “Sruki” Switzer died at his home in Phoenix late Wednesday afternoon of a heart attack. He was 87.

Switzer, while perhaps not as well known as some other pioneers, had his fingerprints all over the development of cable and telecom networks built across this country and around the world. Respected as a visionary among those whom he helped build these networks, as well as something of a maverick (and a speech he made in 2010 certainly confirms that), Switzer also earned some fame as the guy who demanded Ted Rogers get into the wireless business.

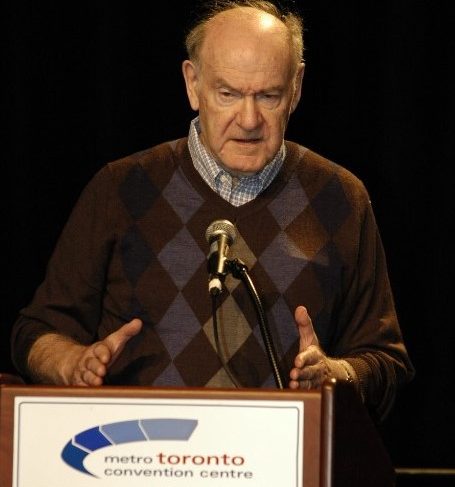

We profiled Switzer (pictured here at an event in 2010), whose late wife Phyllis was one of the co-founders of City-TV and whose son Jay is the former CEO of CHUM Ltd. In his honour, we are re-running that feature below. Funeral arrangements are not known at this time.

The Cartt.ca Interview: Sruki Switzer, Canadian communications legend

“About a month later at a cable show in San Antonio, I bumped into an engineering legend named Israel Switzer, who worked for years at Maclean Hunter Cable. He was now consulting to upstart U.S. long-distance competitor MCI Communications. I knew and respected him a great deal.

“Israel asked me about cellular and what my plans were. I told him I was looking into it. He said he thought it was the future of telecommunications and urged me to get in before it was too late. I had to pay attention to a statement like that from a man of his stature.”

– From Relentless, The True Story of the Man Behind Rogers Communications, by Ted Rogers and Robert Brehl

TED ROGERS VERY OFTEN credited Israel “Sruki” Switzer as the guy who gave him that final push to jump into cellular telephony in 1983, as he recounted in the above passage from his 2008 book.

Phil Lind, Rogers’ vice-chairman, remembers it a bit more colourfully. “Sruki grabbed Ted by the lapels and said ‘damn it all, get into this thing’,” Lind recalled in an interview with Cartt.ca.

So Ted took the advice of Switzer (a trained Canadian geophysicist who ended up designing and building cable, telecom and wireless infrastructure around the globe) and the rest is history. However, while many people know the history of Ted and what became his big red machine, far fewer know the remarkable history of Sruki Switzer.

Those in the TV business might be more aware of his son Jay, former CEO of CHUM Ltd., or of Sruki’s late wife Phyllis, who was one of the co-founders of City-TV.

Back in the 1950s, as cable was a growing infant in Canada and the U.S., Sruki Switzer was busy looking for oil in Saskatchewan when a dinnertime conversation with a friend of his, Ben Torchinsky (then a professor of civil engineering at University of Saskatchewan), turned to television.

“We’re sitting at dinner, and I was talking about television, and we’re thinking there must be some money to be made in this new business besides just broadcasting, which was sort of all tied up and out of reach. And I remembered a magazine article I’d read about something called cable television, so we said, ‘Hey, let’s try that’,” Switzer recalled during an interview with Cartt.ca.

The pair first built in Prince Albert, offering a single channel, CBC, to customers for $4.25 a month ($125 for installation). Situated in a valley, denizens of Prince Albert couldn’t get a signal off-air. “We put a 200-foot tower up on the high bank on the south side and had a one-channel cable TV system,” said Switzer.

Soon, they added a second channel, showing old movies (perhaps the first movie channel ever, anywhere).

Shortly thereafter, Switzer and Torchinsky sold their Prince Albert system and moved down the road to build anew in Estevan, just above the border with North Dakota. “A few miles south of the border there’s a continental divide,” he said. “So that ridge was a barrier for reception of U.S. signals then in southern Saskatchewan. So I figured that if we built a (retransmitter) on this ridge just south of the border that it could provide reception of U.S. signals in Canada.”

What such a tower would also do, too, is provide OTA TV to thousands of folks in the small North Dakotan communities near the border. So with the help of a local service club (the Lions), who obtained the municipal cable franchise, Switzer and Torchinsky “provided the financing to build a (retransmitter) that was licensed to serve the town of Columbus, North Dakota,” explained Switzer.

It just so happened that it was close enough to Estevan that their new cable system, Co-Ax Television Ltd. now had American programming to add to its channel lineup with the CBC. And with a new 970-foot tall tower, the company began serving Weyburn, Sask., in 1962. “As far as I know, that’s the tallest tower ever built exclusively for TV reception,” he added.

Switzer’s story after that is one of a serial engineer, moving from place to place, technology to technology, making friends and acquaintances and business associates along the way, many of whom he would work for or with – and sometimes against.

After Weyburn, he sold computers for a while and then helped built systems in Medicine Hat and Lethbridge, Alta. In 1967 he went to work with Fred Metcalf, who had sold his Ontario systems to Maclean Hunter. There, Switzer rose to become vice-president of engineering, but always retained outside consulting clients, for whom he would work for many years, and in many places, after leaving MH in 1980.

"He would say things that no one else believed and he didn’t give a damn whether anyone saw his vision or not, because eventually, people usually saw that he was right." – Phil Lind, Rogers Communications

However, it was during the 1970s at MH where he helped his late wife Phyllis make a lasting mark in Toronto media.

Then, as now, the CRTC’s policy called for cable systems to carry all local conventional television stations and Sruki came up with an ingenious, if cheeky, plan.

“It occurred to me there could be a local TV broadcast station that would be low power, and UHF. Now in those years – in the early ’70s, UHF was considered not very good business,” said Switzer.

“But if you have must-carry, we could put out one watt of power and cable TV systems would have to pick it up and distribute it on the channel of our choice. It was obvious then, in the early ’70s, as we were building cable in Toronto and I was explaining all this to my late wife Phyllis… so she said, ‘Okay, I’ll do it.’ And I said great because then I couldn’t manage my way, as they say, out of a paper bag.”

Adding another must-carry though might have placed him – as VP engineering at Maclean Hunter – at odds with his employer.

According to Lind, that’s typical Sruki. “He was an incredible visionary, but what an iconoclast,” said Lind. “He would say things that no one else believed and he didn’t give a damn whether anyone saw his vision or not, because eventually, people usually saw that he was right.

“He was constantly a burr under people’s saddles and it always amazed me because he was vice-president of engineering for Maclean Hunter for years and yet he would take policy positions that were totally counter to what the industry thought, to what Maclean Hunter thought,” added Lind.

“He would take on anybody.”

While the CRTC made the new TV station broadcast at more than one watt, Phyllis famously recruited Jerry Grafstein, Moses Znaimer and Ed Cowan to launch Toronto’s City-TV.

Switzer would go on to expand his focus well beyond Canada, as people flocked to him to design and build their communications infrastructure. “I was sort of like a Johnny Cableseed,” he said, creating cable systems in Washington, D.C., Atlanta, Los Angeles, Chicago, London, and worked on numerous projects in the Far East (working for Li Ka-shing in Hong Kong), New Zealand and Columbia.

Switzer was a boundary pusher and early adopter too. He has been recognized by the industry for his pioneering work on the Harmonically Related Carrier concept – a method of spacing television channels on a cable television system, which extended the reach of larger cable systems – and pioneered the use of spectrum analyzers in cable in the ‘50s. He received an NCTA Vanguard Award way back in 1975.

For a guy with this background and influence, some find it unusual that he didn’t come to own a large MSO and make multi-millions selling it. However, adds Lind: “Sruki was never in it for the money. He was one of the few guys, one of the few pioneers who never really had any stake in anything big.”

Guys who are visionaries often profit from their vision, but not Sruki,” added Lind.

“It was more important for him to stand for something, to be a very good engineer.”