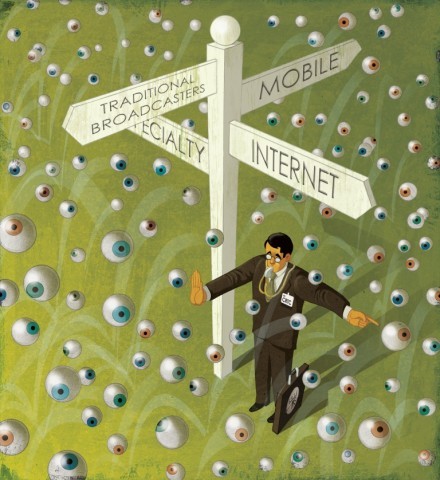

FOR MANY DECADES, THE Canadian TV market had the luxury of being a walled garden protected by the limits of technology. We even carved out a national production industry and nurtured significant cultural achievements next door to the world’s largest content market.

Now, however, digitalized content has climbed over the garden’s walls and caused content markets to globalize and flatten.

We responded to this change with the defensive strategy of vertical integration. We tried to create barriers, concentrating our domestic market, but the problem was this just deepened our dependence on our domestic market and made us less competitive globally. We’ve lost a decade or more heading down the wrong path. It is time for a new approach.

We have to recognize the development of a global market is both a threat and an opportunity and it’s time we move from a defensive position to an offensive one, to build our content production and broadcasting industries for the future. So, what is this future and what are the collective steps we should take to get there?

As we have described in the previous three installments (here, here and here), success in the industry has quickly become about the production of original content. Canada remains one of the world’s biggest producers of film and television content – although this is also under long-term threat. The present opportunity should and could be a boon to our existing production industry, however, instead of seizing the opportunity we have been purposefully shrinking our system into an ever more consolidated market. In order to get out of this deep rut we need to think differently.

Re-thinking scale

THE FIRST THING WE need to accept is our domestic market is too small to develop the industry without the assistance of export revenue. This is a common situation, though, with the U.S. being the primary exception (and even American firms usually make most of their revenue internationally).

In terms of market size, Canada is less than 10% of the U.S. and 5% of the global market. This means that even total dominance in Canada will not bring near enough scale to guarantee the development of an export industry – as we have already seen. This alone demonstrates that calls for more scale inside Canada are misguided. The thinking is backwards.

“So why don’t our broadcasters utilize this as a springboard to export? The answer: vertical integration keeps them locked to the domestic market.”

This analysis is not new to anyone involved in feature film or television financing in Canada, which I did extensively when I practiced law, working on hundreds of television series and feature film financings. Where Canadian broadcasting licenses were involved, they almost always formed a minority portion of the total financing – often less than 10%. Other Canadian benefits like tax credits can often form a larger portion of the total financing than the Canadian license. The entire system is designed to leverage off the Canadian production market into foreign markets, so why don’t our broadcasters utilize this as a springboard to export? The answer: vertical integration keeps them locked to the domestic market.

There is no doubt scale is important in business, but what does that really mean? Typically it’s about having a greater ability to manage the fixed costs associated with running a business. This includes access to capital along with the ability to make long-term investments. However, scale is always measured against competition in a relative way. And this is where we fall short.

Our major corporations’ media divisions are rather small relative to their international competition precisely because they are locked exclusively into the Canadian market. So, what are we to do?

First, we need greater access to global markets. Many of our companies already export, but it must become our primary focus. Canada has an excellent reputation around the world as producer and co-production partner. We have treaty co-productions with most – if not all – of the major industrial markets – and they’re vastly underused. We have many companies with experience abroad and an understanding of the global marketplace. Next, we need a content strategy – or at least a framework – from which to develop a new approach. Markets are global so content owners must build global distribution networks for their products. This doesn’t mean we need to scale single companies globally but instead use the approach that U.S. companies have done for years – partner with local players. Not every company can execute a global strategy like Netflix. And even Netflix is seeking partnerships abroad with local mobile, Internet and television operators to assist with distribution.

“It is perhaps the biggest opportunity on the planet right now and we are missing out because we think domestically when we need to think globally.”

At a time when American companies are preparing global platforms it also means more national players are having to find new partners. We can fill some of those voids. The global marketplace is bursting with opportunities for companies that can bring an aggregated and curated stream of content to platforms looking to increase their customer offerings. It is perhaps the biggest opportunity on the planet right now and we are missing out because we think domestically when we need to think globally.

Our broadcasters must build relationships globally to pave the way for our content production community, which could be through tech platforms like Apple and Amazon, through production partnerships with Netflix, in conjunction with U.S. studios or European partners, or with mobile, cable or telco operators. The rules are currently being written. Our greatest fear should be that we are missing these opportunities because our current, obsolete mode of thinking is holding us back.

I mention broadcasters specifically because many in the production community tend to think producers should be the ones to access these opportunities and that the broadcaster is extraneous. Our experience has taught us that the tech platforms and most are aggregators are looking for content brands that can bring relatively large amount of content – 200 hours or more to begin with a monthly refresh of at least 10% – including original programming. This is beyond the ability of most production companies and producers.

Broadcasters (or distributors) are better positioned to provide this sort of service. Broadcasters have brands, experience with audiences, and an understanding of content marketing. A real partnership between producers and broadcasters is necessary (this has mostly been lacking in Canada), but more as a division of labour than as a division of rights. The digital world offers more transparency, meaning there are more opportunities to share the risk and reward.

Re-thinking competition

In part three, I discussed how content markets are different than those for most products. We consume media frequently, so the real competition is for consumer attention, in a manner that can be monetized. Content markets float all of their content offerings through spillover effects created by marketing tools like best-seller lists, top 40 count-downs, Academy Awards and recommendation engines. “Winning” in this market is not limited to gold, silver and bronze medals. Anyone can get a medal if they figure out how to reach their audience and get paid for it.

Large markets support many players and there is no larger market than a global one. To continue the Olympic analogy, we do not need to compete in every event. We just need to win (or place) in the ones in which we compete. In content markets this is called “Domain Dominance,” meaning you try to dominate only within a specific market segment. It often happens naturally, as producers and artists push towards genres or types of content that interest them or where they see opportunities. However, it helps when you realize that we don’t need to win every race to win – just the ones we choose to enter.

Content markets segment into huge and smaller markets – some that require enormous investments like super hero action movies but others can be smaller markets from pet shows to travelogues to documentaries. Each requires production and distribution partners who understand the creative needs of the specific market segment and how to reach and monetize it. We have been doing this for years – often without thinking about it – when we produce.

Domination comes from hard work and a deep understanding of a market. It’s key to understand competition is not absolute and does require the same sort of corporate scale. The sort of scale required is best described as “intellectual capital”, which really means a combination of skill, know-how and relationships which allow you to put together successful opportunities in the business. It does require more than that – capital is certainly part of it – but let’s start by getting this part clear.

“It will require developing and supporting Canadian entrepreneurs who are prepared to accept the risks and challenges and prove their ability in the marketplace.”

It will require developing and supporting Canadian entrepreneurs who are prepared to accept the risks and challenges and prove their ability in the marketplace. We have many of these skilled individuals in Canada but have failed to recognize their value – instead we keep putting our faith in corporate concentration.

So, what do we need from our government? In my opinion, we need three things. Two are part of the broadcasting system and the first is part of industrial policy. All three are critical.

1. Industrial clusters

An industrial cluster refers to a group of companies and a workforce which develops in a geographic location that brings together a deep pool of intellectual capital in a particular industry. The three greatest industrial clusters in the media and entertainment world are located in Los Angeles, New York and San Francisco. Others exist around the world and collectively Canada has ‘industrial clusters’ of talent in the film and television industries. In many respects, we are already the envy of much of the world outside the U.S.

Any one of our main clusters in Toronto, Vancouver or Montreal is significant on an international scale. We sometimes forget this as we tend to obsessively compare ourselves to the U.S., but if we look even further south to Latin America or across the globe, we quickly see that our proximity also brings huge advantages.

“One interesting statistic out of British Columbia is that 29 out of 30 of the biggest motion pictures in revenue last year had post-production work done in B.C.”

Content production in Canada creates considerable spillover effects, including the development of increasingly deep pools of talent in the production industry. What is most impressive in Canada is not just the depth but also the breadth of the talent pools. Talent is being developed in every area of the business from acting to animation to special effects. One interesting statistic out of British Columbia is that 29 out of 30 of the biggest motion pictures in revenue last year had post-production work done in B.C.

Canada has built these industrial clusters over the past four decades, starting in the 1980s with the lure of lower-cost crews to tempt “runaway production,” as well as federal and provincial tax benefits. The structure of our production industry, including our tax subsidies and our support for Canadian content in our broadcasting system, have combined to create an industry that is impressive on an international scale – even to Americans. This is an asset we are badly underleveraging at the moment.

This leaves two things that Canadian producers need: access to consumers; and funding for productions.

2. Access

Perhaps the most damaging effect of vertical integration on the broadcasting system is the denial of consumer access to independent services. It happened over such a long period of time no one noticed we were like the proverbial frog placed in a pot slowly brought to a boil which fails to notice the temperature increase until it is too late.

Those old enough to remember television in Canada in the 1980s will recall that there were 50 or so channels, all available in every household. These channel brands – including the Canadian brands – were household names. The relationship between channel and carrier was complementary, with each benefitting from a rising market. In the 1990s when the broadcasting system went from 50 to 500+ channels, there were serious capacity issues. It was a combination of both that led to the ubiquity of channel packages.

By the early 2000s it was clear the number of new channels exceeded demand and this led to a major change in the balance of power in the industry. Now, those who facilitated consumer access had even more control and were able to decide which channels succeeded and which would fail. In Canada this led to the “fee for carriage” dispute and eventually the decision to vertically integrate the system.

“That a channel like Book Television, unknown to most Canadians with minimal viewership and little or no original programming, is the most profitable channel in the system (by PBIT) is proof enough of how twisted things have become.”

Now we have the largest media companies owning literally dozens of channels which hold their positions in packages and on the dial due more to their ownership then their viewing numbers or value. That a channel like Book Television, unknown to most Canadians with minimal viewership and little or no original programming, is the most profitable channel in the system (by PBIT) is proof enough of how twisted things have become.

Our system needs to break out of this tired scarcity thinking and restore greater consumer access to all channels. Clearly we need to deal with issues around payments (more revenue sharing) and delivery costs but the technology is now favouring full access systems while delivery, basic storage and bandwidth costs continue to decrease rapidly. All of the channels are already delivered to all of the BDU platforms. Consumers merely pay to have them unscrambled. The new (and highly successful) emerging platforms are all-access with flexible subscription and pricing options set by the platforms. The broadcasting system has to follow suit and figure this out.

The damage this has done to the independent sector in particular cannot be understated. Independents are denied access to larger audiences. This means they cannot make the investments in either original programming or acquisitions required to gain more audience. They can afford the best programs; the problem is that they cannot monetize them. When they have made these acquisitions and proved value there is no path forward because there is no movement in the system. The VI companies control the wholesale market, and everyone else is just trying to maintain revenues.

“This is systemic discrimination based on a policy that has failed and no longer justifies its existence.”

An example from OUTtv: Every year we run a one month free preview on a national basis with all BDUs. It occurs in the same month for all BDUs so we can maximize the marketing effects across the core potential audience. Each year that preview shows a month over month increase of 400% audience share when our penetration on the system goes up to 100% from our base penetration of roughly 15%. Some of these are casual viewers who may sign up, but most do not due to the high switching costs and friction in the system. Our advertising team estimates if we had this carriage year round we would sell at least $1 million more per year and perhaps as high as $3 million more in advertising. This is systemic discrimination based on a policy that has failed and no longer justifies its existence.

With the technology platforms we have no such issues. We are offered full access with the expectation that both parties will benefit. We have seen the same in carriage deals we are negotiating across the world. We launched in New Zealand last week on a platform with more than two million potential viewers. What sense does it make that we have a larger potential audience in New Zealand – a country with 20% of Canada’s population – when we are a Canadian service. This must change, with broader penetration being the norm and any limitations justified, not the backwards approach we have now.

3. Re-creating the virtuous circle of funding

The most difficult challenge for the government and the Commission will be to figure out how to re-create the “virtuous circle” of Canadian production financing – that being the support of Canadian production by the broadcasters and BDUs as a condition of license. In part three, I discussed how this circle worked in the pre-digital era and how it is currently failing. Without funding, the Canadian production system will eventually fail. We must find a way to prevent this.

Over the course of the last decades our governments, businesses and economists have tried to grapple with the impact of the digitalization of our information technologies. Classified advertising aggregators like Craigslist dealt a death-blow to much of the print media by destroying a valuable revenue source. Challengers like eBay, Uber and Airbnb have disrupted previously stable business models. In each case the problem has been that the innovator arrives, destroys economic value and leaves little in the local economy, as revenues are redirected outside the jurisdiction.

The digital economy confounds our normal understanding of both trade and free markets. In the classical view, trade was something we made on the understanding that goods were finite and that creating them involved a trade off between one good and another. Do we grow apples or oranges? Do we make shoes or pottery? Finally, as goods are finite – do we trade them to Japan or to Brazil? The concept of comparative advantage was developed as the Italians made leather and the Swiss made watches, trading the two between them.

“At OUTtv, we knew we had an audience for some of our premium content in New Zealand through reading Reddit boards. Our distributor recognized this as well. This is the future.”

The challenge with digital goods is that there are no such choices. These goods – once produced – can be re-sold an infinite amount of times. In addition, the marginal costs for delivery means there is no such choice on distribution as you can sell them anywhere – globally – with almost no additional cost. The implications for trade are stark. The combination of these factors and the incredible power of network effects on social media platforms means that channels can be built for consumer groups around the world at almost no cost. For example, at OUTtv, we knew we had an audience for some of our premium content in New Zealand through reading Reddit boards. Our distributor recognized this as well. This is the future.

The challenge for governments is how to get these companies to pay into the domestic system. They utilize the existing infrastructure which needs to be paid for and updated. How do they pay their fair share? The answer that seems to be emerging is to charge them on the revenue from the territory. The European Union is looking at this approach and it certainly better suits today’s climate than asking for a consumer tax. A 10% fee payable on net revenues earned in the territory would seem to be a good start. The current withholding tax rate on intellectual property royalties is close to that as an effective rate, so there is already precedent for this.

No doubt many will scream that this fee will be passed onto consumers but this is not necessarily true. The reality is that market access has value and we need to use it to create a revenue stream for our content and cultural products. We already run a very high trade deficit with the U.S. on media and entertainment products. We are their largest export market for such content. Even a reciprocal arrangement would be fine for exports. We may even look at arrangements where the entry of a platform or service into Canada gives them the right to take Canadian content abroad. In many cases they would make back the 10% from sales in other territories.

These funds could be held by a government agency – perhaps a division of Canadian Heritage – and paid annually to Canadian broadcasters. The payments could be tied to Canadian Production Expenditure (“CPE”) requirements and perhaps other criteria regarding the types of content. I would also suggest that these CPE requirements be very high – even as high as 75%. Broadcasters would then have the incentive to make sure the funds are spent on content good enough to provide export revenue. Obviously, they will split their foreign operations into other entities, which would be fine. However, this would tether them to the Canadian system, as access to this funding would provide them with an incentive to produce in Canada. This would stimulate our production sector and leverage off of our current industrial clusters. The broadcasting system would then become a catalyst for exports. This is my suggestion.

On foreign ownership and the economics of digital media

BEFORE WRAPPING UP, a quick word on foreign ownership and the economics of digital media. It has become quite clear over the past decade the economics of digital companies are different than many traditional industries. We have to face up to the fact digital revenues may not replace much of the market value created in the previous era. Future Canadian broadcasters may be much smaller in Canada (although hopefully they can off set some of this with growth abroad). We may also be replacing a few great jobs with more good jobs in our economy. We see this now as the VIs shed jobs monthly while the independent sector is mostly staying the same size or, in our case, hiring/expanding.

“It appears that some of our biggest companies would rather give up than make the hard choices that may be necessary to fully embrace the digital environment.”

The recent calls for relaxation of foreign ownership rules in regards to both BDUs and broadcasters is troubling. Nowhere have we seen an explanation as to how such relaxation will make Canadian companies more competitive. Instead, these calls seem to be more about maintaining share values in the public markets. More than anything, it appears that some of our biggest companies would rather give up than make the hard choices that may be necessary to fully embrace the digital environment. This is discouraging and we cannot let “too big to fail” end in a sell-off of our broadcasting assets either on the channel side or the BDU side.

Even before the creation of the CRTC and CBC, the broadcasting system is a public good. Future generations of Canadians will rue the day when we gave up and sold it off to maintain economic value for a small group of Canadians.

It’s time we use our imagination to re-configure our system so that the core of it survives, while at the same time provides access to the global marketplace. On February 23rd, Cartt.ca ran an interview with Quebecor CEO Pierre Karl Péladeau where he stated (to paraphrase) that we lacked a vision of what we wanted to achieve. I agree. We need to find one.

However, the starting point has to be to accept that we are a small player in a rapidly growing global market and figure out how we can grow with it, not how we can keep it out.

Brad Danks is CEO of OUTtv and an Adjunct Professor of Law at the University of Victoria.

Original artwork by Paul Lachine, Chatham, Ont.