Towards a Canadian strategy

OVER THE LAST two weeks, I’ve argued the Canadian strategy of supporting, and indeed actively pushing for, the vertical integration of our broadcasting system was a mistake, suggesting the vertically integrated companies – namely Bell, Shaw, Rogers and Quebecor – had not and will not become international distributors of content as it was presumed.

(Click here for part one and here for part two)

A reader pointed out it’s always easier to take the position of a critic – particularly in hindsight – so let’s look at the changes which have occurred and how we might approach a new strategy for the industry. This is a very complex problem and it is my belief that our core focus should be on developing our own new Canadian strategy.

The word strategy is, in my view, misused in much of the business literature so let me give it a more precise meaning. Strategy is about how we move forward. To have a complete and solid strategy you need to do three things:

- develop a clear diagnosis of the current challenges

- develop a guiding policy that addresses the obstacles called out in the diagnosis and

- create a set of coherent and feasible actions to carry out that guiding policy. [I credit the structure of this analysis to UCLA Professor Richard Rumelt in his excellent book, "Good Strategy, Bad Strategy"]

Diagnosis from the macro perspective

The starting point is to understand the two fundamental changes within the industry and their impact on the broadcasting system. It is axiomatic that the primary change has been the digitalization of content and the attendant spread of the Internet driven by improvements in computer processing power, data compression, bandwidth and data storage. These technologies emerged in the 1990s but have continued to spread and accelerate over the past decade. The impact has led to many changes in the Industry but I feel the most important are as follows:

Content: The content market is quickly changing from national to global. While content has always sought global markets through traditional distribution the difference now is the technological barriers have been breached making it easy to disseminate it across borders. The movement is clearly fastest in English speaking markets but is rapidly spreading across the globe. The primary driver of this change has been Netflix, which was the first to pursue a pure-play global distribution strategy.

Now, the major studios are following quickly, with Disney and CBS likely to be the first big movers but it’s certain that more will follow over the coming year and years. Other major players who already have output deals will seek the same sort of scale possibly by combining their efforts as evidenced by the BBC/ITV joint venture BritBox (which launched Wednesday in Canada). Scale is now about obtaining global reach, with original programming being the primary driver of longevity, as this will be the only programming that you can fully control in the long term.

The rise of global technology platforms: The major technology companies – namely Amazon, Apple and Alphabet (Google) have continued to push out their content platforms globally. Amazon appears to have an early lead with their Prime service now having more than 50% market penetration in the U.S. and close to that in other important territories like Germany and the U.K. Amazon and Apple are also making major investments in original programming. The traditional players in both content and delivery are responding but the tech companies have significant scale and an interest in playing the long game in the OTT space.

“Direct competition with these companies is likely impossible as their technology networks are so well developed they are potentially unassailable.”

One of the key challenges is these technology companies are not symmetrical competitively speaking (as in ‘competing in the same space’) but are asymmetrical as they are more adjacent to each other. They also compete very differently to the traditional providers who used bundled offerings combined with technological lock-in as their primary marketing and retention methods. The new technologies rely on network effects which capture attention differently and may in the long run prove to be more powerful. Direct competition with these companies is likely impossible as their technology networks are so well developed they are potentially unassailable.

Diagnosis from the micro perspective

Perhaps as important as the macro perspective are how these technological changes have impacted the individual or consumer level. They have changed consumer habits in a number of fundamental ways; the first of which is they allowed the consumer more control and more choice over their content offerings. This has resulted in more challenges for providers who must address the demands of a consumer who want a frictionless experience of content, when they want it and on the device of their choice.

The technological changes also open up a direct relationship between the content provider and the consumer. The traditional intermediaries have lost some of their control over the consumer with the development of social media and other digital marketing opportunities.

The impact on the Canadian system is now obvious. The primary strategy of our vertically integrated companies is intermediation of U.S. content. Canada spends more on U.S. programming than any other country in the world. However, this strategy only works so long as the Canadian importer can maintain a margin between their license fee and their sales to the consumer. This strategy worked when the technology required a domestic partner for delivery but will be much more challenging and harder to maintain in the long run as the consumer now has other options.

Also, as advertising dollars shift to digital it will be increasingly difficult to justify this model. What happens if the U.S. partners start selling direct to consumers themselves? What happens when they start selling their own advertising on those DTC platforms? What happens when other complimentary businesses prioritize the customer relationship over the traditional revenue streams? This is particularly true when the business model incorporates the acquisition and use of consumer data – such as with Netflix and Amazon.

However, maybe the bigger problem is Canadian content, or should we say Canadian identity?

The virtuous circle that creates Canadian content

The structure of the Canadian broadcasting system was really built around the import of foreign content. The broadcast licenses anticipate this, so as a condition for allowing it there is a corresponding obligation to spend money on Canadian programming. The bargain was clear – you can enjoy the benefits of audience and reach and in return you shall spend a designated portion of your revenue on Canadian content – known as Canadian Production Expenditures (“CPE”). This is the “virtuous circle” where the right to access the broadcasting system and to intermediate foreign content essentially floats the Canadian production system – or at least that portion not covered by the BDUs.

“When that gap narrows and revenue decreases – and when the competition from overseas faces no such expenditure – the system will collapse.”

Implicit in the concept of a CPE is that there will be a gap – perhaps a significant gap – between what is paid for the foreign programming – and the revenue. Therefore, paying a portion of it into the production system is feasible. However, when that gap narrows and revenue decreases – and when the competition from overseas faces no such expenditure – the system will collapse. It’s worth noting all Canadian broadcasters have sought relief from their CPE requirements over the past decade. Over the long term the revenue gap will continue to shrink and eventually the cycle will end. It is just a matter of time.

The structure of our system makes it particularly vulnerable because broadcasters need to be more competitive, which means they need to reduce their Canadian content requirements. This is creating a feedback loop that in many respects undermines the core reason for having a separate and different broadcasting system in the first place, which should be to tell our stories and develop our industry.

The consumer side of the Canadian system

Our broadcasting system has been one determined to maintain the illusion of scarcity in a time of abundance. The attempt to simplify it with “pick and pay” was really a half measure that has had little impact on consumer choice while causing a huge impact on the revenues of smaller networks. The reason is clearly that the vertically integrated companies’ (VIs) control of the wholesale market prevents the choices made by consumer from having a significant impact on the price they pay.

The new platforms – like Amazon’s Prime –give access to all content with pricing largely set by the content creator. This ease of choice and flexibility is not integrated into our broadcasting system, which results in higher friction with the consumer.

The divide between generations is the most visible evidence of the chasm between the past and the future. Those Canadians over 50 have held staunchly – some would say surprisingly so – to the traditional broadcasting system. However, those Canadians under 30 – raised in the digital world – have been far less eager to sign up. The main reason appears to be friction, but also includes economic concerns. In any event, the attachment the younger generation has to new technology does mean the system will be forced to adapt to their primary behaviours if it intends to survive in the long term.

Two conclusions from the diagnosis

1. The situation is dire. Our predominant strategy was about domestic scale but the industry has shifted to global scale. Our content creation strategy was supported by intermediation which will not be viable – at least as a primary strategy – in the long run.

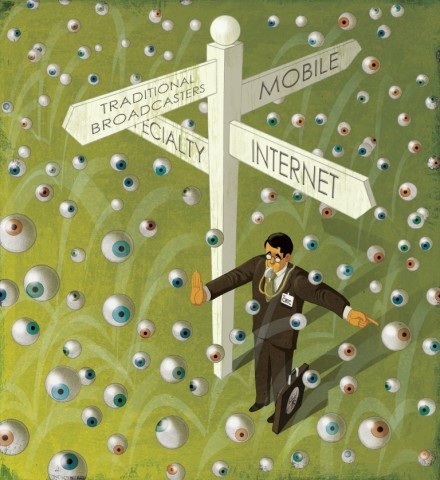

2. Consumers will be seeking content through all different types of online platforms. They require less friction and more flexibility in the content choices they are offered and how they pay for it.

Re-thinking priorities

Before we proceed to a new guiding policy we must better understand our priorities.

It is clear in the Broadcasting Act our system is intended to be a public good that seeks to ensure that Canada has a technologically current system that provides content and allows for creation of our own content to tell our own stories. We can maintain Canadian ownership for the technology side – at least of the Internet and mobile infrastructure. However, the content side is very troubled.

“There is really no point in supporting a system that does anything else.”

Our focus needs to be on how we re-configure the system to support the production of original Canadian programming that can hold its own in an international market. This is the area most in danger. Furthermore, there is really no point in supporting a system that does anything else. We may as well just remove foreign ownership regulations and hand the keys of our identity to the USA.

Scale and competition drives content strategy rethink

If we think only in terms of creating more content, it simplifies the task of coming up with a strategy. Execution may be another matter. The creation of content requires three things – creative personnel, financing and distribution. Finally, we need to consider if we have all three things, can we be competitive? Most of this I will detail in part four next week. However, there are two elements that are worth mentioning now.

When we considered scale at the time of vertical integration we did not ask the question – what kind of scale? It matters because each industry is different. Manufacturing often requires large corporations capable of making huge investments in infrastructure. This is also the case with our BDUs and their technological investments. However, it is not necessarily the same in respect to content production.

Creative industries do not necessarily require the same sort of fixed scale. The reason is that the creative process itself does not easily commoditize. Creativity does not stem from a mass manufacturing process but from the mind of one, two, or a few key creative people. This also means barriers to entry are lower. For example, Netflix and Amazon were quickly able to finance and produce award winning content.

This doesn’t mean that money is not important. Clearly production values improve with additional funding, but this financing must always be supported with distribution revenue. For Canadian producers, this ultimately means most of the revenue from the original programming must come from outside Canada. This has been the case with most television and film productions for decades now. Our goal with the broadcasting system should be to configure it to enable this process while at the same time giving broadcasters an incentive to produce more Canadian content.

Finally, we need to reconsider competition. Again, our strategy was to create powerful monopolies within Canada but that ultimately did not make us more competitive. We need to look at competition more carefully within the content market. Creative products keep our attention for relatively brief periods of time and when that time is over we’re ready for something new. This means competition is for some part of that attention – and how to monetize it.

If you consider the size of the global population – even the reachable and monetizable portion – and multiply that by the hours people devote to watching content – it’s huge. Even the biggest shows only hold a fraction of the audience’s attention – every high budget dramatic series can be binged (and often is) over one weekend. In fact, it is the largest single product market in the world, by a lot, and can only continue to grow. We must be part of it.

Huge markets support many players and it is possible to play in a market like this without going “head to head.” Think of all the songs on the top 40 – they all compete with each other but they also market each other as well. When you watch the Academy Awards, all of the films are in competition with each other but you will likely watch several of them because if they are nominated – they’re all winners. Once we stop looking at competition as a zero-sum game it starts to give us some new ideas on how we might be able to compete.

I will lay out all of this, along with some specific suggestions for what we might do to secure our broadcasting system for the future, in the final part of this series next week.

Brad Danks is the CEO of OUTtv and an adjunct Professor of Law at the University of Victoria