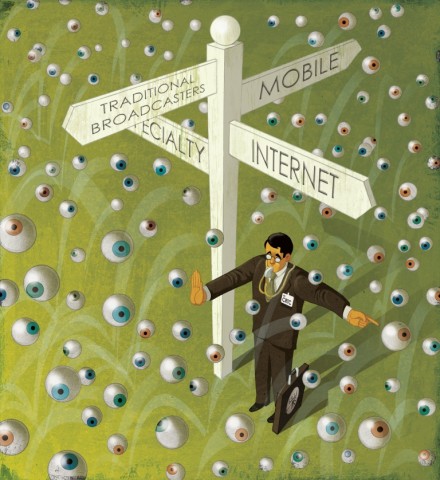

FIRST DISNEY BUYS FOX’S MEDIA LIBRARY, so then maybe Corus buys Bell Media – or the other way around? If so, is this a good idea or a bad one for our system?

A Scotiabank report from December 2017 entitled “Converging Networks” and reported by Cartt.ca has suggested that Corus and Bell Media should merge in order to “make them more competitive.” It’s hard to know if this report is a trial balloon or just mere speculation, but we’ve seen support in other quarters for this point of view.

The research also says Facebook and Google now dominate the Canadian advertising market and that Netflix is now Canada’s most watched outlet by audience share (which is also supported here). The report’s thrust is to make the case that digital revenue must be included when assessing the size of the Canadian marketplace and then offers its solution: more industry consolidation. “The only meaningful horizontal deal left in Canada is BCE Inc. and Corus Entertainment,” it says.

The analysis confirms that if the calculation of their revenues were based on just television assets then it would clearly be too high for the CRTC to approve. If digital revenues and the digital market were included, however, then they would only have 40% of ad revenues, closer to being eligible for merger without major divestments. Those points seem sensible enough – soon everything will be digital so it must be included?

What the Scotiabank report doesn’t do is provide any analysis on the competitive strategy of the merged entity beyond the fact it’s needed for defense. The rationale behind the move and how it would be good for the companies says only, “looking ahead, we expect the combined share to decline because of the faster growth of digital media. By 2020, perhaps the case for a combination from a revenue share perspective may be stronger.” So they would be bigger – but then what?

This rationale may pass muster on Bay Street where raising (or at least maintaining) share prices is the only consideration. However, also at stake is the prevailing strategy in Canadian broadcasting – vertical integration. Before embarking on another round of mergers should we not be asking what the plan is and how it will impact the system as a whole?

Vertical integration as a strategy has failed

CANADIAN BROADCASTING STRATEGY over the past two decades has been about building a system of companies “too big to fail.” Those of us with a long enough memory remember the mergers of CanWest Global into Shaw (2010) and the acquisition of CTVglobemedia by Bell Media (2011) were both pitched with the rationale of making “Canada more competitive” because they would be “bigger companies.”

These mergers did not just make for bigger companies but they bent – some would say broke – the fundamental principles of the Broadcasting Act. The Act is supposed to support diversity within the system. Instead, the system was reconfigured to benefit four major companies – Bell, Shaw, Rogers and Quebecor. This last part is crucial because everything within the system for the past decade has been skewed to benefit these companies. The Commission and all government policies have bent to the belief that this was a strategy that would “save the system.”

“There is no disputing that vertical integration failed to live up to its promise of making Canada more competitive.”

Those of us who attended and spoke at the CRTC hearings in 2008 into the rules governing BDUs and specialty services and in 2010 into the regulatory framework relating to vertical integration will recall that there was always very little in the way of analysis or well thought out strategy. The rationale was stated and restated simply as “Canada needs big companies”. The problem – even more so now than then – was that these merged companies were, and still are, small in comparison to their U.S. competition.

As the Scotiabank report confirms, there is no disputing that vertical integration failed to live up to its promise of making Canada more competitive. In fact, it has done the opposite. The system is actually less competitive, which I will examine later on.

However, there is also no question the goal of concentration has been achieved. Canada now has the most concentrated media and entertainment Industry in the developed world. For instance in Japan, less than 40% of its content is controlled by TV distributors; in the UK it is around 30%; in Germany it is less than 10%.

In Canada there are four major companies, Bell Media, Corus, Rogers Media and Quebecor, that control over 80% of the television market (looking at the English market specifically, S&P reported that in 2015, 93% of the market was controlled by three companies). By way of comparison, these companies each exceed the revenue and value of the rest of the sector: In 2014 the Independent Broadcast Group/GDI members accounted for a combined $1.5 billion in annual revenue, $300 million less than Rogers’ media arm alone. If current trends continue, any one of the four largest BDUs in Canada will see more in profits than the independent broadcasters will see in total revenue for the foreseeable future.

Why it failed

VERTICAL INTEGRATION FAILED because it did not properly take into account the competitive nature of the industry.

The vertically integrated companies have two major advantages within the Canadian marketplace. First, they have considerable scale in captive customers on their distribution platforms. Even with the attrition over the last decade these customers are relatively stable – as they are held by historical hardware lock-in combined with familiar bundled products and other inconveniences which make it less attractive to switch (losing email addresses, losing shows on PVRs, cost of new equipment with some BDUs, advance deposits etc. etc.).

Second, they also wield considerable power in the wholesale market, which ensures they can maintain and even increase the distribution of their channels and thwart all non-vertically integrated entrants, including new broadcasters. When they collectively exercise this power they function like a classic cartel trading the benefits among themselves.

Within the Canadian market the benefits to these companies are obvious. Bell Media, Shaw/Corus, Rogers Media and Quebecor dominate broadcasting market with more than 100 channels representing 81% of revenue and 83% of viewing (CRTC Communications Monitoring Report 2017). It should be noted while Shaw has sold its media assets to Corus – making Corus now a pure play content company – it’s considered vertically integrated by virtue of its ownership by the Shaw family.

In the zero-sum-game of the Canadian market, they are dominant: all other competition within Canada has been quashed.

It has also had a predictable effect on the advertising market. Bell Media has its own rating point and dominates the market. Rogers and Corus share the majority of the rest. Quebecor dominates Quebec. Other players are denied market access and scale, making it hard for anyone else, apart from the CBC, to develop a meaningful advertising business. How this helps the Canadian system as a whole is unclear, but it certainly helps the vertically integrated companies maintain higher revenues, domestically.

How has vertical integration helped these companies become more competitive in dealing with foreign competition, though? This likewise is unclear. In fact, it is not clear they compete at all. Canadian broadcasters by and large act as intermediaries and therefore do not compete directly with U.S. studios and distributors, but acquire content from them.

It’s true the VI companies have been able to acquire most of the best premium content, but has that made the Canadian market more competitive? There is no evidence at all that scale here in Canada posed any threat to Netflix as it entered Canada and built a robust subscriber base now approaching 50% of the Anglophone population.

“The scale provided to the vertically integrated companies only gives them an advantage against Canadian competition.”

There is also no evidence that being vertically integrated has made any difference in the absorption of U.S. content. Apart from Netflix, most of the U.S. content comes to VIs and what does not is absorbed by the independents. As with the advertising market, there is a completely different scale in respect to content acquisition price – there is Bell and Corus, followed by Rogers, followed by everyone else who pay much, much less.

It should be clear the only thing this has thwarted is the development of new competitors within Canada. Super Channel, Hollywood Suite, Blue Ant, Channel Zero, Zoomer Media and OUTtv would all, by now, have grown larger and filled gaps were any available. All of these companies have access to capital but do not have access to the benefits of total market access and the penetration afforded to those who control the wholesale market. New entrants might also have emerged but were discouraged from even entering the market due to the concentration and control of the Vis.

This is the crux of the problem. The scale provided to the vertically integrated companies only gives them an advantage against Canadian competition. They do not compete with the U.S. companies directly except, perhaps, with Netflix. Furthermore, these competitive advantages tie them to a strategy of intermediation, which may be increasingly problematic for the future, as we will discuss in more detail later.

To be successful as an intermediary requires that you can receive more from the Canadian market in revenue then you pay for the licenses. Scotiabank has already pointed out the challenges posed by Google and Facebook in the advertising market. Each new entry either pushes consumers off the broadcasting system or puts more pressure on the VIs’ revenue model as they try to keep premium content in the system – like Bell’s recent deal with Starz. However, the proposed launch of new over the top services by companies like CBS and Disney could make this model challenging for everyone. It is very hard to see how this approach survives in the long term. Therefore, in the end, ironically, the problem with intermediation as a core strategy is that it will not scale, or at least not enough to thwart foreign competition.

It should also be of note that it is the pressure on the business model of intermediation that has caused all broadcasters to ask for relief from the conditions of license as these conditions were imposed at a time prior to the entry of the over-the-top services. The real problem created by vertical integration is even more damning than deliberately picking the winners. The real problem for Canada is that the vertically integrated companies may be both unwilling and unable to play the role that the policy makers assumed they would.

We will discuss this further in the next article.

Brad Danks is CEO of independent broadcaster OUTtv and an Adjunct Professor of Law at the University of Victoria.

Watch for parts two and three of this article coming over the next two weeks.

Illustration by Paul Lachine, Chatham, Ont.