Oh, and is it time for Bell Media and Corus to merge?

NETFLIX IS THE NUMBER one TV channel in Canada. Quibble with old definitions of an OTT and TV network if you like, but our big, linear networks are nowhere near as big anymore in the face of the global juggernaut that is Netflix. It’s been that way since last fall, and it’s not even close.

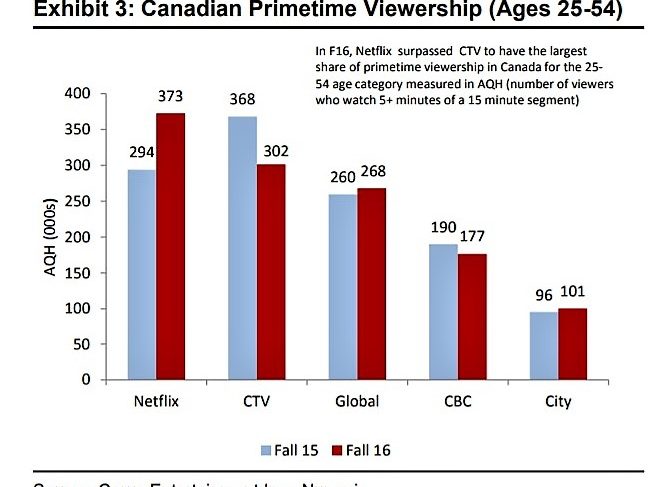

Who says this? Our largest pure-play media company: Corus Entertainment. In its December 1st submission to CRTC on the federal government’s call for comments on future distribution models, the company states on page three: “Netflix ranked number 1 in primetime viewing among Canada’s national television networks for adults 25-54 and millennials and has the highest AQH (average quarter hour persons) among kids. For the 18-34 (see chart at the bottom) and 2-11 demographics, the viewing data is startling in that Netflix’s share is two and half times higher than licensed broadcasters. This viewing data is particularly important as it demonstrates the level of fragmentation in the system and how quickly this has impacted the traditional linear market.”

(Ed note: To say nothing about the impact of the video offerings of YouTube, Facebook, Amazon and many others.)

To Scotia Capital financial analyst Jeff Fan, this means the way we assess the TV and media market in Canada is well overdue for a rethink – and if we’re going to have a strong industry here, regulators might have to let Bell Media and Corus Entertainment merge in order to fight.

While those two companies seem pretty big (and they are, in a Canadian sense), Fan pointed out in a note to investors this week that Google and Facebook already rake in over one third of all ad dollars in Canada now, larger than any other single medium. All of TV advertising in Canada pulls in just 23% of the available ad revenue in Canada, for example, adds Fan’s report.

While print has suffered most, Fan predicts that the bulk of the future shift in revenue will impact television – from both the ad and subscription sides. Audiences are attracted to the best content – and that can very often be found in the deep catalogues of Netflix and a growing Amazon, whose spending on content dwarfs the entire Canadian TV industry. Plus, new BDU and other technology is making it easier for consumers to move between platforms. Soon, surfing from Sportsnet to CHCH to Netflix, for example, will be as easy as changing a channel and viewers won’t care.

“Audiences are no longer differentiating their viewing between specialty TV, conventional TV, SVODs, or Advertising Video on Demand (like YouTube),” says Fan’s report. So, as more people spend more money on SVOD, AVOD and other transactional video services like iTunes, the impact on traditional linear services will only grow.

In fact, when the Scotia report combines the non-traditional or “digital” platforms, the Canadian video market starts to look vastly different than the industry governed by our existing regulations and laws – and Fan believes this should be reflected in new regulations for Canadian media companies and what they are permitted to do.

“The combination of digital subscription and digital advertising is approximately 25% of the market.” – Jeff Fan, Scotia Capital

“In subscription alone, we estimate SVOD accounts for over 40% of the market, and in advertising we estimate digital accounts for over 15%. The combination of digital subscription and digital advertising is approximately 25% of the market,” reads the report.

What all this means is that consolidation among traditional players will be necessary – and the only meaningful deal left in Canada is a combination of Bell Media and Corus. However, admits Fan, that will scare regulators, who would want to scuttle the deal or demand divestitures, because the two companies control so much of the traditional TV market. “We estimate that the (two companies') combined revenue share of the traditional TV market, including both advertising and subscription, is above 50% in 2017. If we were to include digital video, the combined revenue share is likely less than 40%, which, in our view, would be more conducive for a combination without divestitures,” he wrote.

In a little over two years from now though, as new digital players continue to rise and traditional TV continues to fall, it gets harder to make a case against such a consolidation. “Based on our estimate, the combined revenue share in 2020 will be approximately 35%, which is roughly in line with total digital video revenue share,” reads the report.

When it comes to share of viewership, which the CRTC has most often used to make merger decisions, Bell and Corus continue to dominate, taking about 70% of English Canada’s TV viewing share. However, with Netflix claiming the most-watched title, with Amazon, Facebook, YouTube and others gathering ever more eyeballs, does it make sense to enforce rules which only count traditional linear TV viewership? Essentially, as the industry and politicians struggle to update the Broadcasting Act, how then will the Regulator continue to define the TV market? It seems obvious the measurements and definitions must change, but when?

IF ONE LOOKS AT another set of data that came out this week, Deloitte’s Technology, Media and Telecommunications report, it points to a video market that has never been more fractured. While it sees no severe tipping point in TV viewing trends for the 18-24 year old set, traditional TV viewing is still “in structural decline” as other modes of viewing have risen to the fore.

Deloitte’s research points to a 5-to-15% annual decline in TV viewing among 18-24 year-olds in in Canada, the U.S. and the U.K. through until 2023, slowing after 2019, however.

“This is not what happened to other traditional media like newspapers, magazines and CDs with 18-24 year-olds where the decline went 5%, 20%, 80%.” – Duncan Stewart, Deloitte Canada

The good news is that it the company believes it is not going to zero, said director of TMT Research Duncan Stewart. “It’s not an exponential decline. There’s no tipping point. This is not what happened to other traditional media like newspapers, magazines and CDs with 18-24 year-olds where the decline went 5%, 20%, 80%,” he said in an interview.

However, while TV will still reach 90% or more of the population in the foreseeable future, the number of minutes watched is going to be drastically lower than what the industry long enjoyed, or even enjoys now. TV is still the “communal fire” around which we all still gather, Stewart added, noting live TV looks the strongest of the genres (when the 18-24 year old cohort does watch TV, they do 90% of it live, says his report), the fire just isn't as bright.

“The average Canadian 18-24 year old still watches about two hours of TV a day,” he noted. “I do not believe they’ll be watching two hours a day five years from now. Will they be watching zero? I don’t think so. I think it’s somewhere around an hour. I don’t have a lot of evidence or data for that… but when you say ‘do we need to watch five hours a day like we used to’? Probably not… I would predict by 2025, North American young people are still watching somewhere between 30 and 60 minutes a day of traditional TV.”

Given this data, how are we then to modernize the Broadcasting Act – the laws in which those 18-24 year-olds (and younger) will have to live with? Should we allow more consolidation so that a larger Canadian media company can better hold its own in face of all this change? What is broadcasting and what will it mean to younger people?

“It’s important to watch the habits of those who are the 18-24 year-olds of the future,” reads the Deloitte research. “In both the U.S. and U.K., their traditional TV viewing is declining as well, and often by annual percentages even worse than we have seen from current 18-24 year-olds.

“If the habits of this next generation persist over the next few years, our projections for stable or even less-severe declines could be wrong.”