But captures much of it anyway, and that’s a big problem

By Len St-Aubin

BILL C-10’s GOAL IS TO engage online streamers with Canadian creators in the production of Canadian stories for Canadian and global audiences. To do that, Bill C-10 proposes to modernize the Broadcasting Act by sweeping-in online (internet) audio and video.

The rationale is the impact of growing competition from unregulated internet audio and video on the regulated ‘broadcasting system’, as outlined in the report of the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Policy Review (BTLR) Panel.

The first article in this series showed how Bill C-10 is problematic for Canadian broadcasting, while this one looks at how the bill would impact the internet in Canada, and whether it’s an effective way to engage online streamers in Cancon. (This is the second of a three-part series.)

Spoiler alert: It’s not

Bill C-10 captures far more of the internet than its intended targets. That ‘overreach’ risks significant collateral economic harm and costs. Moreover, the bill is ill-suited even for its intended regulatory targets.

It’s hard to overstate Bill C-10’s overreach

Bill C-10 would fundamentally change the legal status, in Canada, of millions of apps and websites that stream audio and video over the internet from anywhere in the world — making them “broadcasters” when Canadians access them. Only content that users themselves upload to social media (user generated content or UGC), and UGC-only websites, are excluded. So, the bill’s reach, or overreach, is truly vast.

The internet is awash with audio and video which — in the words of the Broadcasting Act — “inform, enlighten or entertain”: business advertising, tutorials and client service; virtual tours of museums and real estate; opera, theatre and dance; lectures; fitness classes; government information; online newspapers. Bill C-10 captures it all.

Of course it captures the intended targets, like Netflix, Amazon Prime, Disney+, YouTube, Spotify, and many more.

The problem of overreach, when it comes to the Broadcasting Act and online media, was recognized over 20 years ago, in the CRTC’s first new media proceeding. This exchange (begins at p. 2546, line 11008) between then-commissioner David McKendry and lawyer Peter Grant (recently a BTLR Panel member) is worth reading. Mr. Grant’s solution, adopted by the CRTC, was to exempt the overreach from regulation.

High quality audio and video have since expanded exponentially over the broadband internet and Bill C-10 would remove any legal doubt about the Act’s overreach.

By any measure, Bill C-10’s intended targets are a tiny subset of what it captures. Most of that would never be regulated, but Bill C-10 does nothing to circumscribe its targets. The regulator would have full discretion.

That overreach risks significant collateral uncertainty, costs and economic harm. As discussed further below, CRTC exemption is no solution.

Overreach has market consequences

All internet audio and video compete with broadcasters for audiences and attention. Some compete for content and advertising, too. Since Bill C-10’s rationale is the impact of unregulated competition, there’s plenty of room for regulatory creep.

To be clear, it’s highly unlikely the CRTC would, for example, regulate online video for real estate or customer service. That said, Bill C-10’s grey zone is nonetheless vast.

For example, video-enabled online news media compete directly with Canadian TV, as do sports streamers like DAZN. That’s unregulated competition. Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault says online newspapers won’t be regulated. On what basis? Amazon Prime’s entertainment content would surely be regulated, what about its sports?

From a market perspective, there is a clear difference:

- Making foreign streamers finance Canadian drama and comedy supports content that some broadcasters consider a burden and may benefit independent producers.

- If foreign streamers cover Canadian news, or acquire rights to Canadian sports, that’s competition for broadcasters’ core Canadian content.

If Bill C-10 becomes law, the CRTC would decide. It would require the former. It could restrict the latter. Is that what we want in a free and democratic society?

“If the government plans to clarify overreach by policy direction, it should come clean.”

Lifestyle content is a growth area for broadcasters. There’s plenty online too. The closer a website gets to legacy broadcasters’ content, the more uncertainty. That covers a lot of websites — foreign and Canadian.

Like Bill C-10, CRTC decisions would be based largely on input from those who are regulated, or benefit, from regulation.

If the government plans to clarify overreach by policy direction, it should come clean. It’s a valid legal question whether a policy direction could narrow the scope of the Act. Moreover, Bill C-10 would greatly reduce Parliament’s scrutiny of policy directions.

Bill C-10 is ill-suited even for its intended purpose

Internet audio and video benefit Canadians in ways radio and TV never could. They drive innovation and economic growth. Bill C-10 doesn’t get that.

There is a fundamental difference between:

- passively selecting and ‘receiving’ one-way radio and TV; and

- actively accessing, on-demand, audio- and video-enabled websites, on the open, user-driven, global, broadband internet.

That difference means significant economic, social, and cultural benefits for Canadians as citizens, entrepreneurs, creators, and consumers.

Widespread deployment of broadband internet infrastructure has expanded choice and diversity of content. It has lowered costs and created opportunities to reach global markets and earn revenues. Video-enabled websites help e-commerce flourish.

Canadians, strong and free, have responded with a vengeance: We are among the world’s heaviest internet users.

When it comes to entertainment and culture:

- Young Canadian creators are global online stars and influencers on YouTube, with hundreds of thousands, even millions, of followers. Lilly Singh (15 million subscribers), and Quebec’s, Mahdi Ba (1.6 m.) are oft-cited, but just search ‘Canadian YouTube stars’.

- The Stratford Festival, National Ballet of Canada and Théâtre du Nouveau Monde offer online video.

- Innovative Canadian multi-platform media companies like WildBrain and Blue Ant Media provide creative content to the world with millions of subscribers and hundreds of millions of views.

- In the last 10 years, audiovisual production in Canada has grown 85%, including 41% growth in Cancon. Canadian companies producing for global online services include: Bron Animation, Thunderbird Entertainment and Atomic Cartoons (BC); Nomadic Pictures (AB); Mercury Filmworks, Halfire Entertainment and Don Carmody Productions (ON); Couronne Nord and Oasis Animation (QC).

Bill C-10 nowhere acknowledges how market-driven internet audio and video benefit all Canadians and — yes — contribute to cultural policy objectives.

It’s a blind spot. Indeed, despite its rationale, Bill C-10 mentions the internet only twice — in a definition, and the UGC exclusion. Competition is never mentioned.

The Broadcasting Act was never meant for online media

Despite technology-neutral definitions, the Act is grounded in legacy broadcasting. It’s command-and-control regulation was conceived for a limited number of radio and TV services, broadcasting one-way, in Canada, with controlled and controllable market entry, and finite distribution channels: radio frequencies, cable-TV, or satellites.

“Bill C-10 would harness internet race cars to broadcasting horse-drawn buggies.”

Audio and video streamers operate in a vastly different market: uploading content for worldwide, on-demand, access, with unlimited competition, on the open broadband internet.

Bill C-10 would harness internet race cars to broadcasting horse-drawn buggies.

Consider YouTube and its many Canadian creator and entrepreneur channels. They aren’t “state certified” — but they are Canadian content. How would CRTC rules apply? Making YouTube spend 30% of gross revenues in Canada on Cancon could only reinforce its market power vis-à-vis any would-be Canadian competitor.

To Bill C-10, internet audio and video look just like legacy radio and TV

Bill C-10 empowers the CRTC to apply essentially the same heavy-handed suite of conditions of service to both legacy broadcasters and whatever “online undertakings” it decides to regulate. Cancon obligations are just the start.

It expands the CRTC’s authority to make regulations; creates new, highly intrusive, powers to extract — and disclose — confidential business information; and new monetary penalties to enforce compliance.

There is one significant difference. Only legacy broadcasters would be licenced, because licencing requires Canadian ownership and control (foreign investment restrictions). So “online undertakings” would “register” because most of them are foreign, and because Canadian streamers’ access to foreign investment is (so far) unrestricted.

Indeed, while it claims to “level the playing field”, my previous article showed how, even in that respect, Bill C-10’s likely outcomes are dubious.

Foreign services present a further conundrum

The Broadcasting Act asserts: “the Canadian broadcasting system… provides… a public service essential to the maintenance and enhancement of national identity and cultural sovereignty;”. It then lists over a dozen socio-cultural-economic objectives.

Under Bill C-10, the CRTC could selectively impose those domestic expectations on foreign streamers, based in foreign countries, operating under foreign laws, that have no business presence in Canada.

It’s an opportunity for lawyers with expertise in extraterritorial application of laws.

Bill C-10 risks significant collateral market damage

Basic economics tells us competition and new technologies expand consumer choice, exert downward pressure on costs and prices, and increase innovation and consumer welfare. The internet does all of that in unprecedented fashion, and Canadians are taking full advantage. Those outcomes should reduce the need for regulation, and make market intervention, where required, more focused.

Bill C-10 goes in the opposite direction.

Fixated on extracting Cancon obligations from a few foreign “web-giants”, Bill C-10 would vastly expand the Broadcasting Act beyond Canada’s borders into highly competitive, innovative markets. Foreign and Canadian video-enabled websites would have no idea — unless they employ avid readers of the Canada Gazette — whether regulations apply. Until, that is, they reach whatever criteria the CRTC sets for regulation, and find themselves hauled up before the regulator.

To scope the market, CRTC implementation proceedings would selectively require Canadian and foreign streamers — perhaps dozens — to register and file confidential information.

CRTC regulation isn’t quick or cheap. Proceedings are lengthy, multi-phase, quasi-judicial, adversarial, affairs. Lawyers, expert witnesses, interrogatories, filings, appeals, and regulatory fees, add-up — and the Minister expects 25% to 45% of Canadian revenues for Cancon. If you want exemption, you’d best be at the altar!

Yet, CRTC exemption is no redemption

To be sure, the vast majority of audio and video-enabled websites captured by Bill C-10 would have to be exempted from regulation.

But the CRTC uses exemption as a form of regulation. Rather than constrain that oxymoronic practice, Bill C-10 reinforces it with invasive information gathering powers. So exemption instead means ongoing uncertainty — for the millions unlikely ever to be regulated, and worse, for those who find themselves caught in the grey zone.

That’s cold comfort.

Audio and video-enabled websites would be well-advised to geo-block Canada. Bill C-10 would disincentivize foreign investment, potentially from some of the most innovative, creative global businesses.

Canadians would see their internet choice and freedoms greatly reduced. Costs would go up. Use of VPNs and piracy would flourish.

Ends don’t justify means

Again, engaging global online audio and video streamers in the production and presentation of Canadian content is a perfectly valid public policy objective.

Simply shoehorning them into new definitions under legislation that’s out-of-date even for legacy broadcasting is neither an efficient nor effective way to do it.

Since the 1951 Massey Report, the federal and provincial governments have managed very successfully to find ways to support Canadian content and artistic expression, in all media and disciplines, without resorting to such inapt and problematic measures.

My next article suggests an alternative.

Consultant Len St-Aubin concluded his most recent client commitment as of 31 Dec. 2020. The views expressed in this opinion are his alone. Formerly he was Director General, Telecommunications Policy, at Industry Canada, he was also a member of the policy teams that developed both the 1991 Broadcasting Act and the 1993 Telecommunications Act.

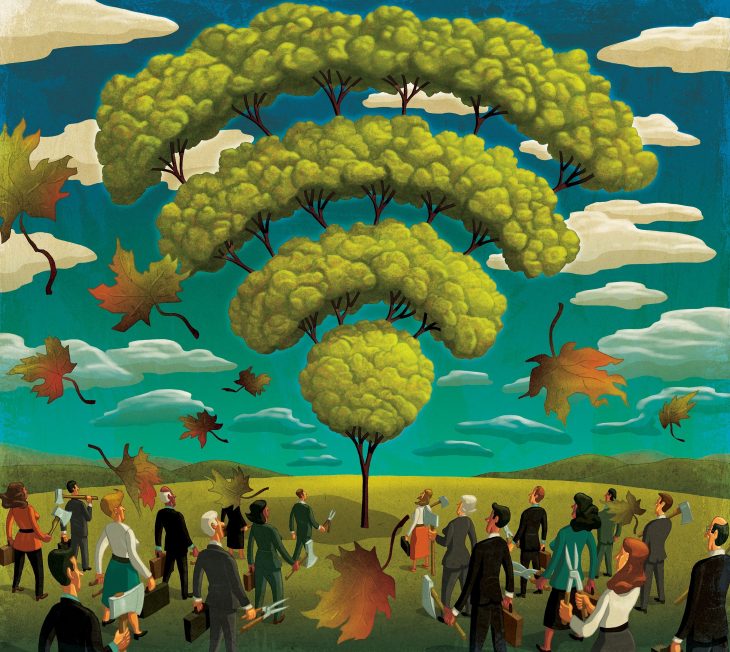

Original artwork by Paul Lachine, Chatham, Ont.