BANFF – The recent controversy about cultural appropriation is only the latest Canadian flashpoint regarding Indigenous peoples and their relationship with centuries of non-indigenous immigration.

But can such grappling with identity, nationhood, and creativity be catalysts for constructive change?

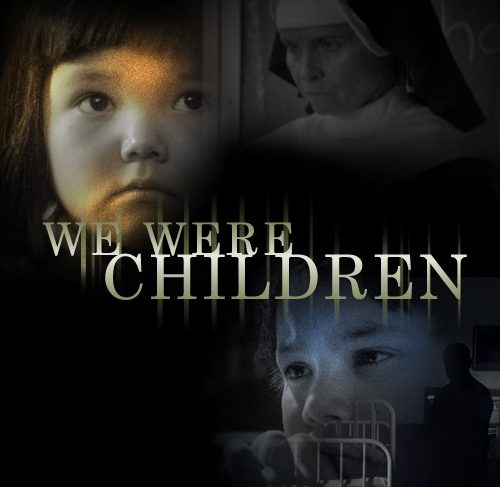

Indigenous stories are already welcoming audiences here and around the world, for example Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001) which won ACCT, Genie and Claude Jutta Awards in 2002; or more recently We Were Children (2012, pictured), the acclaimed documentary about the experiences of First Nations children in the Canadian residential school system.

With the success of APTN, the work underway at the NFB, and Minister Melanie Joly's recent announcement of the first ever Indigenous Screen Office, how can Canadian and Indigenous producers work better together while engaging new audiences and respecting the roots and origins of these stories?

Australia's "Pathways and Protocols" is one model.

This is a Screen Australia filmmaker's comprehensive guide to working with Indigenous people, culture and concepts (screenaustralia.gov.au) dating from 2009, and I would highly recommend the downloadable PDF package.

Our Southern Hemisphere pals regard this text as "essential reading for ALL filmmakers shooting in Australia" – not just producers of Indigenous inspired content. It covers documentary and drama, employs actual case studies, and "encourages recognition and respect for the images, knowledge and stories of Indigenous people.”

Tina Keeper, Cree activist, actress , producer and former Member of Parliament, told the Banff International Media Festival last week she grew up in a northern community "grossly impacted by hydro development… in an era when the Indian Agent still controlled much of life.” I personally remember her hosting of that amazing relief concert for the 1997 Manitoba flood (my home in Prince Edward County is experiencing that same emergency now).

Keeper moderated this Banff round table discussion for over 65 attendees, titled "Forward From Here", in hopes of beginning a fresh dialogue on just these salient issues and concerns. She is perhaps best known for her role as RCMP officer Michelle Kenidi in the CBC television series North of 60, and is currently a partner in the production company Kistikan Pictures.

Keeper was also named the 2017 ACTRA Woman of the Year, honouring her artistic and advocacy achievements: this gal is the real deal.

“When my four-year old son asked about all the awards… I said it was because I was the first native lead in Canadian TV… and he couldn't believe it!" – Tina Keeper

According to her, "our voices were nearly annihilated… but there is a new path being forged… there is reconciliation… but it is also about justice.” Keeper concedes that she "couldn't believe that we even had a second season of North of 60… and when my four-year old son asked about all the awards… I said it was because I was the first native lead in Canadian TV… and he couldn't believe it!"

Michelle Latimer is a Metis/Algonquin filmmaker & producer with Streel Films, actor, and perhaps best known for her role as Trish in the soap opera Paradise Falls with Showcase. Industry cognoscente will also recall Streel Films' award-winning documentary Jackpot which premiered at Hot Docs and received two Golden Sheaf Awards – plus a 2011 nomination for the Donald Britton Award for Best Social Political Documentary.

Her short film, Choke, was named by the Toronto Film Festival as one of Canada's Top Ten films of 2011.

So we're talking major creds here.

Latimer confirmed that partnerships were key to moving forward, but that we "really need our allies too… I was six months at Standing Rock (working on her series Rise) and I witnessed the power of people standing together.”

There was keen applause in the room.

Rise has become a seminal series work, winner of the National Screen Institute Drama Prize, and — with APTN and Viceland Studio Canada as a partnership – possibly the template for going forward. This immersive documentary series takes on colonialism and celebrates Indigenous people worldwide; taking viewers to the front lines of Indigenous struggles.

However, Latimer doesn't want to be pigeon-holed as only making militant TV or movies.

TED Talks, the NAC, and others recently approached her for speaking engagements, but when she resisted the prescribed topics of genocide, drugs and school abuse – preferring herself to talk "about love" and universal values — these organizations apparently balked.

Latimer doesn't want to be "boxed in by stereotypical imagery… I make films about what bothers me in society… yes there's an interest in having diversity… but I don't want to be expected to say certain things like residential schools.”

Kyle Irving is a partner in Eagle Vision, Canada's leading Indigenous-owned production company. Most Canucks will recall his 2005 feature film Capote starring Philip Seymour Hoffman – a hit at Telluride and winner of a whack of Academy, BAFTA, LA Film Critics, and Golden Globe awards – and filmed mostly in Manitoba.

Who knew?

Talk about not being pigeon-holed!

The late Roger Ebert gave Capote a rare 4/4 and wrote it “is a film of uncommon strength and insight, about a man whose great achievement requires the surrender of self-respect.”

But even with that success, and an additional 360 hours of production under his belt, Irving had to be patient and persevering over seven years to get We Were Children produced in 2012. The movie proved to be an astounding documentary account of two First Nations children in the Canadian residential school system.

One of those survivors, Lynda Hart, was sent to Guy Hill Residential School in Manitoba at the tender age of just 4 – and her participation on this film was the first time she had shared her full story… incredible in my view.

Despite the challenges, Irving effused that "I can't believe I'm sitting here now… this kind of conversation was not even imaginable to me over my 16 years of media work.”

Here's an accomplished guy whose done 11 seasons of Ice Road Truckers for The Discovery Channel and is involved in the renewed NBC series Taken Season 2, practically in tears. Kyle shared that "we're at the point now where we need courage… we need to have the power of veto on content and without our voices being altered… we shouldn't have non-Indigenous (partner producers) telling us what to say.”

Moreover, he adds that "broadcasters need to work outside their brands… nobody wanted a story about what happened in residential schools… but We Were Children was a hit on Netflix… it had the highest documentary rating… people want to see and hear these stories. If you want ratings, take some chances with Indigenous writers and producers.”

Indeed, We Were Children (first broadcast on APTN and realized by Eagle Vision, One Television & NFB) went on to win several additional accolades including at the 2014 Canadian Screen Awards.

Other Indigenous creators present offered ideas they were now working on, including content on traditional science, kids fare, trans-media studies, Indigenous language instruction, deep knowledge on weather and land, and as one producer summarized, "whatever will help… we're not looking for just deals, we're looking for respect and responsibility for where our stories come from… work with us and understand the people.”

More than fair comment in my opinion.

Practical problems also surfaced.

There are systemic barriers in such areas as interim financing for Indigenous producers, and that has "forced us into partnerships that aren't ideal and unequal.” Interim financing problems had one Indigenous producer staying at a campsite on Tunnel Mountain so that she could attend this session at the Chateau Fairmont Banff Springs Hotel – no absence of sad and awkward irony there!

And the CMF makes it difficult, according to some present, for all western Canadian producers, "the CMF feels a bit alienating to us out here.”

In addition, with the passing of elders, so much oral history is being lost every day. However, it was evident that Indigenous creators hoped for caring partners "who are prepared to do the work and share the tears.”

Keeper picked up on the later comment and labelled it "historic trauma… we have an ongoing discussion of grief as part of our reality… so there's a lot we don't know about each other… even among our many hundred nations.”.. we are not brown Canadians… we are our own nations with our own diverse identities… we need nation-to-nation work" (see the book The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America, written by Thomas King).

She went on to assert that the only question broadcasters usually pose is "do you have access?" – but then added "but we are not museum pieces… you need to recognize relationship and trust our stories the way they need to be made and talked about… access requires the protocol of Indigenous communities.”

“There should be a pairing of Indigenous show-runners with senior writers… a kind or re-framing of opportunities.” – Michelle Latimer

Latimer suggested that "maybe when we have eight day shoots, one day is about no shooting… but about knowledge and relationship building… that needs to be built into the budget and recognized… and there should be a pairing of Indigenous show-runners with senior writers… a kind or re-framing of opportunities.”

Kyle Irving smiled and added, " I'm looking forward to the day when a feast, a spiritual advisor, tobacco ceremonies, burn medicine, blessings aren't questioned by wide-eyed production assistants but are part of the production process.”

In the non-fiction book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, by Charles C. Mann, he makes the claim that because history is change, there are people without histories, especially in how conventional European traditions treat Indigenous peoples.

The book won the 2006 National Academies Communication Award.

As we roll out the fun, pomp and circumstance of this year's Canada 150 it wouldn't hurt the party if we all took a few moments (at least) to acknowledge in a quiet personal way, not just in a formal speechifying way, that in 1491 there were probably 120 million people living in the Americas – people as different as Swedes are to Turks – but already living in ancient and intricate societies.

We as communicators, as pundits, as leaders of cultural industries, and as media giants have, in my view, a real responsibility to understand and share those facts.

To not do so is worse than Trump on a bad day with his twisted invectives, fake news and alternative facts.

And don't all Canadians deserve much, much better than that?