And is about to make the biggest financial mistake in its history

By Barry Kiefl

THE CRTC, APPOINTED BY THE government to safeguard our broadcasting system, in January completed a three-week long public hearing into how the CBC should be spending its $1.7 billion annual budget over the next decade, where CBC executives told the Commission they want to spend close to $400 million annually on internet services by 2022-23 and effectively reduce budgets of traditional radio/TV to accomplish this.

CBC radio already has a smaller budget than CBC digital.

The Commission’s decision on CBC’s licence renewals will be based mostly on unsourced hearsay and hype presented by CBC at the hearing and research reports authored by CBC. The Commission’s official notice for the hearing provides a link to these CBC reports and seems to accept their conclusions about audience behaviour without question. The reports rely on opaque public opinion surveys commissioned by the broadcaster that do not reveal the actual questions asked of survey respondents. Not the sort of evidence that should be used to make existential decisions.

Every CRTC CBC licence decision in the past 50 years has been based largely on how many Canadians use different CBC services and often led to important conditions of licence, for example, the decommercialization of CBC radio in the 1970s. In January’s hearing the Commission rarely, if ever, asked the Corporation questions about how many Canadians use CBC radio, TV or internet services or seriously discussed how audiences’ use of TV/radio is changing.

Audience response is the most important performance metric for a public broadcaster, but audiences were all but ignored by the CRTC at the hearing. The CBC unions did politely remind the Commission it’s own annual report showed traditional TV continues to be far more important than internet TV (Netflix, etc.) but the commissioners had no reaction. Historically, ratings data have provided critical evidence to support CRTC decisions but that seems to no longer be the case.

CBC, for its part, promised to be “audience-centric,” which is not the most precise statement. The Commission did not respond when CBC made boastful claims about its radio/TV/internet audiences in the first hour of the hearing and had no questions about these claims then or over the next three weeks.

For example, CBC claimed its news channel audience had almost tripled, that CBC Listen was up 50% and CBC was the number one Canadian online service. These claims were not questioned or explored by the CRTC. When CBC declared the audience has gone “digital,” the commissioners smiled pleasantly and allowed CBC managers to propose spending less money on traditional radio/TV services and more on digital services such as CBC Gem. The latter was mentioned dozens of times in the hearing; CBC claimed at the hearing the Gem audience was up 100%.

This claim is not explained and can’t be verified by independent ratings surveys—Numeris does not measure the CBC Gem audience unless it is a live simulcast of the linear CBC TV service and the audience is not reported separately but included in the total audience. Comscore provides only partial coverage of the Gem audience, excluding much of the viewing on TV sets. The only independent comprehensive survey data I am aware of shows that Gem has a very small audience (see below) .

CBC Gem is similar to Netflix in that it is streamed via the internet and one can watch programs on-demand. Both have been available in Canada since about 2010. The similarities end there. Gem, which changed its name in 2018 when it began to accumulate and heavily promote a number of foreign titles, is primarily a free service, whereas millions of Canadian households are willing to spend up to $20/month on Netflix.

CBC’s strategy appears to be to compete not only with Netflix but also Britbox and Acorn TV, two Brit-oriented streamers now available in Canada; during the hearing CBC managers even mistakenly claimed Gem aired Acorn’s most significant program (A Suitable Boy).

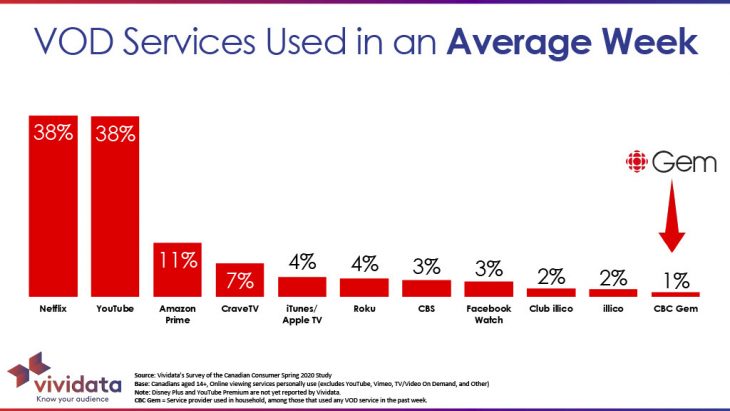

An independent survey commissioned in 2020 by IAB Canada shows almost 40% of Canadians use Netflix in an average week, while Gem, a free service, barely registers at 1% weekly audience reach (above). Another 2020 report, authored by CBC, and published by thinktv Canada reveals that after many years relatively few Canadians have bothered to download the CBC Gem app and its audience is equally sparse. The CBC was careful at the hearing to refer to the future, as yet unmeasured, potential audience for Gem.

“Anyone with a grain of curiosity would have asked how the CBC Gem audience is measured today.”

IAB Canada/thinktv are industry associations financed in part by CBC. The public broadcaster sits on their boards but these damning studies and other studies by thinktv that largely contradict CBC claims about radio/TV audience trends were not discussed at the hearing. The Commission didn’t even bother to ask how many people pay to receive the commercial-free version of Gem.

Anyone with a grain of curiosity would have asked how the CBC Gem audience is measured today and would have learned that it is effectively not measured by the regular ratings company. Thus, the CBC, CRTC and others know very little about the Gem audience, other than in the special studies above and notoriously unreliable “server” data.

CBC tries to silence all critics by touting the large monthly audience reach of CBC.ca, the large collection of CBC web sites, including CBC.ca, CBC Listen and CBC Gem. The source for this data is Comscore, which has measured web sites in Canada for many years. CRTC does not subscribe to Comscore data so it has to take CBC claims at face value.

During the hearing, CBC claimed some 24 million Canadians visit CBC web sites on a monthly basis, according to Comscore. This is commonly referred to as audience reach. When small audience services use ratings data, they usually focus on audience reach, which gives one the biggest audience number but can be very misleading.

In the mid-1990s, when web sites began using audience measurement, internet ratings companies pushed clients to use audience reach on a monthly rather than weekly or per program basis, so as to give the impression of a large audience. To be counted, a user need only tune in for a minute in a given month. CBC hasn’t changed and adheres to the 1990s approach.

The fact people spend little time with CBC.ca or how that time compares to time spent on Facebook, etc. was never discussed, nor was the fact that many of the 24 million users who sign in to CBC.ca do so to send an email to a program or “like” something CBC has aired on radio or TV. The digital audience is by its nature a return path for traditional radio/TV broadcasters.

The bottom line is while CBC.ca has a large monthly audience reach, the average visitor spends only a few minutes per week with the service, a small fraction of the time compared to what people spend with CBC radio/TV. This is unlikely to change given the competition on the internet from big technology companies.

CBC claimed at the hearing that the average visitor to CBC.ca spends 25 minutes per month on CBC’s sites, but failed to mention Canadians on average spend over 1,000 minutes a month with CBC radio/TV (although English TV has struggled to attract an audience of late). This radio/TV number is calculated using the CRTC’s own annual monitoring report.

In its last licence period CBC committed to spending only 5% of funding on digital services. That has since ballooned to roughly 20%. BBC meanwhile has capped digital expenditures at 10%, an amount more in keeping with the value and nature of the digital audience.

The CRTC has an obligation to CBC radio listeners and TV viewers to protect the budgets of the most important CBC services and not allow CBC managers to spend hundreds of millions of dollars chasing an imaginary audience.

Barry Kiefl is president of Canadian Media Research Inc., a company he established 20 years ago after a 25-year career in research at CBC.