The big four have not become the content exporters they were supposed to

LAST WEEK, I RESPONDED to a Scotiabank report which said the success of Netflix in gaining subscribers, along with Google and Facebook’s dominance of the Canadian advertising market, meant a merger of Bell and Corus was a logical market response to ensure we remain competitive.

I question the strategy of further vertical integration in light of its obvious failure. My core argument is VI has failed because it did not properly take into account the competitive advantages of the vertically integrated companies. As their competitive advantages are in Canada alone and rooted in their control of the wholesale market in the broadcasting system, they were only competitive against Canadian competitors in the system. This is demonstrated by their dominance of the now highly concentrated Canadian broadcasting market. However, it made them no more competitive against foreign competition (in fact it is not clear they try to compete at all) and as such our system has overall been weakened by this strategy.

Here I want to talk about the rationale of the policies which support vertical integration: that the vertically integrated companies – specifically Bell, Rogers, Shaw and Quebecor (hereafter the “VIs”) – would become our international content distribution leaders, and why that is very unlikely. In part three, I’ll have suggestions for where we need to go next.

I also need to clarify two points thanks to some discussions I’ve had this week. The first is that I absolutely do not mean to suggest these companies intentionally misled the CRTC or anyone, or are somehow breaking promises. On the contrary, I simply assume that they are acting rationally, intelligently and doing what all corporations do: attempt to create value for themselves and their shareholders. This last part is crucial because as privately held corporations the law, particularly shareholder rights, does not allow them to act in any other way. My overall argument rests primarily on this assumption and on the fact successful companies create and follow competitive advantages. They play where they can win.

The second is when it comes to content I am focusing entirely on scripted and non-scripted entertainment content. My analysis does not include live sports or news. In fact, when it comes to live sports my opinion would be the opposite: that the VIs are in a better position than most companies to benefit from and utilize the enormous spillover effects of sports due to its highly national and local character. News is also different, as it has a similar national and local character. For a good discussion of this please see the excellent Final Report on the Canadian News Media published by the Standing Senate Committee on Transport and Communications in June 2006, that was rather prescient as we look back now.

Will the vertically integrated companies become content exporters?

The expectation that the VIs would become Canada’s content exporters was implied in the early decisions of vertical integration. The general argument at that time was that we need companies in Canada which have scale if we wanted them to compete on an international level. In the “Let’s Talk TV Decision” (Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2015-86) the Commission made this expectation explicit:

"Looking into the future of particular services and companies, the Commission expects that vertically integrated companies (companies that own or control programming services as well as distribution services), for their part, will continue to have the opportunity to leverage their resources and audience reach to acquire popular and lucrative programming as well as be well positioned to produce high-quality programming made by Canadians. Their critical mass provides these companies with the financial capital required to succeed both domestically and internationally."

It is clear the Commission had this expectation and that the rules were being changed to pave the way for this to happen. What also happened is what I would call the internalization of this policy – which became the guiding principle for all decisions. It impacted everything from the relationship between the VIs and producers as well as the decision to remove conditions of carriage for independent broadcasters.

The policy’s assumption was that producers would need to conform and independent broadcasters were going away anyway so we might as well hurry the process along – only the VIs could save us as they became significant exporters of Canadian content. However, for the reasons set out below, this hasn’t happened yet and is very unlikely to happen in the future.

Understanding complements

One of the most important concepts in all of business relates to the concept of a complement. Products and services are said to be complementary when each of them combine to increase the demand for the other. Economists call this “negative cross elasticity demand,” but most people know it as “ketchup to hotdogs” or “cars to gasoline”. From a business perspective, expansion into a complementary business can be a good strategy when the new business opportunity is aligned with the current operations and supported by overlapping scale or knowledge a company has gained from its current business activities – such as customer relationships or data.

The VIs grew over the past 50 years by developing very successful complementary businesses. Beginning as telephone or cable companies, they leveraged their infrastructure and customer relationships into Internet and mobile as well as becoming broadcasting distribution undertakings (“BDUs”). These businesses are highly complementary in all respects, from technology to infrastructure to marketing. The icing on the cake is that they are also protected by regulation from foreign competition. In business environments, it doesn’t get much better than this.

However, it’s not clear they have any complements with respect to the production and distribution of original content. Their conditions of license require them to produce or commission content, but this is an obligation and not necessarily an opportunity. U.S. Studios produce content for their domestic market but in most cases the content is also for export where it usually earns most of its revenue. However, it took decades to develop this business.

The emerging platforms such as Netflix, Amazon and Apple have also moved into original programming both to differentiate their product and to drive international growth strategies. Acquiring content is usually cheaper and always more certain than original production. In order to treat original production as an opportunity there needs to be a complementary business strategy – otherwise it is just a cost of doing business required by a broadcast license.

“This strategy makes sense when you have a high degree of control in the Canadian market but does not necessarily lead to exporting.”

The type of content the VIs make and how they structure most of their relationships is very telling about their perspective. Most of the original dramas are produced in partnership with other companies. The VIs license Canada and the partners finance and control the international rights as they have the relationships and infrastructure to exploit these rights. Many of the biggest programming investments in reality television are foreign formats such as shows like Amazing Race Canada, Big Brother Canada, MasterChef Canada, Chopped Canada, etc. The production of such programs is a good business model when your competitive advantage is national, but these programs do not export, as the format is localized in each country. Again, this strategy makes sense when you have a high degree of control in the Canadian market but does not necessarily lead to exporting.

Contrast this with foreign competitors where complements abound. It should be no surprise that Disney is the first studio aggressively to begin a new round of mergers in preparation for the coming content wars with Netflix and the technology giants – Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Google. Disney has theme parks and an enormous franchise and merchandising empire to exploit and protect. Other mergers are coming soon – CBS-Viacom may likely be the next – all in pursuit of a global content strategy to defend international channels, brands and other complementary businesses. This is the battle that is currently pushing these companies towards mergers and acquisitions.

The technology giants will also continue to expand into original content in the pursuit of complements to their core businesses. It must be remembered that Apple’s profit on their first US$10 billion in revenue from iTunes was said to be zero. However, they sold a whole lot of iPods. No one should be surprised if they acquire Netflix in the coming months to expand their position further.

Amazon is probably more interested in the customer relationship than being a pure content company. Google wants to expand their reach to increase their search business – and after Google, YouTube (Google-owned) is the number-two search platform in the world. Finally, Facebook wants to further expand its data acquisition and learn more about its users’ tastes, preferences and behavior. There is no better way to learn this than from the video content choices and viewing habits of their users.

It’s certainly true each of these companies bring an enormous amount of scale and resources, but they would not be investing into original content unless they had complementary business models. They might just as well build rockets like Elon Musk’s empire. Instead the complementary strategy allows them to spend on content and rationalize the expenses in more than one business unit. Apple buying Netflix would allow them to pursue international expansion and sell more technology products at the same time.

Dumb pipe paradox

The second reason for my belief the VIs will fail to become international distribution companies relates to their core businesses – their cable/satellite, Internet and mobile operations.

Conventional wisdom, until the early 2000s, held that cable and telcos should pursue content strategies simply because they could. However, Boston Consulting Group analyst Craig Moffett flipped this thinking on its head. His seminal 2006 paper, The Dumb Pipe Paradox, as summarized here, made the case clear:

"Leaving aside the technical aspects of the report, Moffett’s thesis was disarmingly simple. It rested on three assumptions. First, although cable revenue in a broadband-only world would decline, so would cable costs – a large, and growing, fraction (one-third) of pay TV revenue went toward acquiring content, but almost none of its broadband revenue did. (The cable company simply charged for access, and customers streamed whatever they wanted.) Second, capital expenditures were far lower for broadband than for pay TV: Broadband had no set-top boxes, network-based projects, or head-end servers (facilities that receive, process, and distribute television signals). As a result, invested capital could be put to work more efficiently. Third, there was room to further increase broadband prices, since in most parts of the country, cable operators remained the only providers of high-speed broadband. (Wireless and DSL providers presented competition in less than 30 percent of the nation.) And prices could be tailored to demand: If consumers using more bandwidth were charged more, revenue would increase still further.

These three arguments – lower costs of acquiring content, lower expenditures on capital, and the potential for price increases and price discrimination – led Moffett to a “dramatically counter-intuitive and starkly anti-consensus” conclusion: The economics of a dumb pipe scenario, he wrote, “are actually better than those of the business today."

– The Content Trap, Bharat Anand – page 57-58.

If we look at the overall revenues of Bell, Rogers and Quebecor, we see that Internet and mobile revenues dwarf those earned from media. Furthermore, the Internet and mobile businesses are protected by regulation whereas the content sector is not – and certainly cannot be – in the same way. This is probably why other BDUs – even including several very large companies such as Telus, Eastlink and Cogeco – have not entered the content space. Their current core business is much more profitable and much, much more certain.

“If shareholders of these companies were choosing between further mobile and Internet investments or content acquisitions, the choice would be clear. It’s not content.”

These core businesses are also going to require significant investments in new infrastructure to maintain consumer’s expectations in the decades ahead. If shareholders of these companies were choosing between further mobile and Internet investments or content acquisitions, the choice would be clear. It’s not content.

There is, of course the exception of Comcast in the United States, which acquired NBCUniversal, among other content assets. This may be the exception to the rule although NBCU is a global player in the content business and was well established at the time of acquisition with a history that even pre-dates the founding of Comcast itself. It may serve a model for Bell or Quebecor who may look for a global content acquisition – should such an opportunity exist. This would make more strategic sense than a Corus merger if the plan were to build an export strategy. However, it still requires a major shift in corporate focus.

Conversely, we may already be seeing signs that a few of the VIs understand this and are preparing to exit the original content market. The biggest of these moves is Shaw’s decision to sell their content assets to Corus. The Shaw family is on both sides of the deal and it makes sense going forward that Shaw protect its core business and Corus pursue a pure play content strategy.

Rogers has clearly slowed its content investment strategy. Its decision (with Shaw) to shut shomi, contrary to Industry gossip, was not because the service was failing – it was not – but because it did not contribute to a long-term strategy that Rogers wanted to support alone without Shaw. If Rogers’ plan was to move into international distribution shomi certainly would have been a good building block from which to begin the acquisition of premium content and international rights.

The main outlier, at least in English Canada, remains Bell, which appears to be continuing the practice of tying up U.S. content partnerships – most recently with a new deal with Starz (part of Randy Lennox’s “rich uncle” approach). Intermediating U.S. brands and content appears to remain the core content strategy. Corus still has the benefit of its Shaw family ownership within the Canadian market, but as Canada’s largest “pure play” company it has not yet begun to focus its energies beyond Canada in a significant way. So, is a merger in the making?

Obviously, this is all up to the companies themselves. Apart from the regulatory hurdles, it could be either good or bad for everyone else depending on how the regulators approach its approval. The health of these two companies is very important to our system but cannot be defended to the point of ending Canadian broadcasting. The risk is that a merger will not succeed and will only slow the decline until the merged company is forced to ask the Government to relax foreign ownership rules to bring in partners from outside Canada, which will ultimately be the end for the Canadian broadcasting system.

“This may be optimistic (naïve?) but at least, for the first time in a long time, we could focus on making the Canadian system functional for all stakeholders instead of just a few anointed companies.”

There is also the possibility that the merger could create the opportunity to end the policy of vertical integration and reinvigorate the system. The starting point would be to open up the wholesale market and allow independents and new Canadian entrants to thrive. It would also be a good opportunity to have both Bell and Corus part with a significant number of the “dead stick” channels they currently have collecting ‘rent’ on the broadcasting system. This may be optimistic (naïve?) but at least, for the first time in a long time, we could focus on making the Canadian system functional for all stakeholders instead of just a few anointed companies.

There are good strategies, bad strategies or you can have no strategy. By far the worst situation is a bad strategy because it tends to take up all energy and resources while at the same time making us complacent to other possibilities. Vertical integration was a bad strategy. It failed. It failed because it did not properly take into account the changes going on in the world and properly understand the competitive advantages of the VIs relative to these changes. It tried to maintain a system of scarcity in a world of digital abundance.

It’s time for a new Canadian strategy for broadcasting. In the next part I will discuss what that strategy should be and make some suggestions about how we might get there. I am well aware that some ideas will be poorly received and others need more thinking. However, the two things we most certainly lack right now are new, good ideas and time. The future is here and we better start dealing with it right now and on its terms.

More on that in part three next week.

Brad Danks is CEO of independent broadcaster OUTtv and an Adjunct Professor of Law at the University of Victoria.

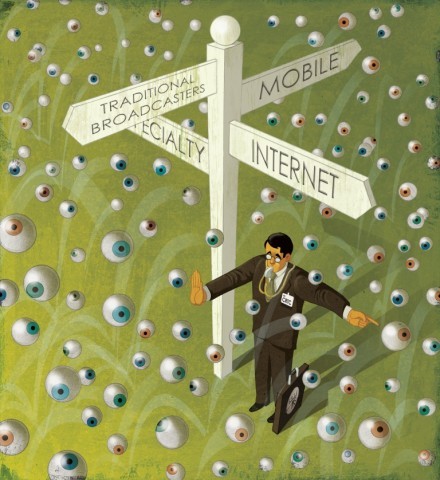

Illustration by Paul Lachine, Chatham, Ont.