By Tessa Sproule

SEPTEMBER 11, 2001. OUR WORLD WAS REELING. We were drawn to our TVs, showing horrible scenes from Ground Zero in New York. Expert ‘talking heads’ gasped, nodded and filled the 24 hour news channels; car radios provided updates from political leaders as the ‘War On Terror’ began to take shape (“I can hear you!” U.S. President George W. Bush shouted into a megaphone, to a crowd gathered on the pile. “The rest of the world hears you! And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon!”); newspapers printed extra editions, spilling barrels of ink to detail the latest investigations into the terror that had rained down on American soil.

For the news media, it was a pivotal moment, marking a shift in which the internet became the most powerful utility in our information ecosystem.

You’re right, eagle-eyes. I didn’t mention the web once up top. Not because it wasn’t already a dominant force in 2001, but because, for the most part, legacy media failed to take its “pivot to digital” seriously from the very beginning.

It is one of the greatest regrets of my journalism career (so far) that I failed to recognize BigTech’s Trojan Horse as it ambled through the gates of our information ecosystem in the days after September 11, 2001. But I strongly believe we can fix things now, if we work together.

Yes, the internet was here already in 2001 — but it was different.

Most of us didn’t have cellphones (it would take another year before RIM launched its first smartphone, the BlackBerry 5810, and Steve Jobs was still six years away from launching the first iPhone). Those of us who were trying to use the web to follow the news of 9/11 were probably using our desktop computers at work. The majority of us had our browser (probably Microsoft’s Internet Explorer) pointing to our favourite news organization as our ‘home page’ of the web. We would start there.

It’s kind of quaint, when you look back with our 2020 vision today. On September 11, 2001, there was no Facebook for people to check in on their loved-ones. None of it was captured on Facebook Live, because that didn’t exist (Mark Zuckerberg was just 17, not yet building the world’s largest data training set based on the actions of billions of people around the globe in real time).

There was no Twitter to scroll. User-uploaded video was not a thing — YouTube was still three years away. If you were a web-head, maybe you had a ‘weblog’, but most of us wouldn’t visit one of those until 2005. Google was all about search, on the cusp of becoming the world’s predominant search engine (that would happen in 2002, 2004 if you’re a purist); but you had to know what keywords to search in order to find what you were looking for (over to you, Foucault).

Early search engines like Google’s literally indexed the web, which in 2001 was just over a billion pages of mostly HTML-coded text. Put into context, a media organization today probably has more than a billion “pages” of “content” within its own digital ecosystem.

Those early engines also made the choice to rank results by how many ‘other sites’ linked to them, placing the most ‘popular’ at the top. (<snark>Surely an infallible system! No one would create fake sites/people to inflate and skew this approach!</snark>)

‘Popularity’ (or, data we agree is a signal of popularity?) won the day then, as it does now. The headlines we clicked on, the stuff we now “like” or retweet, our literal behavior and life on the web—where we go, what we linger over, how much we despise that actor’s haircut— these are all popularity data signals that BigTech has collected and built its business on.

Technology and storytellers are alike in that — we know there is tremendous power packed in our big emotions: anger, fear, jealousy and love.

That day, September 11th, 2001, woke Silicon Valley up to what we in the media business have always known: humans, with all our messy, beautiful, tragic, terrible and brilliant selves — when we get together, you can feel it.

If you’re a journalist at heart, I bet you want to use that energy in those big moments to help your fellow citizen better understand the world around them. I bet on those big news days, like September 11, your primary concern is how you tell the story as honestly and fairly as possible. The number of people you reach is secondary — but it is hard to resist the “views” count.

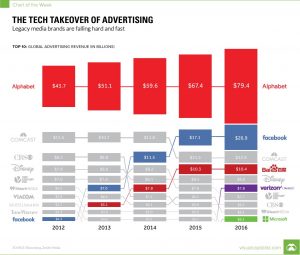

Because, advertising

The tech takeover of advertising began when companies like Google, Facebook and Twitter realized there was significant revenue to be made in the digital distribution of news information content. Today, 97% of Facebook’s revenue comes from ads.

Back in 2001, as now, we humans did most of the work when using the technology platforms. We were, all of us, the real workers of the information economy, serving BigTech’s machines the minutiae of our moments— what we’re up to, where we’re going, what we’re interested in, what we’d like to spend our time (and money) doing — all enormously valuable popularity data signals when it comes to advertising.

Our problematic relationship with BigTech’s approach to predicting what information we need to make sense of the complicated world around us… it started long before anyone had even imagined Instagram, TikTok, Facebook or the Russian Internet Research Agency.

The early days of digital news in conventional media

On 9/11, I was in my mid-twenties, working as a digital producer for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation for an investigative show on CBC TV called Disclosure.

As Canada’s national public broadcaster, on September 11th — and for weeks after — CBC had a massive problem. Canadians could not access our homepage, CBC.ca, because too many were trying to open it at once. Remember, this is before social media and Google News. People came to the news brand they trusted and made it their homepage; our servers at CBC.ca were simply overwhelmed.

Despite being the oldest, most trusted and farthest-reaching network in Canada, and despite how the internet was already the dominant news delivery platform for my generation, we couldn’t make the internet work for us or our audience — Canadian citizens who needed quality, trustworthy information. We were journalists failing to get the story out.

The trouble is, BigTech got there first. And we helped them; by not pulling up our sleeves and doing the difficult business of figuring out how to effectively use technology to distribute our content, ourselves.

If you’ve ever seen a movie about journalism, you know that’s not how the story ever ends.

Looking back, I believe September 11th was a watershed moment, when the media ecosystem moved from an analog, broadcast model towards a digital —and ultimately, AI-reliant pillar of the information ecosystem.

The trouble is, BigTech got there first. And we helped them; by not pulling up our sleeves and doing the difficult business of figuring out how to effectively use technology to distribute our content, ourselves.

Today, we’re facing an even more powerful entrant in the newsroom, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and we must get it right or risk the information economy being defined by again BigTech — not to mention authoritarian tech. And when I say that, I’m not just talking about what’s going on in China; there are many examples closer to home in places like the criminal justice system, migration policy and “smart city” building.

We need to get much better at defining where and when we enlist the help of AI in the crucial decision-making of our lives.

(Part one of four. Next time, we’ll look into how BigTech won the first round, but there’s hope we can all win the next.)

Tessa Sproule is the co-founder and co-CEO of Vubble, a media technology company based in Toronto and Waterloo, Canada. Vubble helps media and educational groups (like CTV News, Channel 4 News, Let’s Talk Science) by cloud-annotating news video, building tools for digital distribution and generating deeply personalized recommendations via Vubble’s machine-learning platform.