BANFF – Canada has a long history of playing catch-up when it comes to setting policy for electronic media, starting with radio in the early part of last century and then with conventional television and cable TV through the 1950s, 60s and 70s. We can’t afford that any more.

The U.S. generally pushed the envelope in launching new media, Canadians adopted the technology and governments here played regulatory catch-up, often preferring early monopolies in radio or TV over competition in the marketplace.

“By first delaying the introduction of television, and then delaying the introduction of competing services, government policy almost guaranteed that, at the outset, and for quite a while afterwards, a lot of Canadian antennas would be pointed south – either actual antennas, or master antennas or head‐ends of cable systems that responded to the consumer demand for more choice,” said Kenneth Goldstein of Winnipeg’s Communications Management Inc., presenting a new paper to the Western Association of Broadcasters conference on June 9 in Banff.

Driven by enormous technological change, not to mention the pace of it, and keeping in mind our Minister of Heritage plans big changes for our laws governing Canadian content, Goldstein said we must come up with new “framing propositions to help guide us for the next five and 10 years, as the Canadian media industry makes important transitions in scope, technology, and business models.”

By 2025, he said, it’s likely that there will be few, if any, printed daily newspapers in Canada; there might be no local broadcast television stations (and both of those potential developments pose serious issues for the future of local journalism); we will still watch a lot of television, but the structure of the TV industry will look more like e‐commerce for programs; it will be even more important to give Canadians the tools to produce and to discover Canadian content; radio may still fit within the concept of broadcasting and in some communities, hyper‐local radio linked to highly‐focused local online services might become a new hybrid answer to local media; and the Internet will have become even more ubiquitous than today.

With all of these impending changes (driven, really, by global forces), the challenges they represent and the fear they induce, we must make sure we measure accurately what we are and where we are in the world in order to diagnose problems and develop effective policies and to “resist the urge to make policy based on myths,” he said.

The most troublesome myth, he said, is that Canada suffers from media concentration.

To Goldstein, “the ‘concentration’ idea has become a convenient scapegoat, to be blamed for the current economic headwinds being faced by traditional media, and, in particular, by newspapers and conventional television,” he said.

“There is no evidence that the corporate structure of the media industry is to blame for current downturns.” – Kenneth Goldstein, CMI

“It may be easier to come up with a scapegoat than to deal with more complex questions of technology and economics, but there is no evidence that the corporate structure of the media industry is to blame for current downturns for either newspapers or conventional television.”

Looking at the newspaper business, for example, Goldstein reminded delegates that the real culprit for that industry’s decline is the sheer collapse of classified ad revenue as sellers of used cars and sofas fled to free, online portals. Over $700 million in classified ad revenue has disappeared since 2005 in Canada, he said.

As well, when it comes to claims of concentration of media ownership, it’s a myth to say the Canadian market is concentrated, he explained, because most measurements don’t account for what he calls the “relevant market.”

“Here is a definition of ‘relevant market’ put out by the European Union,” Goldstein said. “A relevant product market comprises all those products and/or services which are regarded as interchangeable or substitutable by the consumer, by reason of the products' characteristics, their prices and their intended use,” he said.

“You will note that the consumer is at the centre of this definition.”

The EU also says: “The concept of 'relevant market' is different from other definitions of market often used in other contexts. For instance, companies often use the term 'market' to refer to the area where it sells its products or to refer broadly to the industry or sector where it belongs.”

He continued: “Let me give you an example. Let’s say you want to measure the retail market in a small prairie city. So you set out to find all of the information on the stores located within the city limits. The stores located within the city limits might be one definition of a market. But is it the relevant market? Well, no, it isn’t, if you left out the Wal‐Mart and Canadian Tire located two kilometers outside the city limits in a neighbouring rural municipality, because consumers will shop there as well as within the city limits.”

This is a bang-on parallel when it comes to the TV market, too, he added. “The claims that the television market in Canada is ‘concentrated’ are based on an incorrect definition of the relevant market – except that the players that have been excluded are not just Wal‐Mart; they are also Netflix and Google and Apple and Amazon and others.”

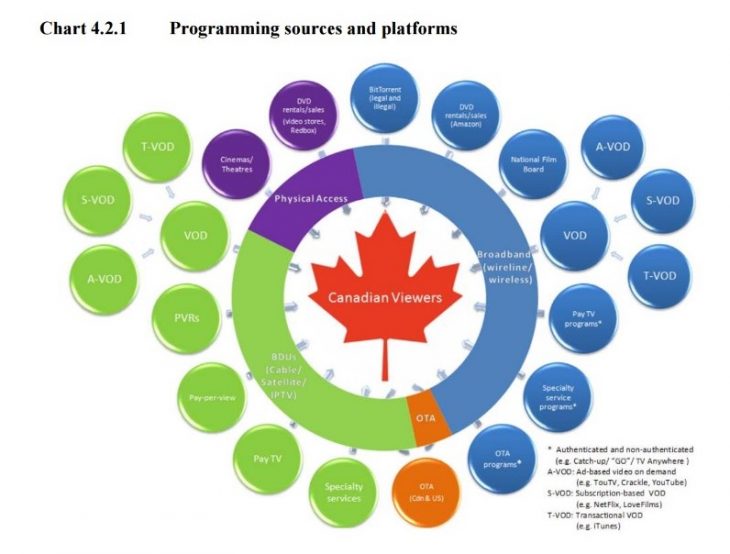

Even the CRTC’s Communications Monitoring Report, shows a large relevant market where Canadians have massive choice when it comes to video content. “Canadians enjoy multiple sources and means of accessing content, from conventional over‐the‐air linear broadcasting to digital media provided over the Internet,” reads the CMR, said Goldstein’s paper.

Those who claim the market is concentrated here only use data for slices of the market and not the entire relevant market, he said. “Obviously, if you leave out the time or money that Canadians spend on Netflix, on non‐Canadian specialty services, on YouTube, and on other television/video services, you will produce an artificially small market total, and the percentages for those players captured in that truncated market will appear artificially high.

“If you use the artificially‐truncated market definition, for which we do know the numbers, the total revenue in 2014 was $7.35 billion, and the largest Canadian player had a market share of 31.5%,” he said. “If you use the real relevant market, based on the CRTC’s diagram (see above, and below and linked here), the total revenue in 2014 was at least $10.4 billion, and the largest Canadian player had a market share of just over 20%.

“It’s clear that, if you define the relevant market properly, as the CRTC’s diagram has done, the Canadian television market is not concentrated.”